|

||||||||||

|

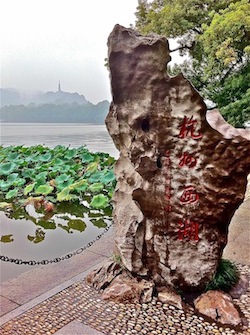

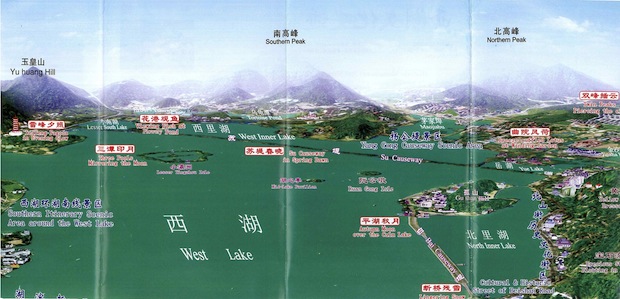

EDITORIALNo. 28, December 2011West Lake 西湖One of the first rhyming Chinoiserie sayings students learn is: 'Above there is Heaven, on earth there are Suzhou and Hangzhou' (Shang you tiantang, Xia you Su Hang 上有天堂,下有蘇杭). These cities with their attendant 'famous sites'—Tiger Hill (Huqiu 虎丘) in the case of Suzhou and West Lake (Xihu 西湖) in Hangzhou—were and are noted not only for their scenery but also because of the skein of historical and literary meaning that embraces, sometimes entangles, them. The art historian Jonathan Hay called Hangzhou and Suzhou two of the 'leisure zones', that is city-scenic areas, in the Lower Yangtze Valley (Jiangnan 江南) where a particular culture of refined indulgence developed around temples, pleasure boats, tea houses, eating places, courtesan's quarters and wine shops.  Fig.1 A designated viewpoint on the eastern bank of West Lake, next to Hupan Ju 湖畔居 teahouse, October 2011. (Photograph: GRB) The depredations of civil war (from the time of the Taiping War in the mid-nineteenth century), foreign rapacity, invasion and revolution (Republican as well as the varied ructions carried out in the name of continuous revolution in the People's Republic) left both cities in grimy decay. In the post-1978 reformist era, mass tourism, guided nostalgia and local identity have helped provide the rationale—and the resources—for both cities to reinvent themselves, and to recall, as well as to exploit, the past. This issue of China Heritage Quarterly takes as its focus West Lake, the defining landscape of Hangzhou, capital of one of China's richest provinces, Zhejiang. As Duncan Campbell, a scholar whose work on West Lake inspired this issue tells us, Hangzhou's West Lake was but one of over thirty identically named sites in dynastic China. It was only from the Tang dynasty (618-907CE) that this particular West Lake gradually displaced all the others and became the West Lake. In the following millennium it evolved into a lieu de mémoire around which poetry, works in prose and latterly painting have continuously produced a layering or sedimentation of meaning, reference, as well as cliché. It is West Lake represented and evoked that at times would seem to obliterate, or at least occlude, its very reality. We approach West Lake anew, not merely as a fabled dynastic 'leisure zone', but more as a place where the pursuit of culture has constantly intermingled with the practice of politics, where the wealth of its denizens has risen and fallen in tandem with the economic strength of Zhejiang and surrounds. It is a place where memory and nostalgia jostle with the lived. While the constructed (and tirelessly reconstructed) past may threaten to constrain the present, still the sheer physical variety and beauty of the Lake and its environs even manage to thwart today's cultural and political engineers. In Features we explore West Lake's physical reality and cultural heritage via various avenues and from different angles, as well as through its changing dynastic, Republican and post-1949 fate. Duncan Campbell locates the lake in a tradition of landscape and introduces the 'Ten Scenes of West Lake' (Xihu Shi Jing 西湖十景), a codification of its scenery that forms a web of poetic, artistic and cultural association. It is through the site-essays of the late-Ming early-Qing writer and historian Zhang Dai—works famous for a unique 'dream nostalgia'—in particular that we encounter at once a place that is a physical reality, a literary realm and a social world. In her work on the West Lake during the reign of the Qing Kangxi emperor, as well as on the early years of the Republic of China, Liping Wang traces the unbroken threads in the fabric of the area as well as discussing the dramatic changes to Qing Hangzhou—the near overnight destruction of the Bannerman Battalion that cut the city proper off from the Lake with which it had so long been associated, and the creation of new commercial and tourist centres. The 'invention' of tradition is a trope that has become popular in international discussions of the past and identity in recent decades, but inventing tradition lies at the very heart of elite Chinese articulations of time. The rediscovery and reformulation of the past is part of a profound movement in cultural practice, one in which renewal is sought through revival or a 'return to the antique' (fu gu 復古). In the revival of West Lake following its less-than-stately neglect during the Cultural Revolution era (c.1964-78), a studied return to the ancient and a manufactured cherishing of the past (huai gu 懷古) have been married to the commercial and political imperatives of the present. At a time in late 2011, early 2012, when the Communist Party re-affirms its half-century opposition to 'the West' and rejection of foreign efforts to undermine Chinese politics and society through a soft-cultural strategy of 'peaceful evolution', we do well to recall that West Lake has, from as early as the Song dynasty, not merely been a place of refined diversion, for it has also been a site of powerful political contestation. The Party's present anti-Western stance was, after all, first articulated half a century ago by Mao Zedong at the Dahua Hotel on West Lake in November 1959. It is important to recall that, during the High Maoist era (mid 1950s to 1976), many momentous political decisions that profoundly affected the country as a whole were made at the lakeside villas and guesthouses of Mao and his comrades. Also in Features we introduce the China Heritage Glossary, an attempt to offer new insights into old words, as well as providing alternative interpretations of new expressions. In T'ien Hsia we carry another chapter from Pierre Ryckmans' (Simon Leys) 1996 Boyer Lectures, this time the subject he address is reading. We also reprint a powerful statement by the novelist Murong Xuecun and pay further tribute to the translator, essayist and novelist Yang Jiang. In Articles we conclude our retrospective on the Xinhai year of 1911 by reproducing an essay on Luo Zhenyu (Lo Chen-yü) and the Waste of Yin, while in New Scholarship we mark the online publication of East Asian History, introduce important new websites, and carry a number of conference and workshop reports. This is the most ambitious issue of the Quarterly to date. Even so much has been overlooked and neglected. We can only hope to expand on this rich and complex topic/trope/topos in future issues. AcknowledgmentsThe scale and range of this issue of China Heritage Quarterly requires that I acknowledge at greater length than usual the contributions of colleagues both locally and internationally. I am particularly grateful to Duncan Campbell, a Contributing Editor of the journal who has helped me conceptualize this issue. Duncan's extraordinarily rich contributions have been crucial both to the style and to content of the issue as a whole. I would also like to thank Mark Elliott of Harvard University for suggesting that I approach Liping Wang, a scholar who has generously allowed us to reprint her work on Republican-era West Lake as well as to carry her new research on the Qing emperor Kangxi and West Lake. Eugene Y. Wang, also of Harvard, has been extremely kind in giving us permission to make available here two of his striking insightful meditations on the Lake, its images and their continuing cultural resonances. Eugene's assistant Jia Yan found time on Christmas Eve 2011 to scan material and search out illustrative materials. One of our young scholars at ANU, Tim Cronin, gave freely of his time to translate Zhou Zuoren's contentious meditation on the 'patriot' Yue Fei and the 'traitor' Qin Gui, which he introduces with considerable flair, and our long-term colleague, the art historian Claire Roberts, has generously allowed us to reproduce a section from a new book on Chinese photography as well as an essay on and an interview with the Hangzhou-trained video artist Yang Fudong. We would also acknowledge the support of Gene Sherman and Dolla Merrillees and the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in granting us permission to reprint this material and the accompanying stills from Yang's work. The noted Hangzhou-based scholar Chen Xing contributed an essay on Feng Zikai, Zheng Zhenduo and West Lake, as well as material related to the revived scholastic journal Aesthetic Education. Other contributors include: Stephen McDowall, Linda Jaivin, Sandrine Catris, David Brophy, Nathan Woolley and Thomas Mullaney. Wang Yaoming and Sang Ye have also provided guidance and advice. As ever, Nancy Chiu has enriched the visual dimension of the journal by helping scan illustrative material and Lois Conner, friend, colleague and long-term collaborator, has been unstinting in her generosity with the work that she has made in Hangzhou and at West Lake since 1984. All have given their time and energy to make this a particularly special issue of China Heritage Quarterly. My Associate Editor, Daniel Sanderson, has laboured long hours over the holiday season. Without his contribution this issue would have remained little more than a fancy. During 2012, China Heritage Quarterly will focus on the following topics: Tea (March); The China Critic (June); Fakes, Phonies and Forgeries (September); and, Nanjing (December). —Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage Quarterly

The Tides of West LakeGeremie R. Barmé

Each time I come, I see something old that is new to my eyes.[1]

Fig.1 West Lake, 1985. (Photograph: Lois Conner)

When China Heritage Quarterly first appeared under the name China Heritage Newsletter in March 2005, we signaled that this publication would advocate a 'New Sinology'. As I have written elsewhere, New Sinology is an academic disposition that commemorates the past endeavors of individuals and broader communities of scholars to understand the complex living heritage of China's past and how it relates to a broader humanity. Located in the present, it is also an attempt to articulate a generous academic approach to China that is ever mindful of the importance of the conditions of historical conciliation (that new-found rapprochement between the dynastic, the Republican, and the People's Republic eras of China), such that from a Western perspective 'China' becomes understood, studied, and appreciated. In brief, New Sinology locates itself inside the Chinese world and seeks to find ways of communicating what makes sense and animates and inspires this world. For this reason, this broad approach is one that emphasizes an attention to detail that will enable the shadows, legacies, ligatures, burdens, possibilities, and constants of China's contending pasts to come to light.[2] Previous issues of China Heritage Quarterly have employed this approach, that is a New Sinology, to focus on the Garden of Perfect Brightness 圓明園, Princely Mansions 王府, Beijing 北京, Tianjin 天津, and Shanghai 上海. In our December 2012 issue, we will turn our attention to Nanjing 南京 and its heritage.  Fig.2 West Lake seen from Hupan Ju 湖畔居 teahouse. (Photograph: Lois Conner) In the meantime, we hope that this issue of the journal focused on West Lake 西湖 will further demonstrate the demeanour with which we engage with and pursue research in the Chinese world. Ours is an engagement that recognizes but seeks to go beyond glib evocations of the past in the present, sly uses of the literary in the vernacular, of traditional folk stories recast for immediate commercial gain, or references to historical personages and incidents that are recalled for ephemeral political advantage. Our effort is to be grounded in the scholarship, Chinese and international, of the past while remaining in vital conversation with the most recent endeavours in various fields. We would argue that, in the same token, it is not enough, or at least not satisfying enough, to apply narrowly modish academic nostrums to a disheveled and unruly reality. Indeed, is it sufficient to impose a presumed order and institutionally sanctioned strictures on matters (subjects, eras, people, events, ideas, practices) that require nuanced appreciation and constant reconsideration? In our own understandings of the living Chinese past—a past that is variously mediated or misrepresented, contested or romanticized, corrupted or carelessly celebrated—appreciating the literature, the language, the learning and the visual dimension, and the manifold interconnectedness of these expressions through the works and lives of individuals, groups and communities allows for expanded possibilities of understanding. The approach we essay in our consideration of West Lake from the earliest times, through dynastic change, republican revolution, the Maoist era and up to the present day is one that reflects the palimpsest nature of lived and living history. It reflects also what Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys) has spoken of as being 'the parallel phenomena of spiritual preservation and material destruction' in Chinese culture; a phenomenon that F.W. Mote casts in the following terms: The point most emphatically is not that China was not obsessed with its past. It studied its past, and drew upon it, using it to design and to maintain its present as has no other civilization. But its ancient cities such as Soochow were 'time free' as purely physical objects. They were repositories of the past in a very special way—they embodied or suggested associations whose value lay elsewhere. The past was a past of words not of stones.[3]  Fig.3 Red Guards at Viewing Fish at Flower Harbour (Huagang Guan Yu 花港觀魚) with the denounced philosopher Ma Yifu's 馬一浮 residence, Jiang Villa 蔣莊, in the background. Our approach is grounded in the written, artistic and imaginative legacies of West Lake. It is one that approaches the subject through essays, scholastic analysis, historiography, translation, pre-modern and modern art (painting, photography, woodblock prints, graphic design, performance art, installations and video art), as well as poetry and social and political history. It is an approach that finds a bulwark against 'a dark future of misunderstanding'. It thus chimes with the prominent classicist Mary Beard's recent observations on the value of the classics in Western culture: [T]he study of the classics is the study of what happens in the gap between antiquity and ourselves. It is not only the dialogue that we have with the culture of the classical world; it is also the dialogue that we have with those who have gone before us who were themselves in dialogue with the classical world… . The second point is the inextricable embeddedness of the classical tradition within Western culture… if we were to amputate the classics from the modern world, it would mean more than closing down some university departments and consigning Latin grammar to the scrap heap. It would mean bleeding wounds in the body of Western culture—and a dark future of misunderstanding.[4] As we have noted in previous issues of this journal the last century has seen various attempts to 'amputate' parts of the Chinese classical world (and not merely state-sanctioned classics) during the country's modern search for meaning, wealth and power. In the late-nineteenth century, following the fall of the Qing, during the New Culture and May Fourth era (1917-27), during the early Maoist years and again in the Cultural Revolution era (1964-78), various cultural amputations created disjunctures that, for a time, would seem to free the present from the burdens of the past. In many cases the delirium of negation served to disguise the ways in which tradition-bound mindsets and practices persisted as their outward manifestations were decried, damaged or obliterated. In the Land of Fish and Rice Fig.4 An overview of West Lake World (Xihu Tiandi 西湖天地) a former walled Party residential island compound. The area was converted into a lakeside tourist zone and opened to the public in 2006. The buildings marked with numbers indicate cafés and restaurants; they were formerly the houses of local provincial and municipal Party leaders. (Photograph: GRB) As the provincial capital of Zhejiang province, Hangzhou played a crucial role in the economic prosperity of Ming and Qing China. Situated strategically in what was famed as the 'land of fish and rice' (yu mi zhi xiang 魚米之鄉), the city was connected to the imperial capital of Beijing via the Grand Canal. Until the mid-nineteenth century this transportation thoroughfare supplied the north with tax grain and official salt from the richly endowed south. Tea, silk and other tributes moved in a constant northward flow. The Canal also connected the city to a vast network of imperial bureaucratic control and inland trade. Bureaucrats and itinerant craftsmen were in ceaseless movement between Hangzhou and the other prosperous mercantile centres of the south, including Suzhou. The artist and writer Feng Zikai 豐子愷 (see 'Drinking by West Lake: Feng Zikai and Zheng Zhenduo' in Features) described the area in the following terms, Along the Grand Canal there were countless inlets and bays, rivulets and passages, and from the air the whole area looked as though a vast fishing net had been cast over the earth, each knot a village or a town.[5] As a major religious destination—its temples and shrines being among the most important in the Lower Yangtze Valley—Hangzhou also attracted waves of pilgrims, from the most humble to the extravagantly wealthy. Their annual inflow to the area is traditionally known as the 'tide of incense' (xiangxun 香汛). For over a millennium the reputation and image of the provincial capital of Zhejiang has been linked with West Lake, a body of water that lies immediately to the west of what, until the 1910s, was the walled city of Hangzhou. The Lake (throughout this issue we also refer to West Lake as 'the Lake') was celebrated as being surrounded by 'misty hills on three sides with a city on the fourth' (san mian yunshan yi mian cheng 三面雲山一面城). It is regarded as one of the most wondrous, and accessible, landscapes in China. Writing forty years ago, the US-based Australian geographer Yi-fu Tuan observed: To the casual visitor the West Lake region may appear to be a striking illustration of how the works of man can blend modestly into the magisterial context of nature. However, the pervasiveness of nature is largely an illusion induced by art. Some of the islands in the lake are man-made. Moreover, the lake itself is artificial and has to be maintained with care.[6] What was created at West Lake—and celebrated through its constant re-creations—was then not merely an 'inscribed landscape' (to use Richard Strassberg's expression)[7] but a landscape that came about in part precisely because of inscription. West Lake was and remains a landscape that is literally 'cultivated' or made by scholar-bureaucrats and garden/city planners who at the same time as shaping nature through dredging, the planting of trees, building and civic projects also extolled their artifice by naming it, writing about it and depicting it in works of art. The landscape of West Lake then is as much man-made as natural; man-made not only in the physical sense, but also as an environment bound in the cultural and historical warp and woof of stories, personages, fables, poems and art works. Today statues, former residences, commemorative buildings, tombs, statues, wall plaques and museums dot the Lake in a crisscross of historical reference. They provide an itinerary of cultural meaning that embraces everything from the lyrical to the revolutionary. The use of historical figures, or stories from the past, or indeed from fiction, to support the regnant authority—be it dynastic, Republican or contemporary, is a crucially important feature of what is today dubbed the 'humanistic' or rather 'humanities encoded' topography (renwen jingguan 人文景觀) of the Lake. Decline & Prosperity Fig.5 Looking towards West Lake World, and a Starbucks outlet, from what was Yongjin Gate 湧金門. (Photograph: GRB)

My first encounter with West Lake came in the dying days of the Cultural Revolution. I was part of a small band of foreign students studying at Liaoning University in Shenyang (瀋陽遼寧大學) that, during the Spring Festival break of 1976, was organized to travel 'within the pass' (guannei 關內) as the local cadres put it to enjoy the milder weather of the south. Hangzhou and West Lake were on the itinerary. We stayed at the Hangzhou Hotel, a stolid Sino-Soviet structure dating from the mid 1950s that was located on the north shore of West Lake (since 1984 the luxuriously remodeled complex has been part of the Singapore Shangrila chain of hotels). In those days, the nearby Yue Fei Temple 岳王廟 had been cut off from the Lake by various low-rise structures; the once famous grave of the courtesan Su Xiaoxiao 蘇小小之墓 had long been demolished, as had the commemorative mound that celebrated the fictional hero Wu Song 武松墓. Nor was there a statue to celebrate the late-traditional painter Huang Binhong 黃賓鴻 and his important artistic contribution to the cultural life of West Lake. His reputation was under a cloud and few knew of him. The Su Causeway 蘇堤 that stretched out in front of the hotel had been neglected for many years and Chang Mansion (Chang Zhai 常宅), nearby the northernmost end of the causeway, was occupied by the People's Police. What would be revived much later 'Breeze Amongst the Lotuses of Brewing Courtyard' (Quyuan Fenghe 麴院風荷), one of famous Ten Scenes of West Lake, was home to a poultry and duck farm. The quiet desolation of the Lake, a sombre mood that persisted through most of the 1980s, made it easier to appreciate the limpid register of the late-Ming essayist Zhang Dai's 張岱 accounts of a lost world of delicate pleasure and boisterous diversion. And it was in the late 1970s, as West Lake began it thirty-year recovery from the Maoist era, that Zhang's works began to be republished, along with a small number of collections of poetry and prose related to the Lake. These literary artifacts resurfaced in tandem with the fitful rebirth of cultural recreation on the Lake, and just as plans were being mooted by the Hangzhou authorities to revitalize a place that had fallen once more into ruin due to the vicissitudes of politics.  Fig.7 West Lake and the city of Hangzhou at night

At the time it was still hard to imagine that the Lake had been part of the cultural epicentre of the highly productive, economically wealthy and sybaritic heartland of China's Lower Yangtze Valley 'land of fish and rice'. Nor did I realize that the disheveled state of West Lake in the 1970s was as integral to the cycle of decline and renewal that like the tides of the nearby Qiantang River, or the swelling and falling away of the waters of the Lake itself were a feature of its history for over a millennium. Yi-fu Tuan has noted that the landscape of the Lake requires careful maintenance; equally, its despoliation is the result of human purpose. In this issue we recall You Tong's 优同 despair at the neglect of the Lake in the early Qing period as featured in the work of Liping Wang; the sepia scenes of decay dating from the early Republic as discussed by Eugene Wang; and the 'morbid prosperity' of the Lake in the late Republic as noted by James Gao. Continuing our interest in the 'prosperous age' (shengshi 盛世) that was the focus of the June 2011 issue of China Heritage Quarterly, in this issue we also consider the lake-garden of West Lake in the context the cycle of prosperity and decline, fruition and decay, and how these too are central concerns in Chinese articulations of time, political power, economic weal and bane and shifting cultural moods. A Poet and Her FatherOne of the many literary figures who lived and wrote near West Lake is Li Qingzhao (李清照, 1084-ca.1151), a poet from the Southern Song. Today she is commemorated for her ci-lyrics. When the environs of West Lake were being made over in the first decade of the new millennium a small commemorative structure was built to honour her memory. Li's most famous poem is inscribed on the building's wall. When he visited the site in 2003 shortly after handing over power to the next generation of party-state leaders, the former Communist Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin 江澤民 turned his back to the wall and proudly recited the poem from memory:

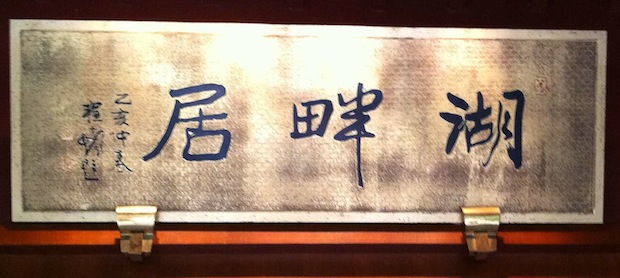

Fig.8 A calligraphic inscription over the entrance of the Hupan Ju teahouse, the lakeside site where key meetings were held to discuss the replanning of West Lake and its environs in the early 2000s. Jiang then told the local officials accompanying him that Li Qingzhao was 'a great Chinese poet with an outstanding literary reputation'; he instructed them to 'step up propaganda work [in relation to her] so as to enhance her influence.'[9] Perhaps these seemingly inapposite remarks reflected Jiang's own melancholic mood and a recent bout of 'relevance deprivation syndrome'. As a native of the nearby city of Yangzhou, which itself is famous for its 'Slender West Lake' (Shou Xihu 瘦西湖), and self-styled as a man more familiar with traditional culture than either his post-Mao predecessors or his successor, Hu Jintao 胡錦濤, Jiang Zemin would have also been aware of Li Qingzhao's father, Li Gefei (李格非, ca.1045-1105). Li's record of the gardens of the northern dynastic capital of Luoyang 洛陽 is the first substantial work of its kind. In the introduction to his account of that city Li makes a statement that has resonated ever since: The prosperity or decline of Luoyang can foretell whether the world itself enjoys stable rule or chaos; so too the prosperity or decline of Luoyang can be discerned by the flourishing and decay of its gardens.[10] One could argue that, since the end of the Ming dynasty in the 1640s, the prosperity and decline of West Lake has reflected the waxing and waning fortunes of both Zhejiang and the Chinese world. The Lake Viewing Pavilion Fig.9 A stone engraved with the signatures of party-state leaders who have frequented Wang Villa, West Lake, October 2011. (Photograph: GRB)

In the first post-Mao decade it was generally a matter of speculation as to what went on at the vast swaths of property on the western and southern banks of the Lake marked off as restricted zones. Access was denied by guarded gateways and patrolled jetties and wharfs were the only evidence of West Lake's hidden life. Only gradually did it became common knowledge that these heavily wooded preserves and walled compounds were the grounds of villas commandeered by Party leaders from the 1950s. Before Mao Zedong's favourite residences—Liu Villa 劉莊 and Wang Villa 汪莊—were opened to the public, or at least to well-heeled tourists,[11] I had an encounter with the de-commissioned Hangzhou residence of the disgraced Marshall Lin Biao 林彪. It was 1983 and a friend was working on biopic of Liao Zhongkai 廖仲愷, a close associate of Sun Yat-sen 孫中山. The film was being directed by the veteran film-maker Tang Xiaodan 湯曉丹 and the crew from the Pearl River Film Studio in Guangzhou 廣州珠江電影製片廠 was being housed in a massive building with a bunker and metre-thick walls situated to the west of the Lake itself on what is now Master Yang's Causeway 楊公堤. This was formerly known as 'Project 704'; it was now part of the Zhejiang Hotel (Zhejiang Binguan 浙江賓館) complex.[12] As the Communist past was fitfully, and even then only partially, revealed, far more was coming to light regarding the pre-revolutionary life of West Lake. It is a life revealed by the republication of late-Ming essays, works from the Republican era, and accounts of the Qing imperial obsession with West Lake, in particular those that reflected how the emperors Kangxi 康熙, Yongzheng 雍正 and Qianlong 乾隆 had scenes from West Lake (which they had themselves helped create) replicated in their northern gardens, both near Beijing and beyond the Great Wall at Jehol (Re He 熱河). During the era of rehabilitation that was the 1980s, I met local Hangzhou scholars like Chen Xing 陳星, China's leading specialist on the work of Feng Zikai and the life of Master Hongyi 弘一法師, both of whom were closely associated with West Lake. And through Chen Xing I came to know the local novelist like Li Hangyu 李杭育. While my interest in contemporary art eventually brought me into contact with the artists Zhang Peili 张培力, Geng Jianyi 耿建翌 and Wang Qiang 王强, as well as with their Pond Society (Chi She 池社).  Fig.10 Tourist map of West Lake today

In the 1980s, Chen Xing helped guide my appreciation of Feng, Li Shutong 李叔同 and also the philosopher Ma Yifu 馬一浮, whose own lakeside Jiang Villa 蔣莊, was eventually opened to the public. Chen and I frequented spots on the Lake, and as soon as it was rebuilt in the late 1980s we took to meeting at the Lake Viewing Pavilion (Wanghu Lou 望湖樓) on the northwest shore to drink heated Shaoxing wine (huangjiu 黄酒) and snack on dried beancurd (doufugan 豆腐干), the Lake never far from view or from our conversation. This pavilion was supposedly on the site described by one of the Song scholar-bureaucrat Su Shi's 蘇軾 many poems about West Lake:

As I wrote about Feng Zikai, and eventually produced a book on his life and work, West Lake remained a constant interest. For some time I wanted in particular to write a short piece related to Feng Zikai's encounter with the Tidal Bore of the Qiantang River near Hangzhou. Now, after nearly thirty years, I have finally written that essay (see 'The Tide of Revolution' in Features). Although one of Feng's mentors, the educator Jing Hengyi 經亨已 makes an appearance in it, Zikai does not. With easy access to West Lake in the 1980s, and with the ready availability of new works on Zhang Dai and other late-Ming writers I thought of undertaking research on the Lake. But from the late 1970s my reading had led me to Feng Zikai and more contemporary cultural dilemmas; I had also learned that Duncan Campbell, a friend whom I first met as a student, was translating Zhang Dai's writings about West Lake. It is Duncan then who has been the immediate inspiration of the present issue of China Heritage Quarterly. His work on the Ten Scenes of West Lake and his translations of Zhang Dai's poems and selections from Search for West Lake in My Dreams (Xihu mengxun 西湖夢尋) provide us entrée into the complex history, culture and politics of the Lake. Garden Living Fig.11 A stele at Liu Villa marking a spot where Mao Zedong studied English Much writing on West Lake reflect not only the changing seasons and moods of the place, but also the constant interplay between human industry (recalling Yi-fu Tuan) and natural phenomena. The rhythms of the seasons and the unsteady fluctuations of temporal power have been a central concern of Chinese historians, litterateurs and artists from long before the modern era. The natural world and the garden—that cultivated space that reflects, mimics and enhances nature—have provide both a metaphorical landscape and a language for the discussion and understanding of human affairs. The creation of gardens (xiu yuan 修園) and living in gardens, or being 'sequestered in a garden' (yuan ju 園居) have been favoured by the leisured as well as the powerful for centuries. The making of sequestered spaces and indulgence in their rarified luxuries have been a source of frequent tension for rulers—while desiring their paradisiacal retreats they have been sorely aware of the frugality expected of them. It is little wonder then that in the Communist era the exclusive gardens-residences of Mao Zedong and his colleagues were carefully hidden from public view, on the grounds of 'state security', of course. These secret gardens were in many instances the real sites of power during the Maoist era, just as they garden-palaces were often the loci of politics during the Qing dynasty. Vast sequestered residences were a luxury for Party leaders even if the relative restraint required by official philosophy (not to mention party-state impoverishment) meant that there was a limit to their extravagance. Nonetheless, traditional concerns about rulers being seen, even by their fellows and their staff, as indulging themselves were coupled with an avowed ideology of proletarian frugality. West Lake then was figured as being a place of dedicated political work that was far from the quotidian distractions of the capital in the north. Even if Mao increasingly 'enjoyed the mountains and waters' (you shan wan shui 游山玩水) he shared concerns expressed by the late-imperial rulers Kangxi and Qianlong during their garden residencies or Tours of the South 南巡 that relaxation and the pursuit of literary interests were but peripheral to matters of empire. Periods at West Lake were part of a sacrosanct activity covered by the nebulous term 'the necessities of work' (gongzuo xuyao 工作需要). A Partial PoliticsAs we repeatedly observe in this issue of China Heritage Quarterly politics, culture and power have been manifest at West Lake from the time that the Song court fled south following the Jin 金 invasion to set up a temporary capital at Hangzhou, which they renamed 'Lin'an' (Lin'an 臨安), 'temporary refuge'. General Yue Fei 岳飛 bristled at the suggestion that the Song had to be satisfied with an empire thus reduced and forced to 'survive on limited territory' (pian'an 偏安). He derided this expression, one that dated back to the Han dynasty, but he eventually fell victim to his 'patriotic' ambition to lead the Song retake its lost northern territories. No such illusions exist for those who have used the term pian'an 偏安 in recent times. And it is noteworthy that this formulation appeared in Chinese political discussions again in January 2011. It came during the celebrations of the centenary of the Xinhai revolution when the Nationalist Party President Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九 declared that while the Republic of China would embrace 'the cultural Sinosphere' (wenhua Zhonghua 文化中華), it recognized a status quo that required it to 'survive politically on limited territory' (zhengzhi pian'an 政治偏安), that is on the island of Taiwan.[13] As Duncan Campbell tells us, over the centuries there have been many West Lakes. Today, the Slender West Lake of Yangzhou (Shou Xihu 瘦西湖) is still celebrated, while to the far east Tokyo still boasts of its own West Lake at Ueno 上野: Shinobazu Lake (Shinobazu no Ike 不忍池).[14] In our consideration of West Lake at Hangzhou we concentrate in particular on that gap between West Lake in the past (from the Tang dynasty) and the present age, and we consider some of the writers who through their prose, poetry and history writing have themselves approached the gap between their times and the ages before them. This issue attempts to present a layering of texts, images and ideas in imitation of the sediments of West Lake itself, as well as the culturally inscribed landscape of the Lake and its surrounding hills. The material is arranged in a roughly chronological fashion, but many of the articles, essays, translations and images refer to scenes, features and personalities that weave through time and this skein of reference and allusion creates, we hope, is a sense of the fabric meaning in which West Lake exists, and indeed is enwrapped.  Fig.12 Lamp-post advertisement for 'Impression—West Lake' 印象·西湖, Zhang Yimou's song-and-dance extravaganza at Nanshan Road 南山路, West Lake. (Photograph: GRB) Today's West Lake and its UNESCO heritage-listed environs celebrate an idealized cultural environment. However, as we have argued, it is the changing mien of the Lake that is central to its history, its natural forms and its cultivated sights. With time, politics, economics, climate change and human action, the Lake has risen and fallen both in physical terms and in the Chinese mind. Contemporary practice—with all of its heritage, tourist, economic and cultural concerns—requires perhaps that West Lake be frozen not only in time but also in significance. The Lake might be a comfortable and reassuring museum, but is this latest state-funded incursion in its life more about stasis than change, more concerned with fixity than with the natural (or at least fluctuating human) flow of things? For the West Lake of China's contemporary party-state not only has the detritus of decline and Maoist politics been swept away, much more has been eliminated in the pursuit of an ideal, accepted and 'harmonious' Lake.[15] Apart from a public notice and an extant poem in Qianlong's hand, the Qing-era Bannerman history of Hangzhou has been obliterated. Similarly, the long years of Japanese occupation in the 1930s and 40s is invisible. Lakeside villas carry only vague references to the late-Qing or the Nationalist periods. Even Chiang Kai-shek 蔣介石 and Soong Mei-ling's 宋美齡 lakeside villa, Cheng Lu 澄廬, is barely mentioned. The early Communist Party occupation of Hangzhou is presented in a glaringly positive light; meanwhile, the tireless plots and counterplots launched at Hangzhou by Mao and his fellows in their secret gardens are all but impossible to discern. Equally elided is the history and impact of the Anti-Rightist purges of intellectuals and workers or the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s and early 60s. The sufferings of internal refugees, the pangs of the hungry, the straits of the destitute and persecuted—none of this feature in a landscape where ancient patriots and progressive activists alone are commemorated. And of the Cultural Revolution, a period when Hangzhou was a hotbed of rebellious foment throwing up the worker-rebel Weng Senhe 翁森鹤, there is no sign. Forgotten too is the fact that Hangzhou was a site of some of the most violent factional fighting in the last years of Mao's life, even at the time when he was recuperating from eye surgery at Wang Villa in 1975. There is a great centrifugal attraction among literate Chinese in a West Lake that is rich in symbolism and abstraction. There is an imperceptible evacuation of social memory; in its place what remains are the 'solitary pride' and 'vacuous reputations' of talented scholars and hermits buried in the charming hills and waters. Genius and frustration of grand proportions are reduced to become scenic sights for casual visitors. Sight and more sights; always sights. So writes the essayist Yu Qiuyu 余秋雨, himself a literary figure around whom controversy regarding his own checkered political past continues. Nonetheless, he offers a view of how much of the complexity of West Lake is today reduced to formalized 'scenes' presented for the diversion and pleasure of tourists. The authorities celebrate the place as providing a landscape that is sculpted to allow only for the politically approved admiration of 'loyal ministers and people of righteousness' (zhongchen yishi 忠臣義士). West Lake is a guilt-free environment. Perhaps this is an aspect of West Lake that attracted not only two of the Three Great Emperors of the Qing era, but also three prominent leaders of the modern era: Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong. West Lake continues to entice and garner approval from China's post-Mao leaders. Time and TideIn West Lake alone has Heaven produced a valley that is neither too distant nor too close at hand, neither too shallow nor too deep. It is a place that can be visited either at the break of dawn or at the closing of day; a place where one may sit or be in repose, where the mist on the hills and the ripples over the water extend as far as the eye can see, yet pose no danger. At West Lake one may stroll about as one pleases yet not tire; it is a place where even years of exploration will never exhaust the delights hidden there, but one also where a single day's pleasure may satisfy boundless craving. —Wen Qixiang 聞啟祥, 'West Lake Boat Society' (Xihu chuanhui 西湖船會)[17] Fig.13 The Pavilion of Wind on the Waves (Fengbo Ting 風波亭), West Lake, at sunset. (Photograph: GRB)

It is not only in recuperation of artistic images or poetic lines that the reality of West Lake has been transformed. Years of debate, thought and planning have worked to create the multivalent Lake of today. It is hardly an ideal space—the electric tourist buses that constantly circle the inner lake (it is an hour-long trip) with their cheerfully annoying horns make lakeside strolls possible and trouble free only in the early hours after the break of dawn, or evening. At least retail outlets are fixed and entrance fees to the interconnected parks on the eastern shore, as well as those along the Su Causeway, have been abolished. Gone too are the garish neon lights of the 1990s; although the evening quiet of the Lake is now marred by the balletic water fountains (yinyue penquan 音樂噴泉) on the eastern shore and the rude clamour of the Zhang Yimou 張藝謀 'Impression—West Lake' 印象·西湖 song-and-dance extravaganza to the northwest near the Yue Fei Temple. But with the ebb and tide of political and cultural fashion, these too will daresay give way to a future Lake in which the past can always be dredged up.

Notes:[1] R.J.B. Bosworth, Whispering City: Rome and its Histories, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2011, p.xvi. When strolling near the Colosseum in Rome in 1970s, Bosworth encounters a Jewish stranger who remarks, 'I have come every year since Fascism fell. Each time I come, I see something old that is new to my eyes.' [2] See my review essay of Paul A. Cohen, Speaking to History: The Story of King Goujian in Twentieth Century China, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008, in The Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 71.2 (December 2011): 351-64. [3] This quotation from F.W. Mote can be found in the Postscript to Pierre Ryckmans, 'The Chinese Attitude Towards the Past', the Forty-seventh George E. Morrison Lecture, 16 July 1986, The Australian National University, online, at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=014_chineseAttitude.inc&issue=014. The quotation from Ryckmans also comes from this lecture. [4] Mary Beard, 'Do the Classics Have a Future?', 12 January 2012, online at: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/jan/12/do-classics-have-future/. [5] Quoted in translation in Geremie R. Barmé, An Artistic Exile, a life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975), Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, p.15. In the minds of the elite, and possibly the popular imagination, although that is more difficult to gauge, the Lower Yangtze Valley, Jiangnan, was also represented by a number of places of leisure and memory—Qinhuai in Nanjing, Tiger Hill in Suzhou and West Lake in Hangzhou. See Jonathan Hay, 'The Leisure Zone: Depictions of the Sub-urban Landscapes of Seventeenth-Century Jiangnan', pp.3 & 5, referred to in Tobie Meyer-Fong, Building Culture in Early Qing Yangzhou, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003, p.134. [6] Yi-fu Tuan, Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1974, p.133, quoted in Duncan Campbell, 'The Ten Scenes of West Lake' in this issue, at: http://newrspas.anu.edu.au/pah/chinaheritageproject/newsletter/features.php?searchterm=028_scenes.inc&issue=028. [7] See Richard E. Strassberg, Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994, pp.5-7ff. [8] Stephen Owen, ed. and trans, An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, New York and London: W.W. Norton, 1996, p.581. [9] My translation. See also Stanislaus Fung's translation in 'Longing and Belonging in Chinese Garden History', Michel Conan, ed., Perspectives on Garden Histories,Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library & Collection, 1999, p.216, referred to in Duncan Campbell's rendering of Zhang Dai essay on Liuzhou Pavilion (Liuzhou Ting 柳洲亭), note 50, in this issue. [10] Zhang Jianting 张建庭, 'Thirty Years on Hangzhou's West Lake: Deputy-Mayor Zhang Jianting Looks Back on the Development and Protection of West Lake' (Zhang Jingting fushizhang guanyu Xihu fazhan he baohude huigu 杭州西湖三十年: 张建庭副市长关于西湖发展和保护的回顾), a speech as recorded by Yan Ge 嚴格 and Gu Qizheng 古其錚. [11] See my essay 'Mao Zedong's West Lake: The Revolutionary Retreats Liu Villa 劉莊 and Wang Villa 汪莊' in this issue. Mao's principal West Lake residence, Liu Villa, incorporated five disparate private residences acquired by the Party authorities in the early 1950s. These were Liu Villa 劉莊, Han Villa 韓莊, Yang Villa 楊莊, Kang Villa 康莊 and Fan Villa 范莊. Extensive reconstruction of the main lakeside residence of the old Liu Villa under the direction of Zhang Nianci 張念慈 began in January 1959 at the time of the calamitous Great Leap Forward. In keeping with early Communist era practice it was dubbed 'Project 5901' (5901 gongcheng 五九0一工程). Four clusters of buildings were designed and designated using a traditional form of numeration as Jia, Yi, Bing, Ding 甲乙丙丁. Mao's family compound, the Jiabu 甲部, contained sleeping and living quarters, a meeting room and a dining hall. Yibu 乙部 consisted of a ping-pong room and a movie theatre for Mao's wife, Jiang Qing 江青. These two clusters were joined by covered walkways and separated by a bamboo garden in keeping with the style of the original Liu Villa, which had been built by a Cantonese merchant who had a large bamboo garden planted there. Zhang Nianci included various other modernized traditional features in the design of the buildings, their roofs and their decoration. (For these details, see 'Liu Villa' in Zhang Jianting 張建庭 and Zhong Xiangping 仲向平, Villas Around West Lake (Xihu Bieshu 西湖別墅), Hangzhou: Hangzhou Chubanshe, 2005, pp.81-83.) Here we should note that Mao was no means a sedentary leader. Although he by no means 'ruled from horseback'—as his famous predecessors in the High Qing were famed to have done—travelling constantly by train on provincial and city tours of inspection (xunshi 巡視and shicha 視察), staying in his favourite redoubts, he was very much a peripatetic ruler. [12] An unimpressive wall and featureless gate disguised this high security compound—just as the rather simple entrance to Mao Zedong's favourite Liu Villa was an act of frugal dissemblance. 'Project 704' (704 gongcheng 七0四工程) was so named as construction work started in April (the fourth month) of 1970. It consisted of four stolid one-storey Cultural-Revolution-style buildings. They were connected by underground passages, with elevator access to the bunkers in Lin's building alone. A similar maze-like underground command centre, Building No. 7 (Qihao lou 七號樓), was constructed for the Marshall at an existing building at South Garden (Nan Yuan 南園) in Suzhou. The tunnels and garage with what is signposted as Lin's Red Flag limousine are on display. It was supposedly in Suzhou that Lin planned his armed uprising against Mao under the codename of 'Project 571' (517 Gongcheng 五七一工程). Lin, who fell from grace, literally and metaphorically, in September 1971, has been disparaged since his death and the residences he used or had built for his use outside Beijing are invariably described as being 'detached palaces' (xinggong 行宫). [13] See: http://www.chinareviewnews.com/doc/1015/6/6/2/101566276.html?coluid=7&kindid=0&docid=101566276 [14] Jin Wenjing 金文京, 'West Lake in Japan and Korea—comments on the literary significance of the transposition of landscape in East Asia' (Xihu zai Ri Han—lüetan fengjing zhuanyi zai dongya wenxuezhongde yiyi 西湖在日韓——略談風景轉移在東亞文學中的意義), 'Dongya wenhua yixiang zhi xingsu' xilie yanjiang—Jin Wenjing jiaoshou (30 July 2008). [16] The approved narrative for West Lake today is available in a handy volume edited by Qian Jun 錢鈞 under the title Tour Guide Narrative of All Sights of the New West Lake (Xin Xihu quanjing daoyouci 新西湖全景導遊詞), Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 2005. [17] From Yu Qiuyu 余秋雨, 'West Lake Dream' (Xihu meng 西湖夢), online, at: http://www.ccview.net/htm/xiandai/wen/yuqiuyu015.htm [17] Translated by Duncan Campbell from Wen Qixiang (fl.1612-40), Drafts from the Studio for Delighting Oneself (Ziyuzhai gao 自娛齋稿). As Duncan notes, this translation is based on the text given in Zhou Zuoren 周作人, ed., A Collection of Essays by Ming Writers (Ming ren xiaopin ji 明人小品集), Taipei: Jinfeng, 1987, p.63. For a biography of Wen Qixiang, see Qian Qianyi 錢謙益, 'Tomb Inscription for Wen Qixiang' (Wen Zijiang muzhiming 聞子將墓誌銘), in Qian's Qian Muzhai quanji 錢牧齋全集, Shanghai: Guji Chubanshe, 2003, vol.2, pp.1364-66. |