No. 24, December 2010

Ernst Boerschmann's China

Fig.1 Water-quelling beast 鎮水獸 at the Fen River 汾河, Taiyuan 太原, Shanxi province. Photograph: Ernst Boerschmann

We end the year 2010 with a focus on Ernst Boerschmann's archive of photographic images of late-imperial China. During his extensive travels in the Qing Empire on the eve of revolutionary change a century ago Boerschmann chronicled, as well as artistically captured, a world of buildings, landscapes and sights with an exacting eye, as well as with subtlety and unique grace. This issue of China Heritage Quarterly recollects his achievement in both words and in image, as well as offering a meditation on the significance of this photographer and architectural historian's work in understanding China, and its conflicted heritage, today. We are also very fortunate to be able to introduce the Research Project on Ernst Boerschmann at Berlin University of Technology under the direction of Eduard Kögel.

In T'ien Hsia we expand our own archive on New Sinology by reproducing the Inaugural Lecture of Professor Liu Ts'un-yan 柳存仁, presented at The Australian National University on 5 October 1966, and by publishing the description of a project initiated by Carolyn Cartier and Tim Oakes, 'Vast Land of Borders'. The Shanghai historian and cultural critic Xu Jilin 许纪霖 offers sombre personal reflections on China's 'examination hell' and its broader meaning, while a decade-old essay by the Editor is reproduced here as a prelude to more concerted thoughts and reflections on a century of revolution, reaction and reform in China that will feature in our issues in 2011, the anniversary year of the momentous 1911 Xinhai Revolution (Xinhai Geming 辛亥革命).

In the Articles section we update readers on the Long Bow Appeal, offer an account of the re-imagined (and heavily engineered) heritage of Qujiang 曲江 in the city of Xi'an 西安 and revisit the fate of the Forbidden City in the Cultural Revolution. Duncan Campbell recollects the monumental effort of Zhu Yizun 朱彝尊 to create an encyclopaedic account of the Qing dynastic capital during its eighteenth-century heyday, while considering a cheerless encounter with the city that has replaced it.

New Scholarship features a report on a symposium on Qing gardens and a research note on the currency of the term the 'Qianlong Garden' (Qianlong Huayuan 乾隆花園). We are also delighted to publish a series of translations related to calligraphy from the remarkable Song essayist, statesman and poet Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修.

I am grateful to Nancy Berliner of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, for guiding us to the work of Eduard Kögel in Berlin. My thanks also to Daniel Sanderson for his assistance in editing, design and layout, as well as for his suggestion that we add further readings and links at the end of our articles. Another new development in this issue is the introduction of an RSS feed to which readers can subscribe by following the link at the top of the page.

In conclusion, I would like to acknowledge the Australian Research Council which, through a Federation Fellowship awarded to me in 2005, has for the past five years supported a range of research, fieldwork and publishing ventures, including post-doctoral work, the research of PhD scholars and other academics, related to Beijing, its history and modern China. That fellowship formally came to an end in December 2010, although related research and publishing plans will continue to bear fruit over the following years. More details related to the fellowship and its results will be made available 'in due season'.

—Geremie R. Barmé, The Editor

Found & Lost:

Over One Hundred Years of Picturesque China

An Oral and Visual History Project

Sang Ye 桑曄 and Geremie R. Barmé

Fig.1 The Boddhisattva Hill 菩薩頂, Wutai Shan 五台山, Shanxi province. Photograph: Ernst Boerschmann

The photographer Ernst Boerschmann (1873-1949) first visited China in 1902 under the aegis of the German Imperial Colonial Office, the Reichs-Kolonial-Amt.[1] He travelled to the Qing Empire to explore the country, and to understand better the people, culture and architecture of China. He was based in Qingdao/Tsingtao 青島, Shandong province, the major German concession which had been ceded by the Chinese government in 1897. During that initial trip Boerschmann also visited a number of other major Chinese cities. At the time he met Joseph Dahlmann, SJ, renowned for his work on India and for his interest in the intersection between the built environment and the philosophical traditions of 'the East'.

It was a period when the newly formed German Empire (Deutsches Reich, which was created in 1871 with the crowning of the King of Prussia as its first monarch) was expanding globally; the nascent power was also anxious to prove its credentials as a major force for civilization. The German Empire's projects in China, such as support for Ernst Boerschmann, were part of a broader aim of creating an encyclopaedic cultural understanding that proved the German scientific understanding of the world and appreciation of the ancient world. Less generously, one could also describe these ventures as being part of the general European colonial scramble in Asia and elsewhere. While cultural ventures such as photographic expeditions may be seen in a relatively benign framework (and lauded in retrospect for the rich legacy that they bequeath), far less forgiving views are equally possible. These relate to the imperial strategies of the aggressively expansionist trading and colonial powers of Europe and America, activities which included the collection of geographical, topographical, social and cultural information. Such material could both pique the interest of audiences in metropolitan European centres in the exotic and different (and provide rich materials for museological and academic collections), as well as provide useful cognizance to those with well-honed political and economic ambitions.

Fig.2 Ernst Boerschmann at Fanchi County 繁峙縣, Shanxi province, en route to Wutai Shan. Photographer: unknown

Fig.3 The Great Wall at Bada Ling 八達嶺. Photograph: Ernst Boerschmann

The discussions with Dahlmann led, in March 1905, to Boerschmann drawing up an itinerary aimed at surveying Chinese architectural sites. The resulting project was supported by state secretary of the Foreign Office Oswald Freiherr von Richthofen and was awarded funding by the German government.[2] In 1906, Boerschmann began what would be a three-year project, during which time he travelled to over sixteen cities and provinces. In total he travelled twice as far as the participants in the Communist-led Long March that began nearly three decades later. While he travelled widely in China, Boerschmann was frustrated in his attempts to make work related to the imperial city (Huang Cheng 皇城) of Beijing and buildings of the Forbidden City within it: the Qing court denied him access.

His was the first systematic attempt to record the richness of China's architectural heritage, the first major display of Boerschmann's photographic work being mounted at the Königliche Kunstgewerbe-Museum in Berlin, 4 June-20 July 1912. Indeed, his field observations in China would set the standard for architectural historians for decades to come. Through the meticulous architectural drawings he made along with his photographs—an archive of great scope and variety—Boerschmann catalogued the various styles of vernacular and sacred architecture that had evolved through China's dynastic history. His body of work also directly influenced, some would claim inspired, members of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture (Yingzao Xueshe 營造學社) which was established in 1930.[3]

Boerschmann's 1931 work on Chinese pagodas ( Chinesische Pagoden) was translated by Liu Shixun 劉式訓 , a former diplomat who was also a member of the Society, and in 1932 Boerschmann himself was invited to join the Society as an executive member.[4] He made a gift of a number of books to the group but after a reorganization of the Society in 1935 he was demoted to become an ordinary member.

An important young student of architecture, and an active member of the Yingzao Xueshe, was Liang Sicheng 梁思成, later famous with his wife and partner the scholar Lin Huiyin 林徽因 as one of the great specialists on China's architectural heritage. For his part, Liang was not particularly appreciative of Boerschmann's work, nor did he have much to say of another leading figure in this field, the noted Swedish art historian Osvald Sirén. The groundbreaking work of Europeans such as these, and the stimulus it provided to academics and writers during the Republic of China, was for most of the twentieth century discounted due to the odium attached to the imperial projects of 'the West' (and indeed Japan as well—and here one thinks of the work of Sekino Tadashi 関野貞, 1868-1935).[5] It was also easy to reject their fascination with China and their work as being scholastically wanting, historically shallow and unlettered. Then, of course, there was the all-purpose condescension favoured by intellectual patriots. Wilma Fairbank reports on an appraisal of the two Europeans made by Liang in 1947:

Neither knew the grammar of Chinese architecture; they wrote uncomprehending descriptions of Chinese buildings. But of the two Siren was better. He used the Ying-tsao fa-shih, but carelessly.[6]

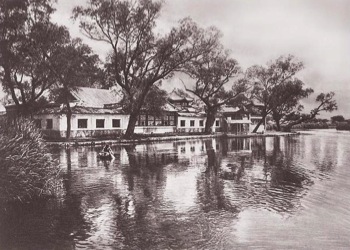

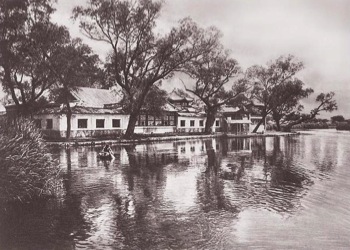

Fig.4 At Daming Lake 大明湖, Jinan 濟南, Shandong province. Photograph: Ernst Boerschmann

Given the inflamed passions of the past one can understand why the work of figures like Boerschmann was at times breezily dismissed as the product of a man who lacked any serious understanding of the profound wealth of Chinese culture and the unique heritage of its architecture. Whereas we appreciate all too keenly the controversial politics of the late-Qing/early Republican era, and the baleful legacies of colonialism as the Republic of China was struggling to realize the vision of a modern, equitable and democratic polity, we are also powerfully aware of the inspiration that China's heritage, built, natural and human, excited in academics, writers, travellers and thinking individuals. It is in this context, too, that we consider Boerschmann's work as a man who appreciated and recorded the Chinese world that he encountered, and the past that it evoked. In the process he created not only an archive of inestimable academic value, but also a body of stunning beauty. Now, a century later so many of his photographs still have the power to transport the viewer.

Today, some China-based academics and specialists find worth and value in the hard-won achievement of Boerschmann. In a greater spirit of generosity—one not as beclouded by political ire, professional pique or cultural discomfort perhaps as in the past—they appraise Boerschmann's photographic study of China, its landscapes and its building styles as being a remarkable contribution to the general wealth of knowledge. For Boerschmann's work predated by many years that of later specialists—such as, architectural historians, photographers and official government recorders. Today he is gradually being recognized for his breadth of vision, the richness of the material he collected and the serious intellectual underpinnings of his enterprise (see the Editorial in this issue for more on this).

Although Boerschmann published a number of works about China (see the Selected Bibliography at the end of this essay), we have chosen to use Picturesque China: a journey through twelve provinces (Baukunst und Landschaft in China: eine Reise dürch zwölf Provinzen), which originally appeared a century ago, as the basis for a project initiated in 2006 by the oral historian and traveller Sang Ye aimed at revisiting the sites of Boerschmann's work and recording, both visually and through short oral histories, their fate during a hundred years of momentous change. In pursuing this work we believe that Picturesque China reflects well the range of Boerschmann's visual interests as well as the breadth of his geographical engagement with that country. It was also a work created at a particular moment in the late-Qing era, a moment which we believe resonates in complex ways with views of heritage, history and the past in the present.

Fig.5 Leifeng Pagoda 雷峰塔 and West Lake 西湖, Hangzhou 杭州, Zhejiang province. Photograph: Ernst Boerschmann

Fig.6 Outside the Yue Fei Temple 岳廟外, West Lake, Hangzhou. Photograph: Ernst Boerschmann

In the preface to Picturesque China Boerschmann wrote:

The present is flux, the future veiled, but the past is immutable and clear. It is only from the past that we learn to comprehend our own checkered lives. We can hardly interpret them without its aid…. The monotony of our workaday lives, and the tempestuous present sometime hold us with terrible force. We are rendered breathless, and then we almost despair of humanity. China too is now in a state of nearly complete confusion. That which exists passes, and immense works of culture perish. At the same time new ones are being created everywhere. The real spirit of people is imperishable even in a new epoch. We help to disclose this nucleus if we hark back to the ultimate meaning of architectural monuments…

Sang Ye and his collaborators in Australia, China, Taiwan and Canada, include historians, photographers and a specialist in satellite mapping. They are utilizing the selected, publicly available archive of Boerschmann's photographs as collected in Picturesque China to trace a particular history of place. Sang Ye, Jin Xiong 金雄 and Lao Cheng 老成 have been working to identify relevant sites. Photographic work is being undertaken by: Jin Xiong, Xu Yuan 徐原, Ge Xiaoxia 葛小夏, Yu Peng 宇鹏 and Zhang Baotian 張寶田, while background research and the writing up oral history material is being done by Sang Ye with Geremie R. Barmé. Legal advice has been provided by Shi Baojia 史寶嘉.

Of the 288 photographs in Picturesque China over 200 were made by Boerschmann himself, another forty or so being the product of Chinese photographers in his employ. Sang Ye and his collaborators have identified the sites of the original photographic works, travelled to them and made photographs from as near to the same vantage point as Boerschmann as possible. Of them forty-two are now protected in China as national cultural heritage sites (guojiaji wenwu baohu danwei 國家級文物保護單位), some have even achieved UNESCO World Heritage status. Another eighty are provincial or municipal-level cultural heritage sites (shengshiji wenwu baohu danwei 省市級文物保護單位). Such status does not necessarily ensure the integrity, or even security, of a particular site. For instance, over twenty buildings such as the Confucius Temple in Qufu 曲阜孔廟, the Grave of Yue Fei in Hangzhou 杭州岳墳, the Jinci Temple in Taiyuan 太原晉祠, as well as the Taishan Temple at Taishan 泰山岱廟 have been substantially or completely reconstructed. Another sixty sites/buildings have disappeared entirely.

Fig.7 Steps leading to Shoushu Lou on Mt Zibo 紫柏山授書樓, part of the Zhang Liang Temple (see the account of the Temple of Duke Liu below), Liuba County 留壩縣, Shaanxi province. Photograph: Ernst Boerschmann

The reasons for such despoliation are varied. In order of magnitude the devastation ranges from that wrought by the Cultural Revolution, national reconstruction, the Japanese War, the Civil War, the Great Leap Forward, to the three decades of economic boom, as well as the collapse of the Qing empire. The project, which will result in published work as well as a web-based archive, will provide a full list of these, but it includes:

During the Japanese War: The destruction of five temples and structures in Changsha, Hunan province, including the Zuo Wenxiang Temple 左文襄祠;

The Three Gorges Dam: ten sites destroyed, four moved and rebuilt and another six submerged;

The mixed fate of sites such as the Wenchang Palace (Wenchang Gong 文昌宫) in Fengling 灃陵, Hunan province: one building was blown up during the Japanese War; two were torn down during the Great Leap Forward. The only remaining structure, the Hall of the Ancestor of Agriculture (Xiannong Dian 先農殿) was spared because Mao Zedong had stayed there in the 1920s when carrying out his survey of the Hunan peasant movement;

Natural disasters (such as earthquakes and floods): only 2% of the sites recorded by Boerschmann were lost in this manner.

Over the years that this project has been undertaken, Sang Ye has been conducting short oral history interviews with local people—residents, historians, workers, farmers, bureaucrats—which elucidate the stories of these sites. Some trace the century since Boerschmann made his work through a simple narrative; others reflect one aspect of a more complex history.

Many of the sites changed beyond recognition; none have remained untouched by the passage of time, and the impact of events. Below we give a number of examples of the images that will be juxtaposed in the final publication and website, and some of the oral history material undertaken by Sang Ye. 'Found and Lost' is a story of the concrete and of the ephemeral; of the inexorable workings of time and of the vicissitudes of humankind. As Boerschmann himself observed: 'It is only from the past that we learn to comprehend our own checkered lives.'

The authors would like to thank Claire Roberts for her comments and suggestions.

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly:

Selected Bibliography of Works by Ernst Boerschmann

This short bibliography is based materials at the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, including resources primarily from the Herbert Offen Research Collection. See also the Catalogue of the German National Library (Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek).

Ernst Boerschmann, Chinesische Architektur, Berlin: E. Wasmuth, 1926.

Ernst Boerschmann, Chinese architecture and its relation to Chinese culture, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912.

Ernst Boerschmann, Chinesische Baukeramik, Berlin: A. Lüdtke, 1927.

Ernst Boerschmann, Die Baukunst und religiöse Kultur der Chinesen, Berlin: G. Reimer, 1911-1931.

Ernst Boerschmann, Old China: in historic photographs: 288 views, New York: Dover; London: Constable, 1982.

Ernst Boerschmann, Picturesque China: architecture and landscape; a journey through twelve provinces, London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1926.

恩斯特·柏石曼, Xun fang 1906-1909: Xiren yanzhongde wan-Qing jianzhu (1906-1909: 西人眼中的晚清建筑), trans. by Shen Hong, Tianjin: Baihua Wenyi Chubanshe, 2005.

Notes:

[1] For a biographical note on Boerschmann, see Fritz Jäger, 'Ernst Boerschmann (1873-1949)', in Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 99 (N.F. 24), 1945-1949 (1950): 150-156.

[2] Oswald von Richthofen was was related to both the 'Red Baron', Manfred von Richthofen, a flying ace during WWI, and Ferdinand von Richthofen, a leading academic and geographer and President of the German Geographical Association. For some time the Qilian Mountains in Gansu were known among non-Chinese as the Richthofen Range.

[3] For a mention of this Association and Zhu Qiqian 朱啓鈐 (1872-1964) in the pages of this journal, see 'Zhu Qiqian's Silver Shovel', China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 14 (June 2008), at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=014_zhuQiqian.inc&issue=014. See also Cui Yong, Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe yanjiu, Nanjing: Dongnan Daxue Chubanshe, 2004; and, Lin Zhu, Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe shilüe, Tianjin: Baihua Wenyi Chubanshe, 2008.

[4] For these details, see Journal of the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture (Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe Huikan), No.3, Vol.2 (1931) and No.1, Vol.3 (1932).

[5] See, for example, Daijo Tokiwa and Tadashi Sekino, Buddhist Monuments in China, Tokyo: Bukkyoo-shiseki Kenkyuukai, 1926.

[6] Quoted in Wilma Fairbank, Liang and Lin: Partners in Exploring China's Architectural Past, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994, p.29.

Online Resources:

For an online collection of Boerschmann's work divided by province, see: http://www.pbase.com/lambsfeathers/boerschmann

For a useful online bibliography, see Thomas H. Hanh's 'Bibliography of Photo-albums and Materials related to Photography in China and Tibet before 1949' (1949 nian qian Zhongguo sheyingshi wenxian ziliaoku 1949 年前中国摄影史文献资料库), at: http://maximumcities.net/Photoweb/entries.html#b

For a recent documentary film featuring Liang Sicheng, see 'Liang Sicheng Lin Huiyin' 梁思成林徽因, directed by Hu Jingcao 胡劲草. For the official website of the film, go to: http://jishi.cntv.cn/program/lianglin/lianglinft/index.shtml For YouTube links to excerpts, see: http://bbs.wenxuecity.com/tv/467324.html See also 'Hu Jingcao on Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin', an interview with the film's director by Benjamin L. Read, a professor of politics at UC Santa Cruz, published by China Beat on 6 December 2010, at: http://www.thechinabeat.org/?p=2958