|

||||||||

|

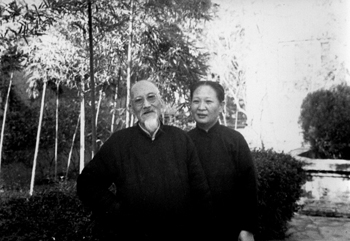

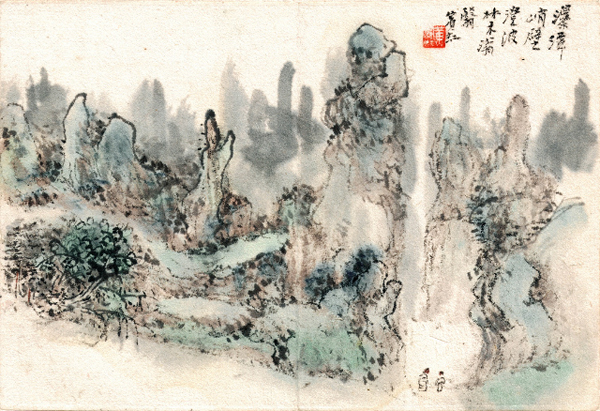

NEW SCHOLARSHIPFriendship in Art: Fou Lei and Huang Binhong (working title)Claire RobertsIntroducing a forthcoming book from Hong Kong University Press.  Fig.1 Huang Binhong and his wife Song Ruoying at home in Qixialing, Hangzhou, photographed by Fou Lei in 1954. Reproduced courtesy of the Fou Family Trust This book charts a friendship between two creative individuals who played important and yet very different roles in the evolution of Chinese culture in the twentieth century. In 1943, Fou Lei 傅雷 (1908-1966), a young Shanghainese intellectual who had spent time in Paris, wrote to the eighty-year-old artist Huang Binhong, a man more than forty years his senior. Huang Binhong 黃賓虹 (1865-1955), also from the south, was then living in Japanese-occupied Beiping (the name for Beijing from 1928 to 1949), isolated in the unfamiliar, politically oppressive city. While the paths of the two men had crossed years earlier in Shanghai, Fou Lei's letter marks the beginning of an intense artistic conversation that continued until Huang Binhong's death in 1955. In his first known letter to Huang Binhong, Fou Lei writes: We met eight years ago on a convivial occasion at the home of [Liu] Haisu and since then I have often regretted that I have not benefited from your wisdom. I remember seeing a series of ten or so horizontal format works that you painted of Emei Mountain and exhibited at the [Shanghai] Art College. They left a strong impression that I have never forgotten. This year I have spent a lot of time at the home of my relative Mo Fei [Gu Fei] where I have learnt about your profound views on painting. I am filled with heartfelt admiration for it is not only in China that ancient methods are relied upon [as sources] for renewal. The case of modern Western art may be looked at for comparison. Regrettably few people in the world comprehend this and even fewer put it into practice.  Fig. 2 Fou Lei and his wife Zhu Meifu, Hangzhou, 1936. Reproduced courtesy of the Fou Family Trust It is rare for an artist to find someone who truly understands his or her work—particularly a person from another generation with very different life experiences. Fou Lei's friendship with Huang Binhong gave both men an opportunity to develop their shared interest in Chinese painting and philosophy, art theory and connoisseurship through conversations that ranged backwards and forwards in time. Over the course of twelve years, the two men exchanged numerous letters and Fou Lei amassed a large collection of Huang's paintings, many of which came with the letters in the mail. Huang found in Fou an unusually astute mind and admiring eye. Fou wrote to Huang with observations and critiques that served to hone his own views on modern art and art history. His perceptive and candid comments enabled the elderly artist to consider Chinese art history and his own work from a perspective informed by an appreciation of modern Western art. Fou Lei is best known as a translator. Little is known about his role as art critic, essayist and collector of contemporary Chinese art. The fragmentary texts, letters and paintings that remain from his artistic dialogue with Huang Binhong spanning the period 1931-1962, provide a way into mental worlds of both men. These documents related to the evolving friendship between Fou Lei and Huang Binhong lie at the heart of this book. Through a careful reading of Fou Lei's writings we can appreciate his interest in probing philosophical questions, his desire to solve problems and his frequent and fearless candour in drawing attention to deficiencies. We also come to share his understanding of Huang Binhong's art. In 1961, six years after Huang Binhong's death, Fou Lei wrote to his friend Liu Kang, whom he had first met in Paris, and summed up the significance of Huang Binhong's art: Among famous recent artists, with the exception of [Qi] Baishi and [Huang] Binhong, all have sought fame through deception, but I suspect Baishi did not read enough books and did not have enough contact with traditional art (he only worshipped Jin Dongxin [Nong], and stopped there), whereas Binhong was an artist of wide learning and did not depend on any one particular artist or school. He was familiar with the art of the Tang and Song and drew on the strengths of historic artists and created his own style. What is most precious about him is that he purely sought to transmit the spirit of historical artists, not their styles. He had the ability to use a completely new brush technique and give you the spirit of Jing Hao, Guan Tong, or Fan Kuan, or the artistic conception of Zijiu [Huang Gongwang], Yunlin [Ni Zan], Shanqiao [Wang Meng]. His skill in realism (I am referring to the sketches he made while travelling) exceeds any of the brush and ink artists of the last few hundred years, and even a few of the most brilliant and famous Chinese practitioners of Western art would have difficulty in being compared to him. His ability to summarise and synthesise form was very strong. He painted in a great number of styles throughout his life and triumphed in old age. Works dating from around the time he was sixty do not display a fully mature style. It was only at the age of seventy, eighty and ninety that he reached the summit of his achievement. In my opinion, in terms of his ability to synthesise the work of earlier artists, after Shitao there is only Binweng [Huang Binhong] (I only dare say this because I have been collecting his work for more than twenty years and have more than fifty of his finest works. Of those paintings that are in circulation only one in ten is a masterpiece).  Fig. 3 Huang Binhong, 'Yangshuo' album leaf, ink and colours on paper, 1948. Reproduced courtesy of the Fou Family Trust The names of Fou Lei and Huang Binhong mean 'thunder' (lei 雷) and 'rainbow' (hong 虹) respectively. Their words and images, like thunder claps and rainbows, are products of a stormy time that presented extraordinary challenges for advocates of modernity and tradition alike. Today in China a diversity of practice is increasingly tolerated in an atmosphere of political nationalism and cultural unity that also embraces the Chinese diaspora. As contemporary Chinese artists, writers, intellectuals and officials continue to navigate complex courses between their own and other cultures, the life and work of these two towering cultural figures from an earlier time who found friendship in art offers a rich legacy. |