—Italo Calvino,

Invisible Cities (1997)

Finding myself back in Peking for several weeks two years ago, some few months before the city celebrated the opening of its Olympic Games ('the biggest and the best') and feeling somewhat dislocated by the scale of the changes wrought on the city in anticipation of that event, I spent a day searching for the former residence of the city's greatest traditional historian, Zhu Yizun 朱彝尊 (1629-1709),[1] in the hope that it might help reorient me in a city that I had once felt I knew so well.

A useful little book that I had come across in a bookshop in Haidian 海淀 a day or so earlier, a guide to China's house museums and ancestral temples, provided both an address (Haibai Hutong 海柏衚衕)[2] and a short description of the house:

…a small building in the southern section of the Shunde County Lodge (Shunde Huiguan 順德會館).[3] Zhu's Pavilion for Airing My Books (Pushu Ting 曝書亭) once stood in front of his residence, this having since been dismantled, although two ancient wisteria vines remain, both of which are several hundreds of years old and the scent of which, in early spring, proves quite overwhelming.

This source also indicated that it was now a house museum administered by the municipal authorities.[4]

Zhu Yizun was a man I had long been interested in. One of the greatest book collectors of his age, the circumstances of his removal to this particular residence—he was a native of Xiushui 秀水 (present-day Jiaxing 嘉興) in Zhejiang but had spent many long years in Peking—were both unusual and illustrative, I thought, of larger themes to do with the obstacles to access to books and the circulation of knowledge in the late-imperial period. After his success in the special examinations of 1679, Zhu had been appointed to the Hanlin Academy with concurrent editorial responsibility for the compilation of the official history of the Ming dynasty and the gazetteer of the empire, having also been granted (on the Second Day of the Second Month of 1684) a residence by the Kangxi emperor (r.1662-1722) himself, within the walls of the Imperial City and just to the north of Coal Mountain. Dismissed—called by his contemporaries a 'beautiful demotion' (meibian 美貶—from office for having unauthorized copies of materials held in the imperial collection made, Zhu was also banished to the Outer or Chinese City, to the Xuannan 宣南 area, south of the Gate of the Promulgation of Martial Power (Xuanwumen 宣武門).

Having been thus removed, Zhu Yizun immediately marked his sense of dislocation with a poem:

On Moving from the Forbidden City to Live Beyond the Walls

Permitted to move my household goods,

My books however find no fixed abode.

Who now pities me for the loss of my spring dream,

As I listen to the bell ringing from beyond the walls?[5]

Whether because of a longstanding interest in the history of the city or by virtue of his present enforced close proximity to the celebrated secondhand and antiques markets of Lilichang 琉璃厰, Zhu spent his years of exile engaged in a number of large bibliographical projects. One such project was his monumental documentary history of the city, entitled Accounts of the Past Heard in the Precincts of the Sun (Rixia jiuwen 日下舊聞). In his 'Preface' to the work, dated 1688 and translated below, Zhu Yizun had captured for all time something of the essential melancholy of a city that, in keeping with its role throughout the late-imperial period of China's history, seems always to have been particularly prone to the vicissitudes of history:

The present Imperial Capital [Jingshi 京師] was chosen by Fan Zhen 范鎮 in consideration of the great expanse of the site, lending it a sense of openness and of height, its flatness also serving towards the straightness of the lines of the city. Liang Xiang 梁襄 said of it that, 'To the north, it trusts to the protection afforded by mountain fastnesses, to the south it maintains order over the entirety of the Chinese empire.' Truly then, it is a site that is the worthy foundation of an August Enterprise, an ideal place for the establishment of a Capital City [Jingdu 京都].

Once the Yellow Emperor had established his settlement on the banks of the Zhuolu 涿鹿 River, the Zhou imperial house enfeoffed the place as the territory of Reeds [Ji 薊]; later the Northern Yan made it their capital. The Murong Yan continued its role as capital and under the Khitan Tartar Liao [907-1115] the city was known as the Southern Capital [Nanjing 南京]. Under the Jurchen Jin [1115-1260], it was known as the Middle Capital [Zhongdu 中都], whereas under the Mongol Yuan [1260-1368] it became the Great Capital [Dadu 大都], and then under the Ming [1368-1644], the Northern Capital [Beijing 北京], a name continued by this present imperial dynasty, in order to give expression of its control over the ten-thousand nations. So numerous and splendid are the city's palaces and halls, wells and townships, so full and well-stocked are its granaries and its treasuries, that this surely is what is referred to in those lines from the Book of Odes [Shi jing 詩經]:

The capital of the Shang was full of order,

The model for all parts of the kingdom.[6]

Examining the various records, one finds that half of Tranquillity Prefecture [Youzhou 幽州] under the Tang dynasty lay to the west of the present-day new city, and that the Jin had expanded their town southwards, whereas the Yuan had opened up the northeast of the city. Once Xu Da 徐達 [1332-1385] had established the city as the Pacified North [Beiping 北平], he razed to the ground the old city, constructing in its place a smaller new city, with the temples of Vast Heaven [Haotian Si 昊天寺], Pity for Loyalty [Minzhong Si 憫忠寺], Extended Longevity [Yanshou Si 延壽寺], Bamboo Forest [Zhulin Si 竹林寺], and Dew of the Immortals [Xianlu Si 仙露寺] all delimited as being beyond the city walls, with gates such as Resplendent Prosperity [Guangximen 光熙門] and Established Uprightness [Anzhenmen 安貞門] and others having been destroyed. When the Jiaqing Emperor [r.1522-66] began constructing his new city, all these temples were once again to be found within the city walls, whereas the area to the left of the Liang Garden 梁園, all the way down south until Wei Village and to the east until the Divine Timber Factory, remained, as before, beyond the suburbs of the city. As to the palaces and gates of the Yuan city, in terms of their positioning, these would have been found to the north of the present-day Gate of Fixed Peace [Andingmen 安定門].

At the beginning of the Ming, when the former palaces of the south of the city were rebuilt as the residence of the Prince of Yan, the pattern followed in their design was not that of the Great Capital of old. Alas, the sites of the palaces and mansions, the walls and the marketplaces change repeatedly, and only one in ten of the monasteries and temples are found where they once stood, and nine out of ten of these now bear different plaques. As that which once was there is ruined and disappears, and even the books recording their former existence become scattered and lost, as the years follow each other, one after another, the physical traces of the past will become ever harder to seek out.

Finding myself at something of a loose end after I had been dismissed from office, I resolved to gather together into a digest all the text found either in the written records or inscribed on stone and bronze, dividing the material into twelve categories, with a supplementary category tagged on, as follows:

1. The Stars and the Soil (Xingtu 星土)

2. Chronological Records (Shiji 世紀)

3. Natural Barriers (Xingsheng 形勝)

4. Palaces and Mansions (Gongshi 宮室)

5. Walls and Marketplaces (Chengshi 城市)

6. The Suburbs (Jiaojiong 郊坰)

7. The Capital Domains (Jingji 京畿)

8. Administered Territories (Qiaozhi 橋治)

9. Border Defences (Bianzhang 邊障)

10. Population Registration (Huban 戶版)

11. Customs and Habits (Fengsu 風俗)

12. Products (Wuchan 物產)

13. Miscellaneous Descriptions (Zazhui 雜綴)

In total, my book comprised of forty-two juan. When the Minister of Justice, Xu Qianxue 徐乾學 [1631-94] of Kunshan,[7] happened to catch sight of it, he declared that it was worthy of being transmitted, promptly offering funds for the cutting of woodblocks. The draft of the book was compiled over the summer of the Bingyin year [1686], the work on gathering the materials was completed by the autumn of the Dingmao [1687] year, the printing of it commencing in the winter of that year, the book having been completed in the Ninth Month of the succeeding Wuchen year.

Many are its lacunae, and I am mortified every time I read through it, commanding my son Kuntian 昆田 to oblige me by seeking to make up the gaps in the record and to add these as supplements to each juan of the book. A total of more than 1600 books have been consulted in the course of compiling this work and because I am worried lest readers of my book will not recognise where many of these extracts come from, in each case I have made note of the source at the end of the extract, not simply in order to make a display of the wideness of the net I have cast in search of relevant material. Long ago, in the process of compiling his Collected Commentaries on the Record of the Rites (Li ji jishuo 禮記集說), Wei Zhengshu 衛正叔 employed the practice of his contemporary Confucian scholars of appropriating the words of those who had come before and claiming them as there own, saying to all who would listen that their sole concern was that the products of the hand's of others would not be regarded as their own. I, for my part, am concerned only that this compilation of mine not be considered the product of others. Being myself a dull-minded man, I have adopted Wei Zhengshu's procedure here. As to materials that derive from works of unofficial history or fiction or from the two schools of fortune telling, much of which may perhaps not be fully believed, I would be fortunate indeed if my dear readers do not accuse me of being imprecise in my selection of text to be included in this present work!

A colophon to Zhu's history of the city provides a charming vignette of the author at work. His friend Wang Yuan 王原 wrote:

Once the Master was no longer in service, he rented lodgings beyond the Gate of the Promulgation of Martial Power, and there he would sleep and work within a single room, night and day, with a rattan bed and a bamboo desk his companions, surrounded to left and right by shelves stacked with the ten thousand volumes of his library. His eyes would be forever reading and his hands were never without a book. Frequently he would entertain men of earlier ages in order to tax them for the details of long-forgotten anecdotes of the past, or go off to take a rubbing from some half-forgotten stele, venturing along dangerous cliffs and braving swift rivers in this quest, heedless of twisted angles and calloused feet.

Others in their prefaces to the work drew parallels between Zhu Yizun's work and earlier historical guides to capital cities. In his preface, for instance, Gao Shiqi 高士奇 (1645-1703), himself the author of a book on the Forbidden City, writes:

No important aspect of the city is ignored, no detail proves too minor, and yet, disavowing any claim to authorship, Zhu Yizun says that all he has done is to transmit that which he had heard tell of the city. Having encountered in his life a prosperous age, Zhu Yizun amused himself with this compilation, thus giving rise to an immortal work, worthy of being placed on the mountain of fame. This work, upon examination, proves far superior to such books as the Yellow Plans of the Three Capital Commanderies [Sanfu huangtu 三輔黃圖] or the Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital [Xijing zaji 西京雜記].

As Zhu's own preface makes clear, such was the wealth of material on the history of the city that the proportions of his book continued to expand, so much so that he continued the labour of his son, Kuntian, following the latter's demise in 1699. This proved to be a process that did not cease with Zhu Yizun's own death in 1709. Almost one hundred years after the publication of Zhu's book, in 1774, the Qianlong Emperor (r.1736-95) ordered a supplemented version of the work produced under the nominal chief editorship of Yu Minzhong 于敏中 (1714-80). This was eventually published in 1785 under the title A Study of Accounts of the Past Heard in the Precincts of the Sun (Rixia jiuwen kao 日下舊聞考) in a massive 160 juan.

Sadly, however, as I discovered after making lengthy inquiries at the Cultural Heritage Bookshop in Liulichang, and in stark contrast to the continuing availability of the expanded version of his history of the city, despite the protection afforded Zhu Yizun's former residence by its status as a site of historical importance, the house had been demolished during one recent scheme or another for urban renewal.[8] It seems almost too obvious to say that its destruction struck me then as being powerfully metaphoric of a city that had turned its back upon its own past.

'Merely to pay Peking a fleeting visit was to be made aware of the breathtaking greatness of China's past', claims John Blofeld in his loving evocation of the years he spent living there in the 1930s, City of Lingering Splendour (1961). 'The world must be in some sort poorer for the loss of "Old" Peking', he states at the end of his book, 'The traditional Pekinese way of life was, despite the wide-spread suffering it failed to cure, a living flame from the ancient fire of a civilization as unique as it was venerable… For wisdom, urbanity, moderation, decorous behaviour, skill in arts and joyous appreciation of beauty in all its forms, [the Pekinese] remain unequalled by the inhabitants of any city in the world today' (p.255). Nowadays, it is said that a new map of Peking needs to be produced each month in the vain attempt to keep track of the changes being wrought upon large sectors of the city. A recent report in China Daily noted that 4.43m square metres of old Peking courtyard houses had been demolished since 1990, equivalent to around 40% of the downtown area. 'It is not easy to foresee how future centuries will judge the Maoist rule', argued Simon Leys in Chinese Shadows (1977), but one thing is certain: 'despite all it has done, the name of the regime will also be linked with the outrage it has inflicted on a cultural legacy of all mankind: the destruction of the city of Peking.' (p.53)

'The history of Peking is the history of China in miniature', wrote Juliet Bredon almost a hundred years ago in her Peking: A Historical and Intimate Description of its Chief Places of Interest, 'for the town, like the country, has shown the same power of taking fresh masters and absorbing them. Both have passed through dark hours of anarchy and bloodshed. Happily both possess the vitality to survive them'. No longer, it seems. 'What happens to the stories of place that have sustained lives, identities and relationships over generations?', asks Madeleine Bunting in her recent book The Plot: A Biography of an English Acre (Granta, 2009), 'Can such stories cling to the fast-changing urban environment where buildings are knocked down and rise up again in cycles outside our knowledge or control?' (p.274). All great cities, Italo Calvino reminds us, consist of 'relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past' and it makes no sense to divide cities into those which are happy and those that are not but rather 'those that through the years and the changes continue to give their form to desires, and those in which desires either erase the city or are erased by it'. As Zhu Yizun seems to have understood so long ago, such is the fate of Peking as capital that both its form and the desires that produced this form will only be available to future generations through the pages of his book.

You may also be interested in:

Notes:

[1] For a short English-language biography of Zhu Yizun, by Fang Chao-ying, see A.W. Hummel, ed., Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period (1644-1912) (hereafter, ECCP), Washington, Government Printing Office, 1943, pp.182-85. In Chinese, see Wang Limin 王利民, Boda zhi zong—Zhu Yizun zhuan 博大之宗— 朱彝尊傳, Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe, 2006. This essay seeks to engage, particularly, with two articles previously published in this journal: Bruce Doar's 'A Non-Princely Mansion from Qing-dynasty Beijing' (see China Heritage Quarterly, No.12, December 2007) and my own 'Two Private Libraries: Zhu Yizun's Pavilion for Airing Books and Qian Qianyi's Tower of Crimson Clouds' (China Heritage Quarterly, No.13, March 2008).

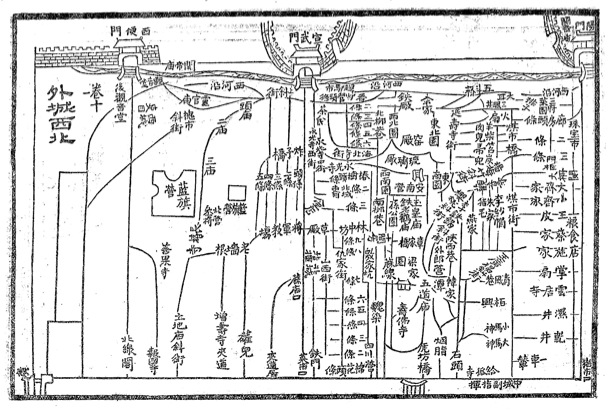

[2] Both Zhu Yizun himself ('I moved my furniture to Temple of Ocean Waves Street,/ Finding there, in the ninth month, that the green wisteria shoots had yet to wither' 我攜加劇海波寺/九月未槁清藤苗) and the map included in Wu Changyuan's 吳長元 Digest Guide to the Imperial Enclosure (Chenyuan shilüe 宸垣識略), completed in 1788 and based on the expanded version of Zhu Yizun's history of Peking commissioned by the Qianlong emperor (r.1736-95) in 1774, write the name of the street on which the Shunde County Lodge was found as 'Temple of Ocean Waves Street' (Haibosi Jie 海波寺街).

[3] For an excellent treatment of these 'Native-Place Lodges', as he labels them in English, see Richard Belsky, Localities at the Center: Native Place, Space, and Power in Late Imperial Beijing, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005.

[4] Wu Yingcai 吳英才 and Guo Juanjie 郭雋杰, eds., Ancestral Temples and House Museums of China (Zhongguode citing yu guju 中國的祠堂與故居), Tianjin: Renmin Chubanshe, 1997, pp.26-17.

[5] The residence that Zhu Yizun had been removed from stood just to the south of the Bell and Drum Towers, on which, see Wu Hung, 'Monumentality of Time: Giant Clocks, the Drum Tower, the Clock Tower', in Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Olin, eds., Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade, Chicago & Londong: The University of Chicago Press, 2003, pp.107-32.

[6] Mao # 305, entitled 'Yin wu' 殷武; this translation is that of James Legge, see his The Chinese Classics: IV: The She King Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1960, p.646.

[7] On whom, see ECCP, pp.310-12.

[8] A book on the district, Xuannan: Fayuansi 宣南: 法源寺, Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 2004, carries a photograph of a dilapidated Pavilion for Airing Books (p.36), before its demolition.