|

|||||||||||

|

NEW SCHOLARSHIPLetters by Yuan Hongdao 袁宏道 Selected from his Deliverance Collection 解脫集Translated by Duncan M. CampbellWith Helen Gruber, Han Lu, Jiang Qian, Andrew Ritchie and Yang BinDepartment of Chinese Studies School of Culture, History and Language College of Asia & the Pacific, ANU

—Jiang Yingke 江盈科, 'Second Preface', Deliverance Collection The Buzz of ImplicationThe various collections of the writings of the notable late-Ming man of letters Yuan Hongdao 袁宏道[1] that were published in his lifetime contain almost 250 of his personal letters 尺牘[2]: Brocade Sails Collection (錦帆集 , 1596; 102 letters); Deliverance Collection (解脫集, 1597; thirty letters); Vase Studio Collection (瓶花齋集, 1606; sixty-two letters); and Jade Green Bamboo Hall Collection (瀟碧堂集, 1606; fifty letters).[3] In addition, another thirty or so of his uncollected letters were uncovered and published soon after his death. The literary critic Lionel Trilling once spoke of 'the buzz of implication which always surrounds us in the present'. And if some of the charm of the past, he continues, derives from the quiet that falls about us once this 'great distracting buzz of implication has stopped', then 'part of the melancholy of the past comes from our knowledge that the huge, unrecorded hum of implication was once there and left no trace'. 'From letters and diaries', however, 'from the remote, unconscious corners of the great works themselves, we try to guess what the sound of the multifarious implication was and what it means.'[4] Yuan Hongdao's personal letters allow us to hear again something of the 'hum of implication' that was so much a feature of his life: his relationships with friends and family; his network of official colleagues and fellow writers; his meditations on how his present circumstances often seemed out of keeping with his authentic self. They also afford us a privileged position from which we can observe the development both of his particular literary style and of the theory that underpinned it. If, as Stephen Owen has argued, Yuan Hongdao is the first Chinese literary thinker 'to suggest the essential historicist position that the past is "superseded" ',[5] then his awareness of his own contemporaneity derived surely from his close engagement with the details of the rapid changes in his own age and the 'authentic emotions' that only flow from 'real situations'.[6] Yuan Hongdao gives voice to this sensibility in 'The Imperial Training Ground', written when he was touring Hangzhou in 1597:

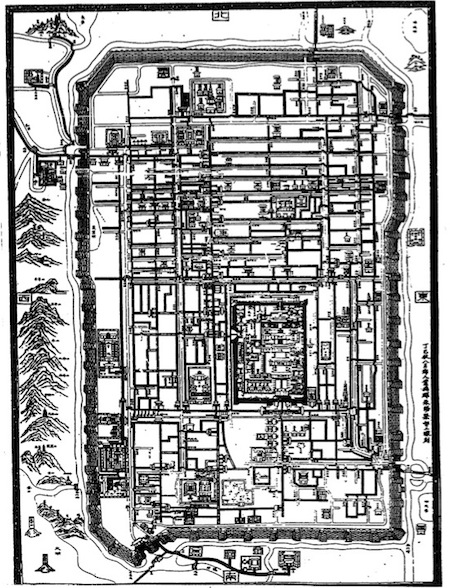

Reading Yuan Hongdao's Letters Fig.1 Map of Suzhou The letters translated below formed the material covered in an advanced course in classical Chinese held in the ANU China Institute seminar room during the second semester of the 2011 academic year. The all date from the Twenty-fifth Year of the long reign of the Wanli emperor, a year that equates roughly with 1597 in the Gregorian calendar. They were first published in Yuan's Deliverance Collection of the same year.[9] Having spent the first twenty years of his life preparing himself for the official career expected of a man of his social status, Yuan Hongdao embarked upon it with a decided ambivalence. Posted to the bustling and prosperous city of Suzhou (then administratively within the Southern Metropolitan Region) in the Twenty-third Year of the reign of the Wanli Emperor (1595) as Magistrate of Wu County, his letters of that year and the next to his friends and relatives provide an eloquent insight into the increasing and almost pathological distaste he developed for the various tasks now required of him.[10] In 1598, shortly after he had returned to Peking to take up the lowly rank of Instructor, in a letter to a friend he offered this comparison between his circumstances when serving as Magistrate and those of more recent times:

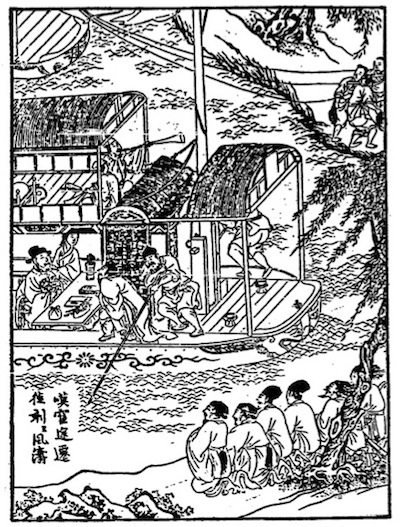

What he seems to have objected to most, as a man with considerable belief in his own talents, was the demeaning nature of his tasks.[12] As the superior, world-weary tone of his letters from Wu County make clear, his interests lay elsewhere. He increasingly resented the extent to which his official duties prevented the indulgence in his 'obsession with the rivers and mountains'. His brother tells us that, during his tenure in Suzhou, Yuan 'wrote nothing of his own and the dust began to settle thick upon his papers'.[13] This contrasts with the extraordinary productivity of the period that immediately follows. Hongdao, it seems—a man who increasingly defined himself in terms of the works he produced—could only embark upon the developing his literary persona when travelling and free from the impositions both of office and of family. Service in Suzhou had not entirely precluded travel of course, but his comments about an official tour he made while there are revealing:

Not a word about the plight of the common people whose livelihood had been destroyed by the floodwaters and whose wellbeing Yuan Hongdao was responsible for! Begging to Retire 乞歸In the spring of the Twenty-fifth Year of the Wanli reign (1597), finally, after repeated requests, Yuan Hongdao was granted leave to quit his post in Suzhou. The last of the seven petitions, first for leave and then for transfer, that he wrote to his superiors is revealing. 'I am an idle and neglectful man', he claims:

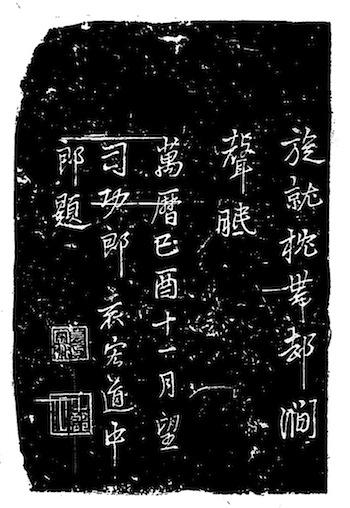

Once released from the confines of official office, Yuan's return home, if ever actually intended, became impossible. His father wouldn't countenance it: 'How on earth can someone hang up their carriage at the age of twenty-eight!', he fumed.[16] Instead, Yuan Hongdao borrowed some money for the upkeep of his wife and child and put them in the care of a friend in Zhenzhou until his younger brother Zhongdao turned up to look after them.[17] Thereupon the older brother Yuan embarked on an extended tour of some of the most scenic and historically resonant sites of the world of the late-Ming man of letters.[18] In the company of his friend Tao Wangling 陶望齡, then back in Shanyin on leave from his post in the Hanlin Academy, Yuan Hongdao visited West Lake, the sacred site par excellence and the focus of the December 2011 issue of China Heritage Quarterly, for the first time, to sit drinking at Lake Heart Pavilion as the autumnal rains washed the lake red with peach blossoms. He paid calls upon the celebrated monk Zhuhong (祩宏, 1535-1615) at his Cloud Perch Monastery. In Wuxi, he sat for hours in the evenings, wearied by a day with his books or out on some excursion or another, listening to Old Storyteller Zhu recite episodes from the novel Water Margin. In Guiji he sought out the 'true' site of the famed Orchid Pavilion where, more than a thousand years earlier, in 353, Wang Xizhi (307-65), the greatest of all calligraphers, had written his immortal 'Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection'. He went boating on Mirror Lake, tasted the famed water mellow of Lake Xiang, and climbed Yellow Mountain. Sitting one evening in his friend Tao Wangling's study in Shanyin he came across a tattered edition of the poetry of the eccentric poet and playwright Xu Wei (徐渭, 1521-1593); he later immortalised this moment in a biography of Xu that served as something of a literary manifesto of the Gongan 公安 school of literature with which Yuan Hongdao is associated.[19] The letters translated below allow us, therefore, some insight into Yuan Hongdao's state of mind during these formative few months of freedom both from official duties and from family obligations, months during which we can observe the realisation of his ideas about the nature and role of writing. The Letters 尺牘To Zhang Youyu 張幼于[20]To have doffed my black magistrate's cap and to have become a vagabond of West Lake is akin to suddenly having quit Hell and finding myself transported to Paradise itself. Such are now my indescribable circumstances. From today onwards I intend to stand guard here amidst the hills and the valleys and to manage my own destiny. No longer will I need to turn my back upon this human world of ours. Oh, what joy! Long ago, the Western Jin scholar Huangfu Mi did not include a record of the lives of the two Gongs of Chu in his 'Biographies of the Recluses'. This was because both men had served in office, if only for the shortest possible time. Having myself, then, served as county magistrate for something over six hundred days, I fear that my biography will no longer be eligible to stand alongside yours within the same category. But then again, the biographies of both the poet Tao Qian, who also served in office, and Qian Lou, that quintessential recluse of whom Tao wrote about, are both to be found in the category of the recluse. With this as a precedent, then, I need have no regrets. Wanli 25 [1597], Hangzhou 擲却進賢冠作西湖蕩子如初出阿鼻乍升兜率情景不可名狀自今以往守定丘壑割斷區緣再不小草人世矣快哉。 昔士安作傳不錄兩龔六百日縣令恐遂不得與幼于同傳但彭澤黔婁業已先之舊史俱編入隱逸矣,何恨哉。 To the Flourishing Talent Feng Qisheng 馮秀才其盛To have sundered the Net of the Dusty World and to have ascended to the Hub of the Immortal, to have escaped from the prison house of officialdom and to have been reborn in the house of the Buddha, this surely is the highest form of afflatus afforded man amidst the dust and the sand of this world! After all, that the parrot likes not its gilded cage but loves the mountain ridges is because that cage fetters its body. That both the eagle and the dove die not among the desolate hazel trees and wild grasses but rather in the paddy and grain fields is because it is the latter circumstances that offend against their natures. If all the creatures thus know intuitively what it is that is most agreeable to them, then why is it that man alone shackles himself with cap and robe and seeks to nourish himself on the emoluments of office? This is ridiculous in the extreme. My recent bout of illness was such that I almost died, and I count my blessings that I have survived the ordeal intact, my body now akin to the excrescence of the Hell of Ghosts. If, in such extremis, I did not finally realise that it was time to retreat, could I still be called a man? Frequently during my illness I have been favoured by your kind thoughts. Now, all of a sudden, I have received from you this present gift of a statue of Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. Such has been the extent of your continuing concern for me. I have long had this in mind to say to you. My gratitude knows no bounds. Wanli 25 [1597], Hangzhou 割塵網升仙轂出宦牢生佛家此是塵沙苐一佳趣夫鸚鵡不愛金籠而愛隴山者桎其體也鵰鳩之鳥不死于荒榛野草而死于稻梁者違其性也異類猶知自適可以人而桎梏于衣冠豢飬于祿食邪則亦可嗤之甚矣。 一病幾死幸爾瓦全未死之身皆鬼獄之餘此而不知求退何以曰人病中屢辱垂念忽承大士之賜甚隆素懷走欲言之久矣謝不盡。  Fig.2 The Magistrate Arrives at his Post To Tao Shikui 陶石簣The invalid has finally ridden himself of his office and has arrived at the Lake. How fortunate he would be, my good sir, if you, along with your brothers of course, were now to turn up here for a chat. As soon as possible and as previously arranged. On this trip, the invalid is carrying with him twenty bushels of pearls of Buddhist wisdom and these he really should share with you and your brothers. Wanli 25 [1597], Hangzhou 病夫竟解官矣至湖上矣君家兄弟幸如約早過一譚病夫此來攜得有二十斗珠璣當與君家兄弟共之。 To Tang Yunlu 湯隕陸[21]I hear that the Salt Distribution Commissioner has just arrived in town and I recall from my own experience how you will now be found rushing to and fro along the highway with your name tablet held high above your head. My back aches on your behalf! I am more grateful for your gift of wine than words can possibly express—a true token of the fact that your present busyness has not resulted in the neglect of old acquaintances. As I said to a friend just yesterday, it would have been enough, surely, for us to be staying here in Hangzhou and not to have received an 'Even the Prince Cannot Detain Him' herb from the landlord of the place what happy destiny it is that we have now, conversely, received such favour from you?[22] Your accompanying note reads: 'When the wine is drunk, be sure to come for some more'. Marvellously put, and after I had read it, I repeated it a number of times. I then had my serving boy bring me my brush so that I could underline the sentence. I am a man, it seems, who can truly be said to be courageous in the acceptance of favours from others! Wanli 25 [1597], Hangzhou 聞鹽使者方至因憶令君端執手板奔波道旁腰肢為之作痛麯蘖之賜感不可言紛庬中不忘故人乃爾弟昨與友人言吾儕居此但得地主不餉王不留行足矣何緣復當此橫施哉來札云酒畢再來取此一語甚妙弟讀畢捧誦再過復令小奚取筆旁加數圈然則弟可謂勇于服善者矣。 To Sun Xinyi 孫心易[23]I have tarried one month by the West Lake, and another at the Mirror Lake; an uncouth rustic, lazing indolent among the knolls and gullies, pleasuring my soul with peak and pool; a mild, untroubled sort, I dare not rashly address my words to a man of such high office as yourself, for fear of needlessly arousing his longing for retirement and cooling his devotion to office. I know not where the road ahead of me leads; I know only there is a way ahead, but not what it is. The business of roaming these hills is more taxing than that of office, and so it is in haste that I offer up this reply. More, now, is beyond me. Wanli 25 [1597], Guiji 一月住西湖一月住鑑湖野人放浪丘壑怡心山水一種閑淡不敢輕易向官長言恐無端惹起人歸思冷却人宦情當奈何弟前路未知向何處去唯知出路由路而已。 A Letter on Human Nature Addressed to the Immortal 與仙人論性書[24]Having read Wu Guanwo's mondō 問答, I understand that you, my master, have profound insight and abstruse knowledge.[25] Obviously, expecting both the form and spirit (of your knowledge) to be wondrous, humble scholars in this low realm have been busy cheering for you with great enthusiasm, for how could one dare, presumptuously, put forward a dissenting word? Nevertheless, sonorous bells and Dharma drums do not echo without being struck; even mighty oceans do not reject floating bubbles and fine foam. Attempting to exhaust my very limited capacity, I will, daringly, state my skin-shallow views. Heart-mind is the shadow of the ten thousands things; form the base of the illusory heart; spirit the source of all thought. Birth and death constitute Form; the comings and goings of thought, the Heart; fine and constant flows of consciousness, the Spirit. Form comprises birth and death, Heart-mind does not; Heart-mind comprises comings and goings (of thoughts), Spirit does not. Form is like a sieve; but among all gods that attend to the sieve, only one occasionally arrives at it, thus formation and destruction of the sieve cannot entirely rely on the gods. Suppose that the god takes the sieve as the master of the body, he must have meant to make it so robust that it is immune from destruction, but then he would have also been extremely stupid and confused. Although Heart-mind is not a non-being because of nothing, it must be a being because of something. If one regards it as Spirit, as if it is sieve-less, then it would comprise not that by which it is supported (that is, Heart-mind itself). Because there are questions, there are replies; because there are senses, there are thoughts; because there are differences, there are distinctions. This Heart-mind does not have a past, nor does it differ from tiles and rocks; therefore, that which is called 'preposterous words' are an ignorant man speaking of his erroneous and false untruth, just as common words tell lies and nonsense. Changes of the Spirit are unpredictable—this is that which is called nirvāna—illuminating and self-following. Yet, being unpredictable is predictable, self-following is also from the self; since the self already has its source, then what is this thing called 'following'? Ultimately, it is also a phenomenon shown when the alchemy of Heart-mind and Form has reached its extreme. Although Spirit is separated from organs and senses, in fact it does not leave them. This is what the Śūraṅgama-sūtra means by 'having-thought and having-no-thought set the utmost limit of consciousness. Consciousness is rightly the Spirit. Xuansha says: 'If you go to the autumn Tan River upon which the moon sheds its shadow, you would observe that in the quiet night, the bell sound does neither weaken with the rhythms of hitting, nor does it scatter with the ups and downs of waving—this is like the matter of the shores of life and death'.[26] This refers exactly to the Spiritual Consciousness. This Consciousness gives birth to Heaven and Earth, gives birth to humans and objects; it consists of no perception or knowledge, and it is of itself. Since great sages of the ancient time, all have regarded this Consciousness as the beginning of life; therefore, each and every one of them has fallen into the conduct of action. How many heroes have been drowned? Wouldn't one fear? But, if one disregards the sieve, Form, Heart and Spirit, what is after all the beginning of life? I, your disciple, having reached this point, am indeed as confused as everyone else, and cannot avoid relying on pens and books. All this is just for a laugh or two. You, my master, what your knowledge presently lacks is not related to the body; the single true Nature has continued from the past and will continue from the present—it is not short of immortality. Among hair pores and bone joints, no place is not a Buddha—this is called the wonder of the Form; of greed, anger, mercy or endurance, no thought is not a Buddha—this is called the wonder of the Spirit. In Heaven or Hell, and in the state of being emotionless or emotional, there is no Buddha that is not a Buddha—this is called becoming an immortal. I am only afraid that you, my master, simply have not arrived at such a realm. If you can pass through this barrier, the body, heart-mind and spirit of the ego will all be like a reflection in a mirror or foam in water—would you still worry about calculating the length of life for them? All calculations are a result of not seeing the true Nature and mistakenly regarding the Spiritual Consciousness as the Nature. Having already mistakenly recognised Spirit, then one inevitably recognises the outer cover of Spirit; since one recognises Spirit's outer cover, then one sets Form and Spirit, Nature and Life as opposites. As having opposed Nature and Life to each other, therefore one speaks of cultivating the both; as having opposed Form and Spirit to each other, therefore one speaks of the both as wondrous. All wrong calculations start from here. If it is the true Spirit, the true Nature, it is not that which even Heaven and Earth can hold, that which purity and impurity can leave, that from which ten thousand of thoughts can rise, or that which intelligence and knowledge can enter—how could it be something with which a trivial body could handle? This is merely the low opinion of mine. What would be your profound thought? May your ultimate teaching enlighten me. Wanli 25 [1597], Hangzhou 讀吳觀我問答文字,知師卓識玄旨,斷斷乎以形神俱妙為期,下土賤士,踴躍慶幸之不暇,何敢妄置一辭。雖然,洪鐘法鼓,不叩不鳴,浮漚細沬,巨海不擇,試竭蛙腸,敢陳虜論。 夫心者萬物之影也,形者幻心之托也,神者諸想之元也。生死屬形,去來屬心,細微流注屬神。形有生死;心無生死;心有去來,神無去來。形如箕,然諸仙赴箕,偶爾一至,箕之成壞,無與於仙。若使為仙者認箕為我,必欲使之堅固不壞,則亦愚惑甚矣。心雖不以無物無,然必以有物有,辟之神若無箕則無所托。因問有對,因塵有想,因異同有分別。此心無前塵,與瓦石無異,故曰妄言,妄者言其謬妄不實,如俗言說謊扯淡是也。神者變化莫測,寂照自由之謂。然莫測即測,自由亦自,自即有所,由是何物。極而言之,亦是心形鍊極所現之象,雖脫根塵,實不離根塵。 經曰「湛入合湛歸識邊際」是也。識即神也。玄沙云:「縱汝到秋潭月影,靜夜鐘聲,隨叩擊以無虧,逐波濤而不散,猶是生死岸頭事。」正是指此神識。此識生天生地,生人生物,不識不知,自然而然。從上大仙,皆是認此識為本命元辰,所以個個墮落有為趣中,多少豪傑,被其沒溺,可不懼哉!然除却箕,除却形,除却心,除却神,畢竟何物為本命元辰?弟子至此,亦眼橫鼻豎,未免借註脚于燈檠筆架去也。笑笑。 夫師現今有知所不足者,非身也,一靈真性,亘古亘今,所不足者,非長生也。毛孔骨節,無處非佛,是謂形妙;貪嗔慈忍,無念非佛,是謂神妙。天堂地獄,無情有情,無佛非佛,是謂拔宅飛身,但恐師未到此境界耳。若透此關,我身我心我神,皆如鏡中之影,水上之沫,有何間圖度為他計算長久哉?一切計較,皆緣見性未真,誤以神識為性。既誤認神,便未免認神之軀殼,既誤認軀殼,便將形與神對,性與命對。性與命對,故曰性命雙修;形與神對,故曰形神俱妙。種種過計,皆始於此。若夫真神真性,天地之所不能載也,淨穢之所不能遺也,萬念之所不能緣也,智識之所不能入也,豈區區形骸所能對待者哉?鄙意如此,不知玄旨以為如何?唯終教之。 To Chen Zhengfu 陳正甫[27]With travelling companions akin to Lu Ao I have chanced upon this place, carried by the clouds and with my flying staff in hand.[28] Upon inquiry of the mortals here, I discovered that we are now in your territory, my good Sir. Along narrow roads are men bound to encounter one another, as the saying goes. I feel compelled to stop here for three days. To this purpose, I entreat you to find for me a clean room beyond the city walls. It need be only clean and fragrant, or if such cannot be found, then perhaps you could have the bookroom on Dipper Mountain swept clean for our use? We will stay in She county no more then three days, before departing for Equal with the Clouds; I trust you will keep this in strictest confidence. Wanli 25 [1597], Wuxi 近日挈盧遨輩竦身雲清偶爾飛錫至此問此下界人始知為尊兄國土既爾狹路相逄不得不為作三日留城外淨室乞一間須淨而香乃可不則打掃斗山上書室也留歙大約不過三日即往齊雲幸勿令人知。  Fig.3 Yuan Hongdao's calligraphy, dated Wanli 37 (1609) To Zhao Wuxi 趙無錫[29]For four months now have I studied the flowers of West Lake, enquired of the Way at Heaven's Eye, and journeyed to Wu and Yue and back again. The miles my feet have trod amount to many thousands, and the mountains my eyes have beheld number in the hundreds. I have produced almost a book full of poems of my travels that have been posted to various people. The days of roaming hills and valleys are yet near, and my days of officialdom are far away; my mind is becoming wild and foolhardy. I merely tell you the details from beginning to end, by way of trading you a joke. My lowly family has long resided in Wuxi now; by rights we are all under your care. We each of us need present our compliments to you. Wanli 25 [1597], Wuxi 弟看花西湖訪道天目往返吳越間四閱月足之所踏幾千餘里足之所見幾白餘山其他登覽贈寄之作亦幾成帙丘壑日近吏道日遠弟之心近狂矣癡矣聊述其顛末以博尊兄一笑賤眷居錫城久似為部下人今者各寫治生帖子矣。 To Shen Guangcheng 沈廣乘[30]Of all the mountains of West Zhejiang Province, none surpasses Heaven's Eye Mountain. Words cannot describe its wondrous beauty. The rocks of the White Crag too are marvellous eccentric in shape, even if slightly monotonous, particularly in comparison to those of Heaven's Eye. Supposing one was to have first climbed White Crag, I'm not at all sure what my opinion would have been about their respective merits? For mountains too, it seems, it is all a matter of chance encounters. Wanli 25 [1597], probably at Tianmu Shan [Heaven's Eye Mountain] 浙西之山無過天目奇邃不可言白嶽石亦奇但稍板大為天目所形若使先登白嶽不知賞識當何如也山固有遇有不遇哉。 To Xu Chongbai 徐崇白[31]Although I am now at some far distance from you, I know that you, my good sir, keep me in mind. It is just that a lazy traveller such as I is devoid of any thoughts of the world of man, and for such a one as I, all writing has become simply a way of amusing oneself. How could I possibly hope to compete with others in that domain? But as to my study of Human Nature, I believe that I have reached a state of some insight. I would contend that my learning in this respect has no match throughout empire, let along amongst the men of Wu county. Nonetheless, in their ignorance, vulgar fellows are constantly trying to correct me. How ridiculous! Chan practice has both intuitions and external causes, and my learning encompasses both these. Such learning is beyond the ken of mere literary or artistic men. I've been thinking of returning for several days, and once my friend Fang Zigong turns up here, I will be off. I beg you not to try to follow me. Wanli 25 [1597], Hangzhou 辱遠使知公念我遊惰之人都無毫忽人世想一切文字皆戲筆耳豈真與文士角雌較雄邪至於性命之學則真覺此念真切毋論吳人不能起余求之天下無一契旨者俗士不知又復從而指之可笑哉禪自有機有鋒生所說者皆機也鋒也學問中事豈宜令文人墨士觀哉數日圖歸方于公或上岸主徑行矣幸勿跡之 To Wang Baigu 王百穀[32]I've read the preface you sent me; it is excellent. Though I have known quite a few famous men over the years, not one of them has so much as mentioned Chan in their writings. As a county magistrate in the Wu area, I had always been frustrated that people there never truly understood me. I had not suspected that you, too, my good sir, were interested in Chan. Is this the only aspect of you that I did not fully appreciate, I wonder? The mountains and rivers of the Wu and Yue region are marvellous, and I have now explored them all, but not one of them have I written about in the manner that you have. When Yao Shilin 姚士粦 departed, I was caught in a rush and missed the chance to express my gratitude to him. I now hasten to write down a few words in the boat and give this letter to Xiaobai 小白, in the hope that he can present it to you. Wanli 25 [1597], travelling between Hangzhou and Wuxi 讀來敘佳甚往歲會諸名士都無一字及禪以故吳令時每以吳儂不觧語為恨不知百穀之有意乎禪也然則僕之不能盡百穀者尚多奚獨禪也吳越佳山水登覽畧盡恨不能一一舉似百穀叔乂去時匆匆未及報謝舟中勒數宇托小白轉致之。 To Qian Xiangxian 錢象先[33]The poems you wrote on the fan are as vivid as a flower, as subtle as autumn, as luxuriant as the mountains and as enticing as the sheen of the river. Lin Bu and Chen Shidao of the Song could not match them, and certainly responding to them appropriately is quite beyond my own inferior talents. What can I do! The mountains and rivers of Wu and Yue are immensely beautiful, and I have now explored the area fully, having managed also to write a volume of poetry and prose. I wish I could have you read them. I plan soon to travel to Qixia Temple to spend the summer. Any chance that you might be able to come by boat to pay a visit? Wanli 25 [1597], Wuxi 扇頭諸絕鮮妍如花淡冶如秋忽翠如山之色明媚若水之光林和靖陳無已不足道也鄙薄不能属和奈何吳越堆山水登覽畧盡詩文已又成帙恨不令錢郎讀之擬即往棲霞度夏有興能棹一舟相訪乎 To Hua Zhonghan 華中翰[34]It has been three months since our goodbyes and during that time I have travelled more than 2000 li. My family now treats your residence as if it's their own home, and I too have come to regard Wuxi as my own hometown. I recall that [the Tang dynasty poet] Jia Dao once composed a poem that went: For no reason did I cross the waters of the Sanggan River All the while, thinking that Bingzhou had become my real home instead. He was complaining, but for me, this circumstance is a pleasurable one. We are not frogs are we, that we should be prone to homesickness? One's hometown, after all, is the home of accumulated hatreds and malicious gossip, a veritable prison house of suffering and misery, a repository of expectations on the part of father, brother, teacher and friend alike. What flavour does one's hometown afford one that we should hanker after it so? In this respect, even Jia Dao seems to have been a bit silly! To be without the burden of wife and child and servant is an extraordinary delight, and one which without your generosity and sincerity I would never have been able to experience. I thank you. However, Wuxi is proving somewhat too close to Suzhou, and on this occasion I cannot stay here long, and intend moving my family to Guabu. Once my poems are enough to form a collection, I'll be sure to sent them to you Wanli 25 [1597], Wuxi 一別三月往返二千餘里家属居尊宅若家不肖望梁溪若鄉賈島云無端更渡桑乾水卻望并州是故鄉不免有牢騷意若僕則樂之矣人豈蝦蟆也哉而思鄉乎夫鄉者愛憎是非之孔愁慘之獄父兄師友責望之藪也有何趣味而貪戀之浪仙亦愚矣哉妻孥僮僕若將終焉此尤事之極奇者非賢主人真心愛客焉得有此謝謝但此地去蘓太近今回亦不可久便欲移之瓜步矣小時成帙當致上。 Notes:[1] Yuan Hongdao (zi Zhonglang 中郎, Wuxue 無學, Liuxiu 六休; hao Shigong 石公, Shitou jushi 石頭居士; 1568-1610), from Gongan County, Huguang province. For short biographies of Yuan Hongdao in English, see L. Carrington Goodrich and Chaoying Fang, eds., Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644, New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1970, vol.2, pp.1635-1638 (by C.N. Tay); and W.H. Nienhauser, ed., The Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986, pp.955-56 (by Ming-shui Hung). Ren Fangqiu 任訪秋, Yuan Zhonglang yanjiu 袁中郎研究, Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe, 1983, includes a useful chronological biography 年譜 of Yuan. For English language studies, see two articles by Jonathan Chaves, 'The Panoply of Images: A Reconsideration of the Literary Theories of the Kung-an School', in Susan Bush and Christian Murck, eds, Theories of the Arts in China, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983, pp.341-364; and, 'The Expression of the Self in the Kung-an School: Non-romantic Individualism', in Robert E. Hegel and Richard C. Hessney, eds, Expressions of the Self in Chinese Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, 1985, pp.123-150; two articles by Richard John Lynn, 'Tradition and the Individual: Ming and Ch'ing Views of Yüan Poetry', in Ronald C. Miao, ed., Studies in Chinese Poetry and Poetics, San Francisco: Chinese Materials Center, 1978, pp.321-375; and, 'Alternative Routes to Self-Realization in Ming Theories of Poetry', in Bush and Murck, Theories of the Arts in China, pp.317-340; and, the full-length study by Chih-p'ing Chou, Yüan Hung-tao and the Kung-an School, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. For English translations of a selection of the prose and poetry of Yuan Hongdao and his brothers, see Jonathan Chaves, trans., Pilgrim of the Clouds: Poems and Essays by Yüan Hung-tao and His Brothers, New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1978. The translators would like to thank the editor, Professor Geremie Barmé, for the many suggestions that have served to much improve these translations, and to Will Sima for inserting the original texts of Yuan's letters. [2] For a succinct discussion of the origins of this archaism (literally, 'foot-long tablet'), see Endymion Wilkinson, ed., Chinese History: A Manual, revised and enlarged edition, Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2000, pp.444-447. [3] Three of the collections of his writings that Yuan Hongdao published in his lifetime contain no letters: Battered Trunk Collection 敝篋集 (containing Yuan Hongdao's earliest poems, covering the years 1584-1591, but only published in 1597); Guangling Collection 廣陵集(1597); and Cracked Inkstone Collection 破研齋集 (1606). Qian Bocheng 錢伯城 in his 'Yuan Hongdao ji jianjiao fanli' 袁宏道集箋校凡例, in The Complete Works of Yuan Hongdao: Annotated and Collated Yuan 袁宏道集箋校 (hereafter YHDJJJ), 3 vols., Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe, 1981, vol.1, pp.1-6, provides a succinct account of the textual history of Yuan Hongdao's writings. Any student of Yuan Hongdao (or for that matter his two brothers, Yuan Zongdao (1560-1600) and Yuan Zhongdao [1570-1624]) is deeply indebted to the excellence of the editorial work of Qian Bocheng and it is his YHDJJJ on which we have relied upon in our work on these translations. Firstly, through exhaustive reference to the numerous early editions of Yuan Hongdao's writings, Qian provides a list of textual variants. Secondly, rather than arranging his collection in terms of genre, he does so in accordance with the collection titles under which Yuan Hongdao's writings were published in his own lifetime. And thirdly, he ascribes a date to each letter, provides biographical information on both the addressees of the letters and other people mentioned in the text of the letters, and includes also the commentaries on Yuan Hongdao's prose and poetry found in a number of late-Ming editions. There is a bitter irony in the fact that just as Yuan Hongdao's collected works were banned during the Qing dynasty, so too did Qian Bocheng's edition of Yuan Hongdao's works suffer at the hands of the state censor; although Qian completed his editorial work on this collection in 1965, political circumstances meant that he had to wait almost twenty years before being able to publish it (see 'Qianyan' 前言, YHDJJJ, vol.1, p.13). [4] Lionel Trilling, 'Manners, Morals, and the Novel', in The Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society, London: Secker & Warburg, 1951, p.206. [5] Stephen Owen, 'Ruined Estates: Literary History and the Poetry of Eden', Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (1988), 10: 33. [6] As Jonathan Chaves, 'The Panoply of Images: A Reconsideration of the Literary Theory of the Kung-an School', p.359 points out, a similar formulation (zhenjing shiqing 真境實情) as that used by Jiang Yingke to describe Yuan Hongdao's letters (see the epigraph to this introduction) was used by Yuan Zhongdao in a 1618 preface to his own writings. [7] Tao Wangling 陶望齡 (zi Zhouwang 周望; hao Shikui 石簣; 1562-1609), one of Yuan Hongdao's closest friends and a frequent travelling companion. [8] 'Yujiaochang' 御教場, YHDJJJ, vol.1, p.435. [9] Aside from the participants listed above, the class was also audited by David Brophy, Nathan Woolley and Zhu Yayun. The translators are grateful for their contributions to the discussions that accompanied our efforts at translation. We are also grateful to the Director of the ANU China Institute, Professor Richard Rigby, for permission to use his seminar room for this purpose, and to Nathan Woolley for making the arrangements. [10] For translations of these letters, see Duncan Campbell, 'The Epistolary World of a Reluctant 17th century Chinese Magistrate: Yuan Hongdao in Suzhou', New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 4.1 (2002): 159-193. [11] 'Da Mei Kesheng' 答梅客生 [In Reply to Mei Guozhen], YHDJJJ, vol.2, p.748. [12] Speaking of the contrast between his two elder brothers, Yuan Zhongdao tells us that whereas Yuan Zongdao, the most successful brother in terms of his official career, was far more prepared to make compromises, Yuan Hongdao 'argued that just as the phoenix did not nest with ordinary birds, nor the Qilin stable itself with the common horse, so too should the real hero (da zhangfu 大丈夫) come and go as he pleased', see 'An Account of the Conduct of Master Yuan Hongdao, Director of the Bureau of Honours of the Ministry of Personnel' 吏部驗封司郎中中郎先生行狀 , in Yuan, Jade White Studio Collection 珂雪齋集, Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe, 1989, vol.2, p.756. [13] Yuan Zhongdao, 'An Account of the Conduct of Master Yuan Hongdao', Jade White Studio Collection, vol.2, p.756. [14] 'Heng Shan' 橫山 [Mt. Heng], YHDJJJ, vol.1, p.173. In Yuan Hongdao's account of his various visits to Tiger Hill, just beyond the walls of Suzhou, he complains that when he turned up there in his magistrate's robes, 'all the singing girls, hearing that the magistrate had arrived, fled into hiding', see 'Huqiu' 虎丘 [Tiger Hill], YHDJJJ, vol.1, p.158. [15] 'Qi gai gao wu' 乞改稿五 [Fifth Petition Begging for Transfer], YHDJJJ, vol.1, pp.322-323. [16] Yuan Zhongdao, 'An Account of the Conduct of Master Yuan Hongdao', Jade White Studio Collection, vol.2, p.757. [17] Yuan Hongdao had married in 1585, at the age of eighteen. He complains about the burdens of family life in the account of his visit to Solitary Hill near Hangzhou, for which see 'Gushan' 孤山 [Lone Hill], YHDJJJ, vol.1, p.427. Jonathan Chaves in his Pilgrim of the Clouds, provides a translation of this essay, the relevant section of which reads: 'Such people as myself and my friends, precisely because we have wives and children, let ourselves in for all kinds of problems. We cannot get rid of them, and yet we are tired of being with them—its like wearing a coat with tattered cotton padding and walking through a field of brambles and stickers that tug at your clothes with each step'.( p.98.) [18] Nelson Wu, 'Tung Ch'i-ch'ang (1555-1636): Apathy in Government and Fervor in Art', describes this world in the following terms: 'As illuminated by the writings and traced by the travels of late Ming intellectuals, this world emerges as a dumbbell-shaped area superimposed on the map of China. The northern end, having as its center the national capital of Peking, was the political arena for all, where prizes in fame, riches, and posthumous titles were given as frequently as severe punishment was meted out. Punitive measures included everything from the immediate clubbing to death of the individual to the stripping from one's family of all accumulated honors and privileges, a punishment sometime more painful than death to the traditionally trained Confucian gentry, followed by the thorough liquidation of all members of the family. Connected to this political nerve center by a narrow passageway roughly paralleling the Grand Canal was the cultural land of the lower Yangtze valley, with such illustrious towns as Soochow, Ch'angchow, Sungkiang, Kashing, Hangchow, and the southern capital of Nanking. This area nurtured Ming developments in Chinese painting and most of the important movements in the intellectual history of the period', in A.F. Wright and D.C. Twitchett, eds., Confucian Personalities, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962, p.262. [19] On this biography, see Duncan Campbell, 'Madman or Genius: Yuan Hongdao's "Biography of Xu Wei" ', in Dov Bing, S. Lim and M. Lin, eds, Asia 2000: Modern China in Transition, Hamilton: Outrigger Publishers, 1993, pp.196-220. In a letter to his friend Wu Hua (吳化, js 1595) dated 1597 Yuan Hongdao was to say: 'The most pleasing aspect [of my recent trip] was that passing through Zhejiang I … unearthed Xu Wei, a man who must, I feel, rank as the foremost poet of our dynasty'. See 'Wu Dunzhi' 吳敦之 [To Wu Hua], YHDJJJ, vol.1, p.506. For translations of his travel accounts of his time at West Lake, see Stephen McDowall, translated and introduced, Four Months of Idle Roaming: The West Lake Records of Yuan Hongdao (1568-1610), Wellington: The Asian Studies Institute, 2000. [20] Zhang Xianyi (張獻翼, zi Youyu), younger brother of the playwright Zhang Fengyi (張鳳翼, 1527-1613), from Changzhou. Author of an important work on the Book of Changes 易經, Zhang was also known for his eccentricity. Seven or so years after the date of this letter to him, he is said to have fled his home with a prostitute and died in mysterious circumstances. [21] Tang Mu (湯沐, zi Yunlu), from Anlu county in present-day Hubei province (then, Huguang). Having become an Advanced Scholar in the Twentieth Year of Wanli (1592), Tang was appointed Magistrate of Qiantang county, where he served for six years before being promoted as Supervising Secretary in the Six Offices of Scrutiny. In 1595, he and Yuan Hongdao had departed the capital together as they took up their respective posts in Hangzhou and Suzhou. [22] Yuan Hongdao's use of the name of this herb, a mild diuretic, alludes to a story found in the 'Stinginess and Meanness' chapter of A New Account of Tales of the World 世說新語 which reads, in Richard Mather's rendition: 'While Wei Zhan was stationed in Xunyang (as governor of Jiang province, ca.308-ca.312), an old friend came to him for shelter (as a refugee from the north), but he provided no entertainment for him whatever, except only to give him one catty of the herb wang-bu-liu-xing. After the man had gotten his present, he immediately ordered his carriage.' See Richard B. Mather, trans., Shi-shuo Hsin-yü: A New Account of Tales of the World, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1976, p.456 (romanisation altered). To this, Mather provides the following footnote: 'Viscaria vulgaris, a medicinal herb in the dianthus family'. [23] Sun Chengtai (孫成泰, zi Xinyi) served as Prefect of Suzhou. [24] We do not know to whom this letter is addressed. Qian Bocheng suggests that it the addressee could have been Chen Suoxue 陳所學, a magistrate of Huizhou, a man who was much fond of talking about xingming 性命 (human nature and destiny). Chen, who became an Advanced Scholar in 1555, was among Yuan's circle of friends. He was the addressee of another letter included in the Deliverance Collection and another one in the Brocade Sails Collection. In a letter addressed to his elder brother, Zongdao, Yuan comments of him that his 'desire to attain the Dao is far too excessive' 道心太甚 (see YHDJJJ, p.492). Yuan Hongdao had also written a preface for Chen's Collection of Intuitions 會心集, a work mainly concerned with literary ideals, for which see Chin-p'ing Chou, Yuan Hung-tao and the Kung-an School, p.52. [25] Wu Guanwo 吳觀我, a late Ming scholar of human nature and principle who advocated the unification of Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism. It seems that Wu's theories on human nature had been a source of inspiration for Yuan. [26] Xuansha 玄沙 was a Chan Buddhist monk from Fujian Province during the Tang Dynasty. He died in 908. [27] Chen Suoxue (陳所學, zi Zhengfu), District Magistrate of Huizhou, Anhui province. [28] Lu Ao 虜敖 was a recluse and wanderer, on whom, see Huainanzi 淮南子, 12:42. [29] Zhao Yingyuan (趙應元, zi Youhe 有鶴; 1531-1584), native of Xinhui county. A Metropolitan Graduate and successful official, Zhao held postings in Sichuan and the Wuxi district of Jiangsu. [30] Shen Fengxiang (沈鳳翔, zi Guangcheng), District Magistrate of Xiaoshan. [31] Xu Dashen (徐大绅, zi Chongbai), then serving as a judge in the Jiaxing prefecture. [32] Wang Zhideng (王穉登, zi Baigu; 1535-1612), a Suzhou native. Famous for his ten-year-old poems, he was good at calligraphy and fond of giving speeches. He was once summoned by the Wanli emperor to serve in the historiographical office but he did not respond to the summons. [33] Qian Xiyan (錢希言, zi Xiangxian), a man from Suzhou. [34] Hua Shibiao (華士標, zi Zhonghan), from Wuxi. Having passed the imperial examinations in the Twentieth Year of the reign of the Wanli emperor (1592), he was appointed to the Board of Punishments. His residence was where Yuan Honghao had stayed during his visit to Wuxi. |