|

||||||||

|

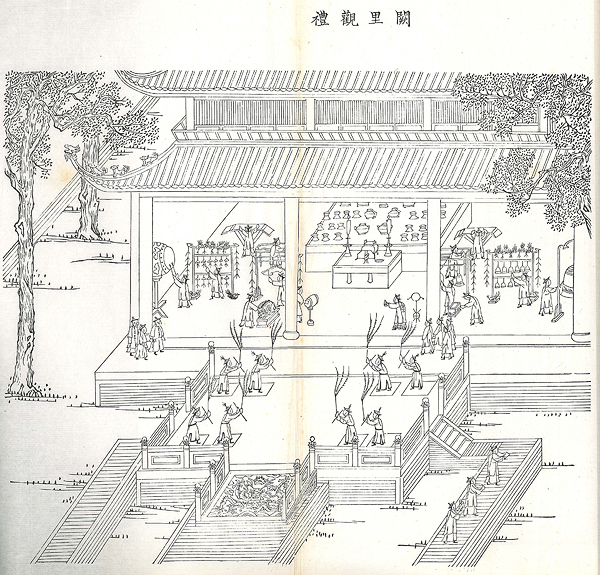

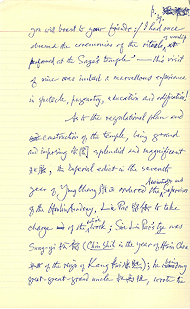

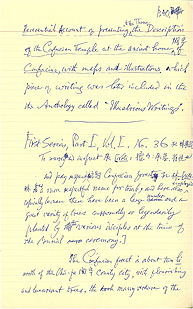

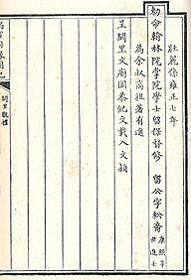

NEW SCHOLARSHIPObserving the Rites at the Ancient Abode of ConfuciusTracks in the Snow, Episode 35[1]Linqing, translated and annotated by Yang Tsung-han. Edited by John Minford with Rachel MayThis brief extract is from the beautifully illustrated autobiographical memoir Tracks in the Snow (Hongxue yinyuan tuji 鴻雪姻緣圖記), by the Manchu Bannerman author Wanggiyan Linqing 完顏麟慶 (1791-1846). It forms part of a newly initiated ANU research project devoted to the Bannerman culture of the early nineteenth century, under John Minford and Geremie R. Barmé and funded in part by the Australian Research Council. Other texts at the centre of that project are the Anthology of Bannerman Verse (Xichao yasong ji 熈朝雅頌集 ) by Tiebao 鐵保 (1752-1824), the Bannerman Prose Anthology (Baqi wenjing 八旗文經) of Sheng Yu 盛昱 (1850-1900) and the Snow Bridge Poetry Talks (Xueqiao shihua 雪橋詩話) of Yang Zhongxi 楊鍾羲 (1865-1940). This translation has been edited by Rachel May and John Minford from the original manuscript draft of Professor Yang Tsung-han 楊 宗翰 (1901-1992), done while he was an Honorary Fellow at the Research Centre for Translation of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, between 1985 and 1990. We include here reproductions of the manuscript pages from Professor Yang's draft, as well as the original text by Linqing, with accompanying illustration. Professor Yang was himself a Mongol Bannerman, son of the prominent Mongol Bannerman statesman and bibliophile Enhua 恩華 (1879-1954). Born in 1901, he first studied at Tsinghua University, and went to Harvard in 1921 to study Political Science. After graduation, he returned to Beijing, where he held various academic posts, including that of Head of the Department of Foreign Languages at Peking Normal University. Later he taught at Sichuan University, where he was Dean of the Faculty of Arts. After the Second World War he worked in the Chinese Embassy in Athens, moving to Hong Kong in the early 1950s. Yang's family background made him the ideal translator of Tracks in the Snow, and the editors have wherever possible preserved his impromptu and sometimes irascible comments. See especially Footnote 11! Other edited extracts from Professor Yang's draft translation have appeared in East Asian History 6 (December 1993), pp.105-142, and in Renditions 51 (Spring 1999), pp.29-65. The Confucian Temple 文廟 in Confucius' ancient abode 闕里 is a mere three days' journey from Tai'an 泰安 Prefecture. On the day dingchou, the first day of the eighth month of the year bingzi (AD 1816), being the legal date of the autumnal ceremony, I desired to be present and to observe the rites. I invited a staff member,[2] Zhou Jianting 周簡亭,[3] to accompany me, since he was a friend of the Ducal Office secretary Ye Rongpu 葉蓉圃 [4]. We started the journey on the day guichou, the twenty seventh day of the seventh month and reached the Qufu Guest House 曲阜客舍 on the day yihai, the twenty-ninth day of the seventh month. On the following day bingzi, after the appropriate ablutions and change of apparel, we entered the Temple and proceed to the Dacheng Hall 大成殿 to do obeisance to the Sage.[5] Then Mr. Ye came out and invited us to ascend the steps and to enter the Hall and gaze upon the Sage's effigy. We learned after enquiry that the image was made by the order of the local administrator Li Ting 李珽 in the third year of the Xinghe reign of the Eastern Toba Wei 東魏 dynasty (AD 542). I saw also the three ancient bronze vessels decorated with animal designs 犧象, and with cloud-and-thunder 雲雷 ornamental stereotyped designs. These were donated to the Temple by the Emperor Zhang 章帝 of the Later Han dynasty when he came in person to worship the Sage in the second year of his reign (AD 11); then, the northern gateway being opened, we went on through the Palace Commemorating the Sage's Life, where we surveyed the pictures and carvings on stone depicting events and teachings from the Sage's life. Among these was a picture of Confucius followed by his disciple Yanzi 顏子[6]; this particular picture according to legend was first made by Zigong 子貢, another renowned disciple of Confucius. A later replica was made by Gu Hutou 顧虎頭 of the Jin 晉 dynasty.[7]  Woodblock illustration for 'Observing the Rites at the Ancient Abode of Confucius', from Linqing's Tracks in the Snow Then we returned to the front of the Palace to read the calligraphy of the two characters 'Apricot Terrace' 杏壇 in ancient seal script by Dang Huaiying 黨懷英,[8] and the Encomium on the Chinese Juniper 檜樹贊 [9] written by the renowned Mi Fu 米芾.[10] We walked to the left of the Gate to see the Juniper tree planted by the Sage, before coming out from the Dacheng Gate 大成門 and reverentially reading the various stone monuments erected by the successive Emperors of the present reigning dynasty, who had all come in person to pay homage to the Sage. We next went to the Kui Wen Tower 奎文閣 and saw that the persons on duty were about to display the various sacrificial vessels and the musical instruments, which would be played as accompaniment for the sacrificial ceremonies of worship. They were also marking out the rows for the ceremonial dances. It was still too early for rehearsals. After this we went out and through the Tongwen Gate 同文門 to read all the stone monuments and tablets and steles erected in the successive Han, Wei, Song, Jin, Yuan and Ming dynasties. Finally we returned to the Kuiwen Tower to watch and observe the Yansheng Duke as he led the junior members of his family, together with the various officials on duty, to rehearse their steps—an impressive and elaborate ritual of ninefold offerings, and an imposing musical and choreographic display with eight rows of eight dancers. It was a spectacle both venerable and ancient in tradition, both reverential and harmonious in feeling, both awesome and inspiring in its effect. I was deeply touched, and lingered awhile, reluctant to leave the precinct. After this, I adjusted my apparel once more and ascending the Shili Tang 詩禮堂, the Hall of Poetry and Rites, I approached the old well of the Kong family. Thence I ascended the Jinsi Tang 金絲堂, where I enquired after the relic of the former site of Prince Lu's palace wall.[12] I was favoured with the privilege of seeing the costumes of all the successive dynasties in the unique collection of the Kong family. The Chief Administrator of the County 大令 Jiang Baisheng 蔣伯生,[13] wrote me a complimentary poem in which he said among other things: 'I can foresee that on your return to the Court in the Capital, you will boast to your friends: "I once observed the Rites of Worship performed at the Sage's temple".' This visit of mine was indeed a marvellous experience! As to the regulations and plans for the construction of the temple itself, which were indeed both grand and imposing, both splendid and magnificent, an Imperial Edict of the seventh year of the Yongzheng 雍正 Emperor ordered the Administrator and Supervisor of the Hanlin Academy, Liubao 留保, to take charge of the entire project.[15] Liu, who was my great-great-grand uncle 叔高祖, wrote a Reverential Descriptive Account presented to the Throne of the Confucian Temple at the ancient home of Confucius, with maps and illustrations. This work was later included in the anthology Illustrious Writings of the Age (Wenying 文穎).[15]

Yang Tsung-han's manuscript translation of 'Observing the Rites at the Ancient Abode of Confucius' with notes Notes:Yang Tsung-han's annotations are marked 'YTH', while those of Linqing are indicated by 'LQ'. The last word belongs to 'JM', or John Minford. [1] YTH: Yan Shigu 顏師古 (581-645) in his annotation of the Han History 漢書 of Ban Gu 班固 (32-92) maintained that 闕里 [queli] as Confucius' abode—里 in classical texts means house, abode, habitation; cf 左傳,哀公元年:里而栽. Liu Bao'nan 劉寶楠 (1791-1855) also annotated 闕里 as 闕黨 in his edition of The Analects 論語, adding: '孔子所居'. [2] LQ: from the Tai'an Prefectural Yamen. [3] LQ: Name Weirang 維讓, a native of Jiangsu. [4] LQ: a native of Jiangsu, and an Academy Student. YTH: this 'ducal' refers to the so-called 'direct lineal descendant of Confucius', who had been invested with the hereditary status of a peerage since the Han 漢 dynasty as Bocheng Marquis, then in the Zhou dynasty of the Yuwen 宇文 family it was elevated to Duke; and in the beginning of the Tang dynasty, it was demoted back to the status of Marquis. Subsequently it was restored to a dukedom in the days of Xuanzong 玄宗 and also given the title of Yansheng 衍聖. From then on, the hereditary title 衍聖公 was kept until 1935, when the Nationalist Government of the Republic ordained that the legitimate lineal descendant of Confucius should be invested in perpetuity as Hereditary State Officer in Charge of the Worship of Confucius 奉祀官, with the rank of 'specially appointed officer' 特任官. The hereditary peerage of 衍聖公 was thenceforth abolished. [5] YTH: Dacheng Hall being the legal title of the Main Hall in the Temple. [6] YTH: Yan Hui 顏回. [7] YTH: our author gives the pet name of one of the greatest painters in Chinese history: his more formal name is Gu Kaizhi 顧愷之, and his biographical sketch is given in the Jin History 晉書 and in various works on Chinese Art. [8] YTH: one of the small number of talented writers, poets and calligraphers in ancient scripts of the Jurchen Jin 金 dynasty. [9] YTH: R.H. Mathews' translation; I rather think it is fir or pine. [10] YTH: 芾 should be pronounced fu, not fei, because 芾 is the variant and simplified form of 韍 which is pr. fu, and is not the same word as the 蔽芾甘棠 in 詩經, which is pr. fei. [11] YTH: the rows of dancers started with two and culminated with eight. Only a Sovereign ruler, i.e. the Emperor, could employ the most imposing form, e.g., the feudal ruler of Qi 齊 or Lu 魯 could only employ six and that was the reason why Confucius exclaimed: 八佾舞於庭是可忍也孰不可忍也 in his condemnation of 秀氏 in 論語. So here Confucius himself has been honoured with the veneration paid to an emperor! [12] YTH: the wall of the palace of Prince of Lu where old classics were hidden during the days of Qinshi Huangdi. Later in the Han dynasty they were accidentally discovered during the renovation of the palace. [13] LQ: name Yinpei 因培, a native of Jiangsu, a specially recommended student from the Provincial Academy 貢生. YTH: R.H. Mathews translated this as 'senior licentiate'. [14] LQ: Sire Liubao's zi was Songyi 松裔. He was a jinshi of the year xinchou of the reign of the Emperor Kangxi [1721]. JM: Liubao, a grandson of the great Manchu translator Asitan 阿什但 (d. 1683), was Junior Vice-President of the Board of Civil Office from 1740 to 1743. [15] JM: 皇清文穎, an anthology of court literature edited by Dong Bangda 董邦達(1699-1769) and published in 1747. |

-small.jpg)