|

||||||||

|

NEW SCHOLARSHIPLingering Traces: In Search of China's Old LibrariesWei Li 韋力Introduced and translated by Duncan Campbell

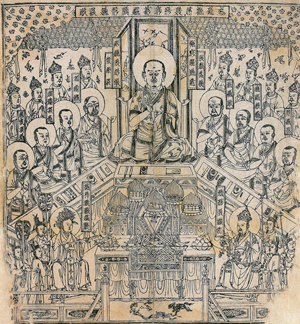

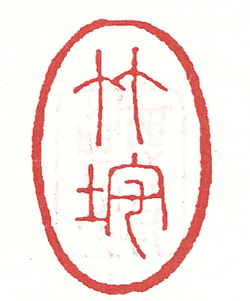

Fig. 1 An illustration of the translation of the sutras, found attached to a Tangut script version of the Xianzai xianjie qian fo mingjing 現在賢劫千佛名經, dated 1068-85. From Bastions of Civilization: A History and Exploration of Ancient Book Conservation [Wenming de shouwang: guji baohu de lishi yu tansuo 文明的守望:古籍保護的歷史輿探索], Beijing: Beijing Tushuguan Chubanshe, 2006, p.100. Wei Li 韋力 (b.1964), a native of Tianjin, is both a noted contemporary private Chinese book collector and an author of considerable eloquence. An inveterate collector of things from an early age, including grain ration coupons (liangpiao 粮票), his interest in book collecting was quickened in 1981 when he read in the paper an account of a book-buying excursion to Hong Kong made in the 1950s by the bibliophile Zheng Zhenduo 鄭振鐸 (1898-1958). As the result of years of painstaking effort, Wei Li's own library in Beijing, the Studio of the Angelica and the Orchid (Zhilanzhai 芷蘭齋),[1] now comprises more than 8000 titles in 70,000 fascicles and contains examples of imprints and manuscripts dating from the Tang dynasty onwards. Wei Li is wary of easy rationalizations of his motivations; he collects books, as his name card reads, because he is a 'Book Lover' (cangshu aihaozhe 藏書愛好者) and he is fond of citing a line much used over the centuries but which derives from Zhang Yanyuan's 張彥遠 (ca. 815-after 875) Record of Famous Paintings Down Through the Ages (Lidai minghua ji 歷代名畫記) to the effect that: 'Without engaging in useless pursuits how ever is one to discharge this life of limitation?' (Bu zuo wuyi zhi shi, he yi qian you yai zhi sheng 不做無益之事何以遣有涯之生). At the same time, although he has never sold a book that he has added to his collection, he is modest in his long-term aspirations as a bibliophile. The legend of his collector's seal, for instance, reads not 'Keep Hold of this Book Forevermore' or some such, but rather 'This Book Was Once to be Found in Wei Li's Home' (Ceng zai Wei Li jia 曾在韋力家). 'I am no more than a Library Clerk' (Diancangli 典藏吏), he says of himself, 'just another link in that chain whereby books are handed down through the ages'. In this respect, he explicitly disassociates himself with the more proximate, post-1949, traditions of book collecting that Zheng Zhenduo is perhaps most representative of—the 'Red Brigade' (Hongse cangshujia 紅色藏書家)—and seeks rather to re-establish a connection with the mainstream pre-1919 tradition; to him the book is an object of preservation rather than of criticism.  Fig. 2 The legend of this Collector's Seal, that of Qi Chenghan (1563-1628), reads: 'A treasure to be passed on through the generations by my sons and grandsons.' From Lin Shenqing 林申清, ed., Seals of Famous Book Collectors of the Ming and Qing Dynasties [Ming Qing zhuming cangshujia cangshuyin 明清著名藏書家藏書印], Beijing: Beijing Tushuguan Chubanshe, 2000, p.44. As an author (and executive editor now of the journal Book Collector [Cangshujia 藏書家]), Wei Li seeks to disseminate some of the immense knowledge of books and publishing that he has so painstakingly and incrementally acquired over the past twenty years. His particular research interests are focused on such areas as stele inscriptions, the history of East-West print cultural exchange, bibliographical aspects of the classical exegesis of the Qing dynasty, moveable type, the study of annotated critical editions, and research into catalogues of collector's seals. Of critical and abiding interest is his engagement, as he works on the catalogue to his own library, in that traditional form of bibliographical note, the Tiba 題跋 or, more recently, Shuhua 書話, that once served to underpin all scholarship in China. As well as being obsessed with the book as a material object, however, in recent years Wei Li has also become increasingly concerned with the traditional physical context of the book and its preservation and circulation—the 'Cangshulou' 藏書樓—and the fast disappearing remains of these institutions. In his book Lingering Traces: A Search for China's Old Libraries, sections from which are translated below, Wei Li sets out to find some of the remains of these libraries in the hope both of reminding people of their cultural importance and of alerting everyone to the need to preserve (indeed, restore) these sites. His is a compelling but elegiac voice. Wei Li's book is divided into eleven sections, detailing the author's excursions to Zhejiang, Changshu, Yangzhou, Zhenjiang, Suzhou, Ningbo, Nanjing, Hunan, Guangdong, and Shandong in search of remains of the old private libraries. For present purposes, I have translated both Wei Li's 'Introduction' (Yuanqi 緣起) to the book and a sample of the entries from his trip to Changshu, a region with strong and particular traditions of book collecting, as captured, most famously, in Sun Congtian's 孫從添 (1692-1767) Bookman's Manual (Cangshu jiyao 藏書紀要).[2] Further translations will follow later this year in a special issue of China Heritage Quarterly devoted to the history of the private libraries of China. Finally, I would like to thank both the editor of China Heritage Quarterly, Geremie Barmé, for an invitation to include the following pages from Wei Li's book in this issue of his journal, and for his invaluable help in preparing them for publication, and Wei Li himself for his kind permission to do so.—Duncan Campbell. Introduction:As does the fish know best the temperature of the water in which it swims, so too does a book collector of long standing (such as myself) appreciate fully the ever alternating joys and sorrows of his quest. Whenever the day has stilled and the night closes in around me, I take up one or other of the volumes from my collection. The collector's seals that I find gathered on the title page, one below or beside the other, tell a silent tale of the fate of the book at hand as it has been passed on from one collector to another, tell of the hardships endured in its collection, tell of the mixed joy and sorrow incumbent on the fact that just as collections are assembled, so too will they inevitably be dispersed. The transmission of a people's cultural traditions, the summing up of the lessons to be gained from historical experience, the recording of the anecdotes of the past—all these are reliant entirely upon the book. And yet, although it is said that 'paper lasts a thousand years' (zhi shou qiannian紙壽千年), of our cultural heritage that which is most prone to destruction, that which proves most difficult to preserve for future ages, is the book. Often we read reports of remarkable discoveries (be they of gold or porcelain or stone) newly unearthed; only seldom, however, do we hear of the discovery in these archaeological digs of a book printed on paper. Little wonder then that in their wisdom the ancients spoke of the Four Plagues of the Book: flood, fire, warfare and insect.  Fig. 3 The Collector's Seal of the famous early Qing dynasty scholar Zhu Yizun (1629-1709) whose library, Pavilion for Airing My Books, was discussed in China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 13 (March 2008). From Lin Shenqing, ed., Ming Qing zhuming cangshujia cangshuyin, p.77. I then find myself thinking, by association, of all the rare books housed in the major libraries throughout our land. We all admire the splendid holdings of these libraries; few give even a passing thought to the generations of book collector whose painstaking efforts have made these books available to us, to those bibliophiles of old who have passed on to us the torch of learning. Whenever such thoughts came to me I would become absorbed by the idea of a grand scheme: to seek out and to visit each and every one of the private library buildings. These 'Cangshulou' 藏書樓 of old were once found scattered throughout China. In my quest I would attempt to visit them and to describe what I found, even if all that remained was no more than the site itself. Almost five years have now passed since I set out on my quest in 1997. The vicissitudes encountered during dozens of excursions are hard to put into words. Regardless, I have managed to assemble a stack of notes and photographs. Of the eighty or so libraries that I did locate, four have since been destroyed. In the case of five others, however, the relevant cultural office or tourism bureau has written to me to thank me for my 'discovery' of a new site for commemoration or one that may serve as the focus for a publicity campaign. In an age of rampant materialism, an age in which even the educated speak only of profit, I do not know whether this is simply a sign of the times. What I do know is that I am quite happy to cleave true to my antiquated pursuits and to shoulder the burden of the tasks left to us by the venerable collectors of old. After all, the role of the pacesetters in our society can only be appreciated relative to those who are somewhat more backward. I for one admire most of all backward individuals who work anonymously so that cultural traditions may be passed on from one generation to the next. All that I can hope for is that, as a result of my work, people will occasionally think of the individual bibliophiles that I discuss below. This then is how I excuse this little book of mine.—From Wei Li 韋力, Shulou xunzong 書樓尋踪, Shijiazhuang: Hebei Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 2004.

Hall of the Variegated Robe (Caiyitang 采衣堂)[3]Immediately upon arriving in Changshu, we set off in search of the Hall of the Variegated Robe, the library that had once belonged to the Weng family 翁氏. To our considerable surprise, we soon arrived at out destination, along Book City Street. A newly erected stone ceremonial arch bearing (in gold) the words 'Ward of the First Place Getters' (Zhuangyuan fang 狀元坊) marked the place, and twenty meters down a little lane through that arch we caught sight of a large mansion, the front gate of which, by stark contrast, was only a very little bit larger than that of an ordinary house. If but for a plaque that read 'Former Residence of the Weng Clan' along with a notice set into the wall from the Changshu Heritage Preservation Bureau that read: 'Former Residence of Weng Xincun',[4] we would never have guessed that this was the place we had come to visit. Previously, I had never associated the Weng family with book collecting. The member of the clan that I had been most familiar with was Weng Tonghe 翁同龢 (1830-1904), tutor to two emperors.[5] Any discussion of the 1898 Reform Movement, after all, invariably makes mention of his support for the reforms. It was only the return of Weng family's book collection to China and its appearance on the market that alerted me to the extent to which, over six generations, the Weng's had been major bibliophiles.[6] Sometime towards the middle of last year, Ta Xiaotang 拓小堂, Director of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Section of China Guardian Auction Company, rang me to say that he had obtained some remarkable rare books that had long disappeared from sight. He wondered if I wished to have an advance viewing of them. The prospect excited me greatly and I visited the company offices as soon as possible. There on the long table of the company's well-appointed Reception Room were arranged, by lot, a selection of old books. As I slowly browsed my way through them, Ta Xiaotang spoke in considerable detail about them and of the roundabout and long-drawn out process whereby he had obtained them. Bit by bit I became aware of the importance of the collection. Fourteen titles in the present lot were imprints of the Song or Yuan dynasties, including, for instance, the following important works: Collected Rhymes (Ji yun 集韻), in 10 fascicles and printed in Mingzhou sometime during the reign of the Southern Song emperor Gaozong (r.1127-62), this being the earliest extant printed edition of this work. Shao Yong's 邵雍 Inner Chapters on the Observation of Things (Shaozi guanwu pian 邵子觀物篇), printed in Jianning in Fujian Province during the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), the finest example of such an imprint, and the only extant copy. Surrounded by such treasures, it was as if I had woken up in paradise. So this is what it meant to be a major book collector! At the same time, however, a pressing question came to mind. Amongst the Weng family collection there had been many famous books, some of which carried important prefaces, but these volumes had disappeared from sight for many years and nobody seems to have been aware that they had found their way into this particular collection. Already by the early years of the Republic [1910s], nothing was known about the Weng family's collection, to the extent that when the Japanese bibliographer Shimada Hikosada 島田翰曾 came to China during this period to investigate the whereabouts of China's famous private book libraries, he could find nothing out about it, concluding in his report on the trip, entitled 'On the Fate of the Books from the Tower of the of the Two Hundred Song Imprints' (Paisonglou cangshu yuanliu kao皕宋樓藏書源流考), that of this collection: '…not a single letter or slip of paper remains'. Now that the entire collection had made its extraordinary reappearance, one was faced with the need to explain why it had been that the family had kept the existence of their remarkable collection such a closely guarded secret? The answer to this particular mystery, it seemed, could only be found within the modestly proportioned gate that we found ourselves standing outside.  Fig. 4 The Collector's Seal of the Pavilion of the Source of the Oceans owned by the Yang family of Liaocheng in Shandong Province. From Lin Shenqing, ed., Ming Qing zhuming cangshujia cangshuyin, p.174. Weng Tonghe, fourth son of Weng Xincun 翁心存, took first place in the metropolitan examinations of the sixth year of the reign of the Xianfeng 咸豐 emperor (1856), after which he held successive posts such as compiler in the Hanlin Academy, assistant director of the provincial examinations of Shaanxi, libationer of the Imperial Academy, sub-chancellor of the Grand Secretariat, vice-president of the Board of Revenue, president of the Censorate, president of the Board of Punishments, president of the Board of Works, and Grand Councilor, besides which he served as tutor to both the Tongzhi 同治 and Guangxu 光緒 emperors. He absented himself from his official duties and returned home during the 1898 Reform Movement, following the defeat of which he was dismissed from all his various posts, never again to hold office. His father had been a book collector of some considerable note but almost his entire collection had been destroyed in 1860 during the warfare associated with the Taiping Rebellion. Weng Tonghe too devoted his energies to the acquisition of books and, once he had achieved official prominence, he slowly began to acquire many treasures. Sitting in the capital, he took great delight in being surrounded by his collection. At the time, the Song and Yuan imprints that had formed part of the Hall of Taking Delight in the Good (Leshantang 樂善堂) collection in Prince Yi's Palace were being sold off by the bundle to both the Wengs and Yang Shaohe 楊紹和 (1831-76), master of the Pavilion of the Source of the Oceans (Haiyuange 海源閣). There were so many rare books in Weng Tonghe's collection that the contemporary bibliophile Fu Zengxiang 傅增湘 (1872-1950) wrote in his Bibliographical Notes on the Books in the Garden of Collections (Cangyuan qunshu tiji 藏園群書題記) that: Many of the books in Weng's collection were both rare and held in secret, and included, amongst those that I was able to view, Song dynasty imprints of A Collection of Su Shi's Poetry: Annotated (Shi Gu zhu Su shi 施顧注蘇詩), A Record of Admonitions (Jianjie lu 鑒戒錄), History of the Latter Han Dynasty (Hou Han shu 後漢書) (published during the Shaoxing reign period, 1131-62), an edition of the Selections of Refined Literature (Wenxuan 文選) published in Ganzhou, and a copy of the Garden of Tales (Shuoyuan 說苑) produced during the Xianchun reign period (1265-74). I hear that in late life he obtained a Song imprint of Collected Rhymes, this inspiring him to take the additional name 'Studio of Rhymes'. Of the books listed above, only this one did I not manage to gain sight of, so I note its presence here for the sake of whoever in the future will seek to update Ye Changchi's 葉昌識 (1847-1917) Biographical Poems on Book Collectors (Cangshu jishi shi 藏書紀事詩). In 1871, Weng Tonghe had written a colophon to his copy of A Collection of Su Shi's Poetry: Annotated that noted that he had 'sighed at its uniqueness' and that, upon obtaining it from the Prince Yi's Palace collection for twenty taels, he noted that 'the calligraphic strokes are clear and powerful, shimmering still like a bright pearl, and I fear that no other copy of the work exists'. Pan Zuyin 潘祖蔭 (1830-90)[7] also added a colophon to the work declaring it to be a 'veritable phoenix amidst the stars' and noted that: 'Having obtained this work, Weng Tonghe only very rarely allowed anyone else to look at it, entrusting me alone to write a colophon for it. The joy occasioned by this task knew no bounds'. We went up to the gate and knocked. After a while, an old man came out to tell us that the library was presently under restoration and was no longer open to the public. If we really wanted to take a look around we would need to come back in a few months. However much the two of us argued our case, pleading with him about how far we had come, he seemed unmoved by our entreaties. This impasse continued some time before a young woman poked her head out the gate to see what was going on. Perhaps by virtue of his greater eloquence, or maybe owing to the long hair that lent him a somewhat artistic air, even before my companion had time to address her, we found ourselves finally within the gates of the mansion. With the young woman as our guide, we were taken through the entire complex, learning of the uses to which all the various rooms had once been put. It was only once we were inside that we realized exactly how very large the residence actually was, comprising five separate courtyards. Although some of the rooms were indeed presently under repair, the complex as a whole, the architectural style and the details of its decorated beams and painted rafters particularly, bespoke the prominence and wealth of the family. In one courtyard, we saw a plaque over the lintel of a door that read: 'Library'. Ms Zhang explained that this was where the clan's book collection had once been housed. Upon entering, we found that no trace of the books remained and the room contained little more than a few pieces of old furniture. Before we had given vent to a sigh or two about the fate of the collection, however, out of the corners of our eyes we caught sight of what had once been the main plaque of the library, propped up in a corner. It bore the words 'Hall of the Variegated Robe'. Ms Zhang explained that it was considered too old and had been taken down in preparation for the installation of a new one. After pleading with her for some time, she allowed us to lug it out into the courtyard and take some photographs of it. Were it not for the fact that we still have a number of stops to make on our excursion, I really would have tried to 'inveigle' this plaque into my possession! As we slowly made our way around the mansion, a possible explanation to the mystery began to dawn upon me. Just as the library complex was designed to give no real indication of its size and splendour from the outside, so too had the quality of the book collection been kept a secret from outsiders. Weng Tonghe's position as tutor to the emperor, it seemed, had necessitated both these circumstances. As the old saying has it, 'To be company for the king is to live amongst the tigers' (ban jun ru ban hu 伴君如伴虎)! I suspect that my conjecture may not be too far from the truth. Bookworm Studio (Maiwangguan 脈望館)Last night I rang Cao Peigen 曹培根, the noted Changshu bibliophile,[8] only to discover that although he had originally intended to accompany us on our trip to the Bookworm Studio, he had been called away to Shanghai on urgent business. He did however give us detailed directions to the library— down the little lane opposite the former residence of the Weng clan. And so, today, once we had concluded our visit to the Hall of the Variegated Robe, we crossed the road and went off in search of what remained of this other library. After wending our way down the lane, however, neither my companion nor I could find the place. There was nothing for it but to ring Cao's house. His wife answered the phone and said that her husband had left instructions that if we had any difficulty finding Bookworm Studio, she was to come to our assistance. Despite our best attempts to dissuade her, she soon turned up in a taxi—such are the relationships forged through the love of books!  Fig.5 A painting by Wang Xian, dated 1642, of the Pavilion for Drawing Water from the Well of the Ancients owned by Mao Jin (1599-1659), one of the most famous book collectors of Changshu and an eminent publisher of fine editions. From Wenming de shouwang: guji baohu de lishi yu tansuo, p.63. With Mrs Cao's help, we soon discovered that we had taken a wrong turn and that Bookworm Studio was to be found in the lane running parallel to the one we had found ourselves in. Soon enough we arrived at the gate and caught sight of the notice of the Jiangsu Provincial Heritage Bureau. The entire complex now housed a confusion of families, and if it weren't for Mrs Cao's efforts, the old man at the entrance would not even have let us in. Once inside, we discovered that Bookworm Studio had formerly occupied the western corner of the courtyard and that the entire building had been very well maintained. With wooden floors and well preserved roof beams, the building was about 100 square meters in size— a great deal smaller than the Pavilion of Heaven's Oneness (Tianyige 天一閣) in Ningbo but, nonetheless, the second oldest of all the libraries that I had visited. During the long years of the reign of the Wanli emperor of the Ming dynasty, Zhao Yongxian 趙用賢 (1535-96)[9] served as Left Vice Minister in the Ministry of Personnel. Both he and his son, Zhao Qimei 趙琦美 (1563-1624), were avid book collectors and the catalogue of their library, entitled Catalogue of Zhao Yongxian's Books (Zhao Dingyu shumu 趙定宇書目) lists over 3,300 separate titles. His son's catalogue of his own acquisitions was called Catalogue of Bookworm Studio (Maiwangguan shumu 脈望館書目) and of particular note in this collection were the texts of Yuan and Ming dynasty plays that it contained. When he rediscovered them in 1938, the noted bibliophile Zheng Zhenduo 鄭振鐸 (1898-1958) proclaimed the find second in importance only to the discovery of the Dunhuang manuscripts.[10] The 242 titles that remain are now held in the National Library in Beijing. Once he had been introduced to us by Mrs Cao, the old man who lived there now sat down with us and talked about the library's present circumstances. He was about sixty years old and had come to live here in 1947. Originally, he told us, the Zhao mansion complex had comprised five linked courtyards, two of which had been burnt to the ground during the war with Japan. Of the three remaining courtyards, only the innermost dated from the Ming dynasty, the others having been restored during the Qing period. Surprised at his detailed knowledge of the architectural differences between the dynasties, I asked him to elaborate and he explained that whereas the roofs of the Ming dynasty tended to be concave, those of the Qing were flat. He went on to say that the fine cedar pillars and decorated bricks had all been smashed by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. Thanking the old man, we wandered out into the courtyard were we came across some old ladies. 'So many people have turned up here in the past few years to look at this building', one said to another, 'I really don't know what they are looking at!' Hearing this, I was delighted—I was not alone in my quest, it seemed. The final words of Lu Xun's (1881-1936) essay 'Written for the Sake of Forgetting' (Wei le wangquede jinian 為了忘却的紀念) came to mind: 'Even if it wasn't to be my part to do so, there would finally come a day when they would be remembered and again be spoken about' (Jishi bushi wo, jianglai zong hui youjiqi tamen, zai shuo tamen de shihou de 即使不是我,將來總會有記起他們,再說他們的時候的).[11] Studio of Nourishment in Tranquillity (Jingbuzhai 靜補齋)The Studio of Nourishment in Tranquillity in Changshu was once the library of Li Zhishou 李芝綬 (d.1893). Li Zhishou passed the provincial examinations of the nineteenth year of the reign of the Daoguang 道光 emperor (1839), and his collected writings, Collection of the Studio of Nourishment in Tranquility (Jingbuzhai ji 靜補齋集), is still available. He was a close friend of the Qu 瞿 family, owners of the Tower of the Iron Lute and Bronze Sword (Tie qin tong jian lou 鐵琴銅劍樓), and so, as his skills of bibliographic discrimination improved, so too did his own book collection begin to grow. In his entry on Li Zhishou in his Biographical Poems on Book Collectors (Cangshu jishi shi 藏書紀事詩) (1910), Ye Changshi 葉昌識 (1847-1917) wrote of this man: Whilst I was visiting Qu Bingqing 瞿秉清, Qu Yong's son, sometime around 1872, I caught sight of Li Zhishou sitting in his study… I have heard that Li is also extremely well versed in matters bibliographical, and, besides, is very knowledgeable about local history and traditions. He too has a large collection of rare books. This illustrates the intimacy of the relationship between these two book collectors. Only one courtyard of the library remains today; smallish, it takes up little more than half a mu. My assessment of the architectural features of what remains of the complex suggest that it does, nonetheless, in fact date from the time of the library. The building is presently occupied by a family, none of whom seem to know anything about Li Zhishou. Translator's Notes:[1] By means of a reversed pun on a comment made to Wei Li by a friend when he caught sight of his book collection ('What a pile of waste paper (lanzhi) you have here' 你這裡有這樣多的爛紙啊), the name of the library seems to derive from a line in the fourth of the 'Nine Songs' ('The Lady of the Xiang' [Xiang furen 湘夫人]) of the Songs of the South (Chuci 楚辭) that goes, in David Hawkes's translation: 'The Yuan has its angelicas (zhi), the Li has its orchids (lan)' (沅有芷兮澧有蘭), for which, see David Hawkes, trans., The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985), p.108.

[2] For a complete translation of this work, see Achilles Fang, trans., 'Bookman's Manual', Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, vol.14, no.1/2 (1951), pp.215-260. [3] The name of the library derives from the story of Lao Laizi, as found in the Yuan dynasty work Twenty-four Examples of Filial Piety (Ershisi xiao 二十四孝), who, we are told, at the age of over seventy would still dress himself in the colourful clothes of his youth in order to amuse his parents. [4] For a biography of Weng Xincun 翁心存 (1790-1862), see A. W. Hummel, Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644-1912) (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1944) (hereafter, ECCP), vol.2, pp.858-59. [5] For a biography of Weng Tonghe, see ECCP, vol.2, pp.860-61. [6] In order to protect the Weng family's book and art collection from the ravages of war, the present owner, the author, historian and artist Wan-go H.C. Weng 翁萬戈 (b. 1918), Weng Tonghe's great-great-grandson, had it removed to the United States of America in 1948. In 1985, the book collection went on public display for the first time, arousing much international interest. In 2000, China Guardian Auction Company helped broker a deal whereby, at the cost of US$4.5 million, the book collection was acquired by the Shanghai Municipal People's Government and entrusted to the care of the Shanghai Library. In conjunction with a recent exhibition (11 April-12 July 2009) of the calligraphy and paintings from the collection, at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, a catalogue has been published by the Huntington Library Press: June Li, ed., Treasures through Six Generations: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy from the Weng Collection. [7] On whom, see (in English), ECCP, vol.2, pp.608-09. [8] A recent collection of Cao Peigen's essays on the book collecting traditions specific to Changshu has been published in the same series as Lingering Traces, entitled Accounts of Book Town [Shuxiang manlu 書鄉漫錄] (Shijiazhuang: Hebei jiaoyu chubanshe, 2004). [9] For a short English-language biography of this man and his son, see L. Carrington Goodrich and Chaoying Fang, eds, Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644 (New York & London: Columbia University Press, 1976), vol.1, pp.138-40. [10] Zheng Zhenduo recalls both his excitement of 'This unforgettable day, this moment that I will forever remember' and the strenuous efforts he had to make to secure the books in his 'Colophon to the Manuscript Copies of Plays Ancient and Modern from Bookworm Studio' (Ba Maiwangguan chaojiaoben Gujin zaju 跋脈望館鈔校本古今雜劇), in Zhenduo's Booknotes (Xidi shuhua 西諦書話) (Beijing: Sanlian shudian, 1983), vol.2, pp. 419-79. [11] This essay, dated 7-8 February 1933, was written to commemorate the death, two years earlier at the hands of the government, of five young writers. For a translation of the essay, see Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, trans., Lu Xun: Selected Stories (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1980), vol.3, pp.234-46. |