|

FEATURES

The China Critic - A Chronology | China Heritage Quarterly

The China Critic: A Chronology

William Sima

Australian Centre on China in the World

William Sima, whose research into the history and contents of The China Critic led to this combined issue of China Heritage Quarterly, has created a Chronology of the weekly. It follows the progress of The Critic from its first appearance in May 1928 through the highs and lows of the 'Nanjing Decade', and then through its various wartime permutations.

Will's Chronology, which is arranged by year below, accounts for the changing fate, and the friable editorial stance, of The Critic. It also provides numerous links to the articles under discussion allowing for them to be appreciated in an historical context.—The Editor

1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1945

Introducing a Chronology of The Critic

William Sima

In the following Chronology I attempt to breathe life back into The China Critic (published 1928-1940, 1945) by highlighting and re-presenting what I take to be the most momentous and representative content of this magazine. Complete 'objectivity' would demand the inclusion of all of the Editorials, Special Articles, columns, news items,cartoons and other features that were ever published in its pages—impractical if not impossible for a magazine that ran weekly for almost fourteen years. But the task is made easier with hindsight, as we appreciate the importance of the era in which The Critic flourished, since termed the 'Nanjing Decade' 南京十年 (1927-1937), and more recently described in theoretical terms as one of outwardly-engaged 'cosmopolitanism'.

This time (as well as the place, Shanghai) was in many ways the swan song of an era captured in the title of Frank Dikötter's 2009 book, The Age of Openness: China before Mao. In deciding which articles to include in this Chronology, I was also guided by the purposeful and conscientious words of The Critic's editors and contributing writers themselves, who were well aware that theirs was an 'age of openness'. On a number of occasions they articulated the endeavours of their magazine with great clarity and purpose. Christopher Rea, who contends in his editorial to this issue of China Heritage Quarterly that The China Critic practiced a kind of 'New Sinology 後漢學 before the fact', emphasizes the acute awareness of its contributors that they were forging a new understanding of China and its place in the world—as well as their engagement with Sinology approaches, such as it was in the 1930s.

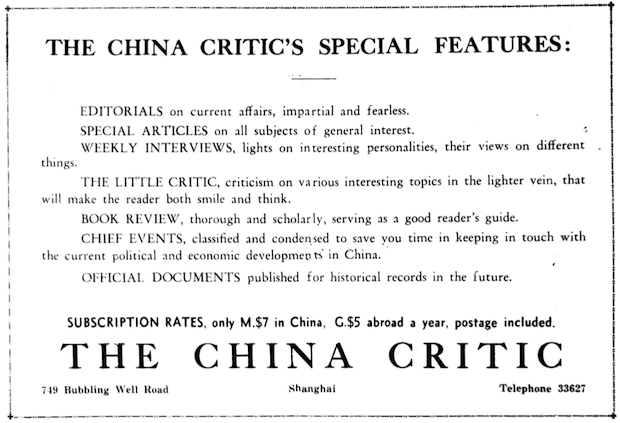

Fig. 1 The China Critic's Special Features, from the index supplement to vol.15, October-December 1936

There was no question about whether to include, for example, the 18 November 1937 Editorial 'The Book Street of Shanghai'—accessible in downloadable PDF, as is all material included in this Chronology, by clicking on the underlined link to the article. It describes violent interruptions at Fuzhou Road 福州路, then and still today the centre of Shanghai's publishing industry and a popular haunt for booklovers, as Japanese forces rolled through the city. Bookstores were forced to close their doors and some magazines were amalgamated to save on paper and printing costs. This editorial represents the era, its enthusiasms, hopes and thirst for knowledge writ large, partly because it fails to foreshadow its own demise; the writer's optimism about the future of the Shanghai publishing scene seems naïve only in hindsight:

All these are clear indications that the spiritual hunger of the Chinese is demanding ample reading fare. Such are the activities of the Book Street of Shanghai and we have reason to believe that the end of local hostilities will not curtail them.

Unfortunately, escalating hostilities would eventually curtail the publishing life of The China Critic. Exactly one year after this editorial was printed, the contributing writer George S.S. Kao described the war with Japan as being 'the gravest crisis in Chinese history' (see 'Japan Slams China's "Open Door"', 17 November 1938). On that Thursday, the war against the Japanese empire had been raging for 498 days. In precisely two more years The China Critic, by then a shadow of its former self—the final issue of 7 November 1940 was just eleven pages long, a third of its average size in the mid-thirties—would cease publication. It reappeared in 1945 but lasted four months.

In his editorial to the present issue of China Heritage Quarterly, Geremie Barmé speaks of 'China's unfinished twentieth century' to describe the explosion of unfinished possibility that Republican China has bequeathed to the twenty-first century. A plethora of issues debated then, from the nature and place of liberalism in China, to the role of education and need to improve civic consciousness, are still hotly contested—unfinished or unresolved—problems in the broader Chinese world today.

T.K. Chuan's 全增嘏 description of the spoiled young 'Chinese Brahmin', who contemptibly screams chu lo 豬玀 'pig' at his rickshaw coolie before heading home to '[write] a learned dissertation on the Standard of Living of the Rickshaw Coolies in Shanghai', (see 'Who are the True Chinese?', 20 July 1933) might be compared to today's fu er dai 富二代 ('rich second generation'), or to the more extreme instance of Li Qiming 李啓銘, of Wo ba shi Li Gang! 我爸是李剛! ('My Dad is Li Gang') notoriety (for details, see China Story Yearbook 2012, Red Rising, Red Eclipse at: www.thechinastory.org). Like their predecessors, Chinese students face the same difficulties in finding satisfying employment after graduation (see 'Complaints of a College Graduate, February 1935), and are still subject to uninspired rote-learning ('The Need for Education Reform', November 1945). Pearl Buck's 'New Patriotism' essays (of June 1931 and October 1933) advocate a patriotic spirit of unabashed admittance of China's problems and compassion for the poor, while deploring face-saving denial and crass jingoism: they could have been written yesterday, and should still be read today. And, as Leon Rocha points out in his contribution to this issue of the Quarterly, the thinking of Quentin Pan 潘光旦, China's most famous eugenicist and The China Critic's stalwart book reviewer, has been recently evoked as a 'verification for and precedence to Hu Jintao's 胡錦濤 political ideology'. While our social and political surroundings have changed immeasurably, these are just a few examples of how The China Critic speaks to us as if it were a contemporary publication.

In compiling this Chronology I have also endeavored to showcase the different sections of the magazine, and to indicate how these changed over time (Fig.1 shows The China Critic's features such as they were in the second half of 1936). I have highlighted a number of 'Special Issues', which focused on a contemporary topic for the week, as they show to us what this magazine's editors saw to the be the most pressing issues of their time. Altercations between the magazine's contributors and their readers—see, for example, Madame Sun Yat-sen's 宋慶齡 castigation of The China Critic group in November 1932, and the debate between Lin Yutang 林語堂 andthe French writer Maurice Dekobra in December 1933 and January 1934—provide a taste for how The China Critic was read, as well as how it was written.

All illustrations included in this Chronology are contemporaneous with the year to which they are attached. These include advertisements, cartoons, publication announcements and even train schedules, and they offer a visual dimension to readers who are interested in gaining a better sense of its fourteen years in print. In 1929, the business manager P.K. Chu's 朱少屏 'Subscription by Wire' announcement, and a 'China Critic Society Announcement' 中國評論週報啓事, allow us to imagine that The China Critic was read not only by men and women in cafés, but also by high school students in chalky classrooms. The enthusiastic embrace of the modern and of urbane leisure is evident in a number of elaborate advertisements, the Capstan brand of cigarettes not least among them. While today's Harmony brand 和諧號bullet trains can transport us from Shanghai to Hangzhou in forty-five minutes, or from Wuhan to Guangzhou in five hours, it is still diverting to imagine a trip from Shanghai down the Yangtze to 'Visit Progressive Szechuen' (see advertisement from February 1937) by steam boat.

1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1945

|