|

FEATURES

Perceptions of Change, Changes in Perception | China Heritage Quarterly

Perceptions of Change, Changes in Perception

West Lake as Contested Site/Sight in the Wake of the 1911 Revolution

Eugene Y. Wang 汪悅進

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Professor of Asian Art

Harvard University

Eugene Wang's study combines two themes pursued by China Heritage Quarterly in the second half of 2011: West Lake and the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. Wang's considerations of the Lake in the early, revolutionary years of the Republic of China resonate with the discussion of the same period by Liping Wang (also in Features in this issue), as well as Liping Wang's work on the Qing emperor Kangxi and West Lake. His journey through early modern representations of the Lake engages with Erwo Xuan, which Claire Roberts speaks about in her work on Chinese photography. Here too we are allowed a different, visual perspective on the Temple of Yue Fei, which overlaps with Zhou Zuoren's essay on the martyr-general and Qin Gui, translated by Tim Cronin (also in Features). And throughout we return, time and again, to the Ten Scenes, each era adding to the palimpsest of representation and memory that overlays the physical reality of West Lake.

This work originally appeared in the pages of Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Vol.12, No.2 (Fall 2000), in an issue devoted to Visual Culture and Memory in Modern China edited by Julia F. Andrews and Xiaomei Chen. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author with minor stylistic changes, although the citation style and bibliography of the original print version have been retained. It is presented here in two parts:

Click here to download a PDF of the original article. For more downloadable PDF-format research papers by Professor Wang, click here.— The Editor

Changing Views of Monuments

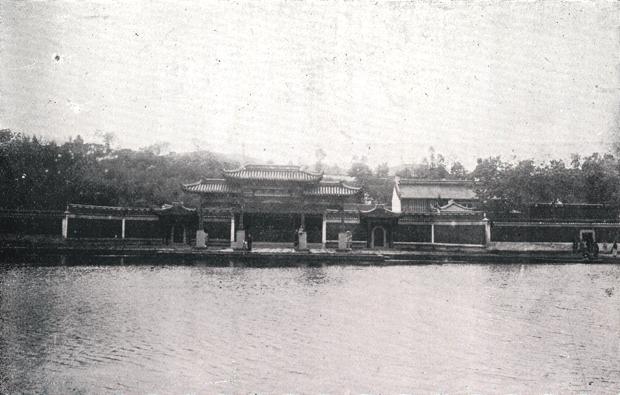

Fig.14 View of Shengyin Temple. 18th century. From XZ: 3.4-5.

�

Monuments along the lakeshore fulfilled that role. 'Looking around at the lakeshore,' Huang notes in his Preface, 'one sees the Public Park, Library, the Memorial Hall for Soldiers Who Died in Nanjing, the Shrines for Martyr Tao, Tombs of the Three Martyrs (Xu, Chen, Ma) and the Shrine for Lady Qiu of Jianhu.' The monuments listed here were spread along the shore of Solitary Hill (Gushan 孤山) and extended to the southwest shore.[Figs 2&3] Particularly significant is the site occupied by the Public Park and the Memorial Hall for Soldiers on the south side of Solitary Hill. As shown in an eighteenth-century print, the compound encompassing the park and the memorial hall used to be the Temple of His Majesty's Visitation (Shengyinsi 聖因寺), the imperial itinerary palace for Qing emperors during their Southern Inspection tours [Fig.14]. The photograph in the 1910 album shows the wharf surmounted by an imposing gateway that proclaims the pre-eminence of the place. The shot of the front of the square adds to the solemnity of the site. The choice of the wharf evokes the arrival of the imperial entourage across the lake,[Fig.15] a conceit often used in marking the itinerary of the Qing emperors' Southern Inspection Tours.[14]

Fig.15 Public Park [Wharf Leading to the Shengyin Temple]. Before 1910. From XHFJ: 20.

�

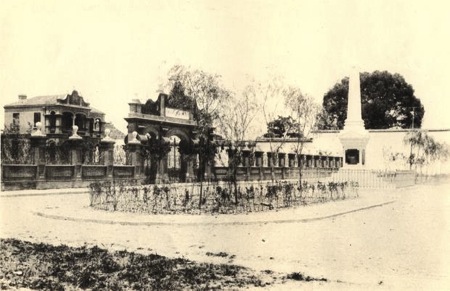

Huang took two photographs of the site. One reframes the vista from the side so that the wharf gateway becomes slender and foreshortened, dwarfed by the soaring obelisk on the right.[Fig.16] The Chinese caption on the photograph reads:

The Memorial Hall of the Patriots was built on the foundation of the Temple of His Majesty's Visitation. On its side is the Public Park. Bordering the lake is the huge gateway. Away from the wharf is the obelisk.[15]

Huang never seems to get enough out of the memorial obelisk. In another photograph, he shoots the obelisk-dominated site from another angle, this time to include the brick archway and the Memorial Hall of the Patriots. The entire vista is thus filled with the Western-style architectural design.[Fig.17] The three-arch entrance seems to be a triumphant statement that mocks and plays down the traditional Chinese-style wharf gateway.[Fig.15] Huang praises 'these imposing new edifices' for their 'infinitely

varied sublime aura' (qixiang wanqian 氣象萬千).

Fig.16 Huang Yanpei. The Memorial Hall of the Patriots (Soldiers Died in the First

Revolution, 1910) and the View in Front of the Public Library Garden. 1914. From ZMX: 3:9.

Fig.17 Huang Yanpei. The Monument in Front of the Memorial Half of the Patriots. 1914. From ZMX: 3:10.

What merits our attention is the key term 'sublime aura' (qixiang 氣象), a term also used by Huang's contemporaries in formulating their visual impressions of the same monuments. Gao Xie, also a revolutionary, notes in his travelogue that the Memorial Hall for Soldiers, the Public Park, and the Zhejiang Library 'were built on the foundation of the itinerary palace of the Temple of His Majesty's Visitation. Their grand scale creates a completely new sublime aura' (qixiang yixin 氣象一新). Just as Huang was fixated on the obelisk, Gao also singled it out: 'the stone pillar' struck him as 'soaring and dignified' (wei'e 巍峨) (XYH: 23: 2).

It is highly significant that Huang and Gao used the same phrase. The landscape of West Lake had traditionally been praised for its effeminate delicacy,[16] or felt to be an anemic and frail beauty,[17] lacking in 'sublime aura'.[18] With the addition of Western-style memorials, however, the landscape took on a 'sublime aura'. As a descriptive category, the term 'sublime aura' has an enduring currency in traditional literary criticism. It was used extensively in the Southern Song period, in treatises by Jiang Kui, Yan Yu, and others, who correlated the term with the poetic mood of bucolic serenity captured in Tao Qian's 陶潛 (365-427) lines: 'I picked a chrysanthemum by the eastern hedge, / off in the distance gazed on southern mountain.'[19] The modern sense of the term departs substantially from its earlier denotation of a bucolic tranquility. By the early twentieth century, the term had acquired new meanings: it came to be associated with the poignant sight of ancient ruins and memorials with overtones of a somewhat forbidding austerity and stirring magnitude.[20] There is no mood of ruin to speak of here, for the new memorials, which Huang photographed and Gao saw, were either new or newly refurbished. What is significant is that Gao's response signals the shift from the earlier bucolic vista to architectural monuments as the structural cue for 'sublime aura'.

The old mode of perception, however, died hard. Chen Yilan, the Shanghai woman, also came to this site on her tour. The things that claimed her visual attention were different from those of Huang and Gao. While her uncle got engrossed in books in the library, she and her siblings sat underneath the wharf gateway to watch the lake made hazy by a sudden downpour. She regretted that she did not have the skill to paint a 'Picture of Encountering Rain on the Lake' (Hushang yuyu tu 湖上遇雨圖), which tells us that she had a clear notion of what makes the picturesque. She toured the Public Park, mindful all the while that it used to be the site of the Temple of His Majesty's Visitation and regretting her failure to see some of the artifacts once used by the emperors. To her, the best views were the panoramic views obtained by climbing up to a high vantage point in the park. These vistas of spatial immensity struck her as having a 'sublime aura' (qixiang kongkuo 氣象空闊) (XYH: 24: 8). Chen used the term 'sublime aura' to formulate her visual impression; yet she used it differently from her revolutionary contemporaries who were so inspired by the new architectural grandeur. She entertained a notion of what makes a 'sublime aura' that was still largely in keeping with the more traditional sense of the term. She did acknowledge the 'soaring marble memorial' (i.e., the obelisk), but did not bother to point out its political reference. Western-style architectural designs did not seem to impress her much. 'Those little pavilions,' she moaned, 'are mostly recent additions. They draw on the western style. They cannot be compared with the old-style design, and are likely to be reduced to ruins in a few years' (XYH: 24: 8). It is therefore not surprising that the new memorial obelisk and hall did not solicit from her the kind of praise offered by Huang and Gao. Chen was precisely the kind of viewer for whom Huang Yanpei's 1910 photographs of the site were taken, However, Huang's many photographs of the memorials for dead revolutionary soldiers would not have attracted her attention. Nor would they have struck a sympathetic chord in Fang, the high schooler, who deliberately skipped the site, presumably for lack of interest. It would have been disconcerting to Huang and his revolutionary peers that the memorial for revolutionary soldiers, designed to perpetuate memory of the revolutionary martyrdom to posterity, failed to speak to young men and women like Fang and Chen, who were their immediate heirs.

Whereas the Shanghai woman saw a 'sublime aura' in the view of West Lake shrouded in rain, the same scene struck Huang the photographer differently. It was on a rainy day that he returned to West Lake two decades later. Looking out from the Four-View Pavilion (Sizhao ge 四照閣), Huang was greeted by the sight of 'the lake and surrounding hills turning into one color only, the gray. …The gray clouds and mist appear to be struggling hard, making one feel like neither crying nor smiling.' This scene in the hands of literati painters, Huang notes, would have occasioned a painting called 'Conversing at a Lakeside Pavilion in Rain' (Hulou huayu 湖樓話雨). However, it left Huang cold. The mellow rainy scene prompted him and his friends to engage in a heated debate about the traditional Confucian value of 'equilibrium and harmony' (zhonghe 中和), to which they attributed the failure in China to produce 'great heroes like Alexander, Caesar, or Napoleon, in the West, and Genghis Khan in the East.' The historical reflection culminated in Huang's poetic rumination:

A thousand layers of melancholy crush the wine cups.

If inadequate is the photographic depiction,

Where can one acquire the divine power to invoke wind and thunder? (1934: 7-17)

Tombs and Topoi

Fig.18 Huang Yanpei. Tomb of Miss Su Hsiao [Su Xiaoxiao]. 1914. From ZMX: 1:20

Huang's photographs include some very unphotogenic scenes, in particular, tombs.[Fig.18] Insofar as the picturesque is concerned, these unsightly mounds do not make much of a 'view.' However, in a culture that prizes markers of physical traces—real or fictive—of antiquity, tombs are often arresting sites of intense visual attention and emotional loitering. Marking 'traces' (ji) of past individuals and lores, these tombs and graves infuse the present landscape with a storied past, thereby transporting visitors not only to 'nature ' but also back to past worlds. They figure prominently in the landscape of West Lake. Gazetteers of West Lake; vary in their classifying systems, but they invariably include a section on 'Graves and Tombs'.[21] It is customary for traditional literati to visit West Lake in search of the tombs of legendary figures. Tombs were scattered all over the lake area, but the strip at the foot of North Hill near the West Coolness Bridge (Xiling qiao 西泠橋), which links the north shore to the west end of Solitary Hill,[Fig.3] has a particularly high concentration of tombs. To this area were added new tombs of martyrs who had died around the 1911 Revolution. Old tombs, particularly of historical personages with contemporary resonances, such as that of Yue Fei 岳飛 (1103-1141), the twelfth-century anti-Jurchen general, were renovated. The area attracted renewed attention after the 1911 Revolution.

Prominent in the area is the tomb of Su Xiaoxiao 蘇小小, as seen in Huang's photograph.[Fig.18] A combination of factors drew visitors to her tomb. According to legend, Su, a fifth-century courtesan, meets a young man on the lakeshore: she in her curtained chariot, he on horseback. She expresses her feelings for him in a poem. They fall in love and are married, but the man's conservative parents break up the marriage. Su suffers neglect and dies of a broken heart. A former beneficiary of hers is said to have buried her body close to West Coolness Bridge, presumably to honor her poetic vow that she and her lover should wed under the 'pines and cypresses of West Hill.'[22]

Many have puzzled over Su's lasting celebrity and appeal. Shen Fu 沈復 (1763-1807?), for instance, asks why the fame of 'one mere courtesan' has endured for so long, whereas many illustrious martyrs and virtuous paragons have since lapsed into obscurity. It is, says Shen, mainly Su Xiaoxiao's 'inspired and animated spirit' (lingqi 靈氣), which 'embellishes the landscape', that explains her lasting appeal (1993: 75). In other words, tombs endure in a landscape if their occupants accommodate people's perception and expectations of the landscape. Frequently shrouded in mist and clouds, West Lake has been perceived as a feminine landscape, and the tomb of Su Xiaoxiao embodies these feminine qualities. Part of the appeal of the tomb was that its whereabouts were uncertain, at least until the eighteenth century. For tourists with literary dispositions, to search for the tomb and to end up in a delicious uncertainty were an integral part of the emotional experience of touring West Lake. The elusive tomb easily conjures up fantasies of a spectral beauty haunting the lakeshore. Her legendary encounter with the young man suggests a perpetual possibility of re-enactment for romantically inclined male visitors. Every now and then there were reports of visitors' delirious, often fatal, encounters with the spectral beauty (XXZ: 9: 5). The tomb lived in 'fiction and unreality', and its all ure resided precisely in a misty ' illusory horizon,' with its presence registered in the form of the faint 'scent of chrysanthemum' (XXZ: 9: 5). In 1780, Emperor Qianlong's inquiry into its whereabouts led to the construction of a stone tomb, with a stele on it announcing 'Tomb of Su Xiaoxiao of Qiantang' (Lu 198 1: 75-78). 'From that moment on,' Shen Fu sighs, 'it was no longer possible for romantic poets with antiquarian obsessions to search and loiter around the area' (Shen 1993: 75). Evoking female beauty and hazy cloudiness, the Su Xiaoxiao tomb, whose aura had been created by word of mouth until the eighteenth-century construction of the tomb ended it, is a figuration of the West Lake landscape. The predominant mood it creates is therefore, as Shen Fu puts it, an 'inspired and animated spirit'.

In his photographs of the site, Huang seems to treat the subject in this traditional manner. The site, however, did not seem to elicit much interest from our tourists, with the exception of Gu Wujiu, who came to the West Coolness Bridge with a few other Southern Society members to 'pay homage to Tomb of Su Xiaoxiao'. One of them inscribed a poem on the pavilion near the tomb, which included the couplet:

With Xiaoqing's 小青 death, a close companion is no more,

Who will then pour wine on [your] tomb?

The poem struck Gu as 'hauntingly touching' (chanmian feice 纏綿悱惻), provoking in him 'endless sighs and thoughts' (Cao 1985: 108). One would imagine that Chen Yilan, the Shanghai woman, with her refined feminine sensitivity, would have responded more sympathetically to this site so heavily laden with the sad fate of a frail beauty. Surprisingly, she was untouched by the site. 'It is a senseless pile of rubble,' she observed, largely unimpressed. 'For the so-called Golden Powder of the Six Dynasties, where is her scented chariot? A one-time talent comes down to a dark tomb. That is it' (XYH: 24: 16). Gao and Fang, for their part, largely passed over the tomb in their travelogues.

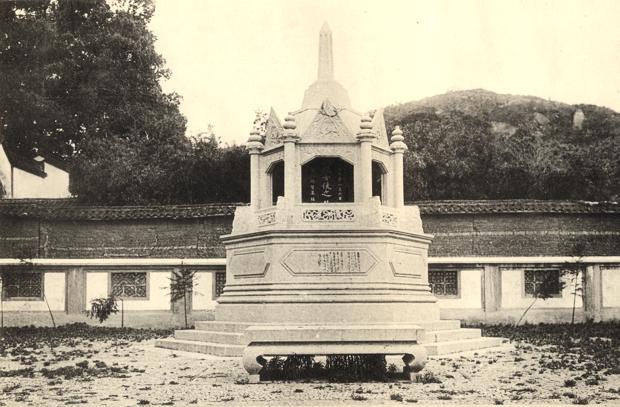

Fig.19 Huang Yanpei. The Tomb of Ch'iu Chin [Qiu Jin] (A Martyred Woman Revolutionist). 1914. From ZMX: 3:12.

�

A conspicuous modern rival to the Su Xiaoxiao tomb stood nearby. To the west of West Coolness Bridge, on the north shore of the lake, was the tomb of Qiu Jin 秋瑾 (1875-1907).[Fig.19] A native of Shaoxing who had studied in Japan, Qiu Jin was one of the leaders of the Zhejiang revolutionary movement. When her plans we re discovered by the Qing authorities, she chose to put up a token resistance rather than escape. After she was arrested, she remained un repentant and openly stood up to her captors' intimidation.[23] She was beheaded at the age of thirty-one. Her body was buried by some charity establishment. The following year, her friends, Xu Zihua 徐自華, Wu Zhiying 吳芝瑛 and Chen Qubing 陳去病 (the editor of Chinese Woman's Newspaper), transferred he r body to a place next to the West Coolness Bridge and entombed it there to honor her wish that 'should I die unfortunately, I would like to be buried close to the West Coolness [Bridge].' Fearful of its incendiary implications, the Qing authorities announced their intention to destroy the tomb. So Qiu's relatives took her body back to Shaoxing and then to Hunan, her husband's native place. After the 1911 Revolution, at the request of her friend Wu Zihua, Qiu's body was returned to the tomb at the foot of North Hill. A shrine at the tomb site was built in her memory. Included in the memorial compound was the Pavilion of Wind and Rain (Fengyu Ting 風雨亭), a name that alludes to Qiu's parting words, a poetic line she had composed before her execution: 'The sorrow of autumn wind and autumn rain kills' (qiufeng qiuyu chou sha ren 秋風秋雨愁煞人). The poignant line quickly became a staple of the Qiu Jin lore.[24]

Fig.20 The Qiu Shrine [Pavilion of Winds and Rains]. From XHFJ; 34.

A photograph shows the pavilion to be a wooden-pillar-supported structure on a hexagonal stone foundation, largely a Chinese design with some European stylistic flavor.[Fig.20] In contrast, Qiu's tomb was made of stone in a predominantly Western style, as shown in Huang Yanpei' s photograph.[Fig.19] The two structures thus form a sharp contrast in design and solicit divergent perceptual responses: the slender wooden pavilion has a feminine feel, whereas the stout and sturdy stone tomb has a robust air. The pavilion evokes the dolefulness and pathos of the woman poet's tragic death, the tomb the unyielding and austere heroism of her sacrifice for the revolution. The two structures inadvertently embody two aspects of Qiu Jin's persona, hence two ways of representing and perceiving the woman martyr. In his photographs, Huang Yanpei opted for the tomb. The ideal he projects through his photographic representation of Qiu Jin is therefore a robust one, not the plaintive pathos of 'autumn wind and rain.'

Huang's photographic message would not have been lost on Gao Xie, a fellow revolutionary. In his travelogue, Gao recounts the history of the tortuous process by which Qiu's body was finally returned to West Lake and entombed near the West Coolness Bridge. On an earlier trip, presumably after the Qing authorities had the tomb removed from the site, Gao had lamented that 'the new tomb at the West Coolness is no longer to be found.' Now he was gratified to see it restored. However, as a leading member of the Southern Society, his response to the site is curious. The early Southern Society members, including Gao Xie himself,[25] were deeply involved in mourning Qiu Jin's death. Poetic evocation of the 'autumn wind and autumn rain' was common among them.[26] The pavilion named on the basis of this poetic line became a mourning site, drawing a flux of visitors, including Dr. Sun Yat-sen, who in 1912 paid tribute and composed a poem in Qiu's memory. Yet, Gao Xie seems to take little notice of the Pavilion of Wind and Rain that so explicitly evokes Qiu's tragic death. As if in complicity with Huang's perceptual choice, he fixed his attention on the sturdy tomb and noted the inscription on it by Mr. Zhu, the new governor of Zhejiang: 'these big characters are deeply engraved, each like a fist. [The tomb] is a lofty structure indeed.' His preoccupation with the martial spirit was such that he had nothing to say about the pavilion and averted his eyes to focus on another nearby tomb. He noted:

Beside the Pavilion of Wind and Rain is an earthen mound, reputed to be the Tomb of Wu Song 武松. It is not found in gazetteers or history books. Nor do we have stelae as basis for investigation. I thereby composed a poem to honor it. (XYH: 23: 2)

The name Wu Song conjures up in many visitors' minds the tiger-killing hero from the novel The Water Margin, though the tomb here is purely a make-believe construct without any historical basis.[27] It strikes us as a bit odd that Gao, a Southern Society member and an erudite scholar, would have composed a poem for a fictive martial character instead of for the real-life martyr with whom he had a close political affinity. It perhaps reveals Gao's immersion in the martial spirit that permeated the tombs of both Qiu Jin and Wu Song, and not the pavilion. The martial effect of Qiu's tomb was not even lost on Fang, the high school boy from Shanghai. He looked closely at Qiu's portrait enshrined at the site and saw a ' heroic martial air' (yingxia zhiqi 英俠之氣) in her physiognomy. He lamented that someone like him, who could not make a name for himself in the world, is condemned to shame in front of this heroine (XYH: 25: 5).

Fig.21 Su Manshu. Yue Fei Visiting the Hill Pavilion. Ink and color on paper. Before 1918. Collection unknown. From PHRC: p. 66.

Reinforcing this martial spirit is the tomb of Yue Fei some distance west of the Qiu Jin tomb. In the late-Qing and early Republican periods, the historical matter of Yue Fei, the twelfth-century Chinese military commander who spectacularly routed the Jurchen invaders and then died at the hands of pacifist ministers, became a poignant and stirring theme frequently featured in anti-Qing rhetoric. Yue Fei's martyrdom was also frequently invoked in the context of Qiu Jin's death. The two became interchangeable tropes serving one anti-Qing rhetorical end. This conceptual connection between the two was facilitated by the proximity of their tombs at the foot of North Hill west of West Coolness Bridge.

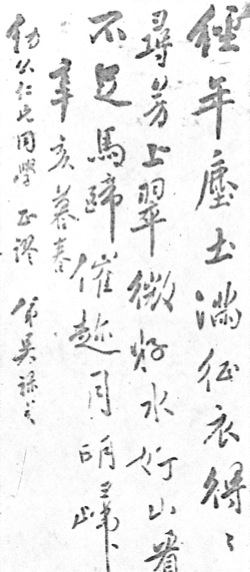

Like the Qiu Jin lore, the Yue Fei subject also involves two modes of representation, neatly epitomized by the opposition between a pavilion and a tomb. The pavilion in question is known as the Hill Pavilion (Cuiwei Ting 翠微亭), located in present-day Guichi 貴池 County, Anhui Province, and allegedly built by the eighth-century poet Du Fu. The pavilion acquired an additional layer of fame through Yue Fei' s well-known poem 'Ascending the Hill Pavilion at Chizhou 池州':

My expedition uniform full of dust gathered over the years,

My galloping horse clip-clopping , I came upon the Hill [Pavilion], seeking the fragrance.

Never can I have enough of the view of the beautiful landscape out there,

Yet I have to return, my horse's hoofs chasing the moonlight.

The poem became practically a battle song for the Republican fighters in the early twentieth century. A painting by Su Manshu 蘇曼殊 (1884-1918), a brilliant scholar and member of the Southern Society, visualizes Yue's poetic scenario. Bathed in moonlight, the Hill Pavilion is perched high to the right. Yue Fei on horseback lingers at the foothill, struggling to tear himself away from the landscape and return to the battlefield. On the upper portion of the painting is inscribed a complete transcription of Yue Fei's poem by Zhang Taiyan 章太炎 (1869-1936), a radical revolutionary thinker.[Fig.21] It is no coincidence that Wu Luzhen 吳祿貞 (1879-1911), a military officer of the northern New Army and a leading revolutionary, transcribed the same poem in calligraphy in the late spring of 1911,[28] a few months before he was assassinated.[Fig.24]

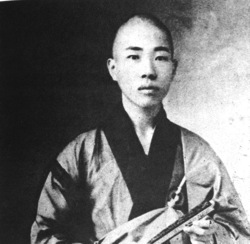

Fig.22 Photograph of Su Manshu

Fig.23 Photograph of Wu Luzhen, ca. 1911

The two examples demonstrate the popularity of Yue Fei's poem among Republican fighters and agitators. More significantly for our purposes, the pavilion comes to be central to a new iconography of landscape. A pavilion in moonlight is a familiar poetic setting and pictorial motif, usually visited by a wine–toting immortal or a poetry-composing literatus. With the insertion of a military commander on horseback, the scene is invigorated with a potency not found in more conventional uses of the motif. The mellow serenity of the landscape belies the turbulence and agitation beyond the picture frame.

This new landscape iconography had surprisingly wide currency around 1911. A photograph taken during the 1911 Revolution shows members of the Jiangxi Revolutionary Alliance assembled in front of a pavilion. A saddled horse is placed as a prop facing the pavilion, thereby evoking and enacting the poetic scenario of Yue Fei's visit to the Hill Pavilion.[Fig.25] The original pavilion that inspired Yue Fei' s poem is in Anhui. Another, inspired by Yue's poem, was built at West Lake in 1142, one year after Yue Fei's death, by Han Shizhong 韓世忠 (1084-1151), a Southern Song military commander who, like Yue Fei, ran afoul of Qin Hui. To commemorate Yue Fei, Han built a pavilion halfway up the Feilai Hill 飛來峰 (Wang 1934: 910a) , However, in spite of the fame of the pavilion as a poetic setting in the period of the 1911 Revolution, the pavilion on Feilai Hill did not attract the attention of many tourists. Huang did not choose it as a photographic subject, nor did our tourists make special note of it. They were instead drawn to the tomb of Yue Fei at the foot of North Hill.

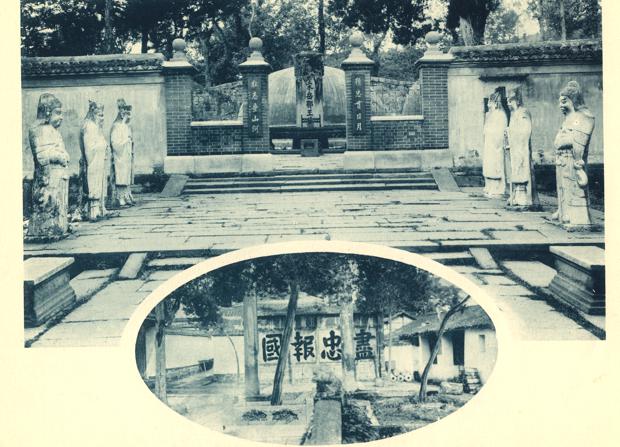

A comparison between a late Qing photograph [Fig.26] and the one taken by Huang Yanpei [Fig.27] shows the indelible marks of the post-revolution renovation. The traditional three-bay plastered gateway is replaced with a Western-style brick structure. Huang's photograph was shot rather close to the tomb, which stresses its magnitude 'and makes it possible for the viewer to read the calligraphic couplet flanking the entrance:

Undivided loyalty reaches the sun and moon,

Heroic aspirations extend to mountains and rivers.

As if this were not enough, Huang also adds an oval photograph insert that shows the yard outside the tomb and the four gigantic calligraphic characters on the facing wall: 'Pledge loyalty to the country' (jinzhong baoguo 盡忠報國). Huang's caption for these two photographs reads: 'The tree branches in front of the tom b all face south. Beyond the gate are the statues of Qin Hui 秦檜, his wife Lady Wang, Moqi Xie 万俟卨, and Zhang Jun 張俊. They are shown hand-cuffed at the back, kneeling below the Dew Terrace.' The statues were made in the sixteenth century (Ye/Lü 1982: 73) and have since become effigies of the villainous ministers who persecuted Yue Fei, urinated upon by many a visitor. It is interesting that Huang chooses not to include these kneeling statues in his photographs, even though he hastens to mention their presence in the caption. Presumably, he considers the statues too repulsive to be treated as 'views', even though the melodramatic rhetoric called for by the site was not lost on him.

Fig.24 Wu Luzhen's calligraphic transcription of Yue Fei's Visiting the Hill Pavilion. Dated 1911 . From PHRC: p.138.

Our four visitors all came to Yue Fei's tomb. Chen Yilan tarried at the tomb, noting carefully the poetic couplets around it. Her moral sentiment was stirred, she tells us (XYH: 24: 7). Fang, the high school boy, lingered at the tomb 'endlessly,' 'paying homage and sobbing.' Although such feelings were no doubt genuine, there is also an indication of some set literary prototypes directing and formulating them. Gu Wujiu and Gao Xie, for instance , both visited the site, though with separate groups. They describe their impression in nearly identical terms. Gu Wujiu recalls 'solemnly paying tribute to the tomb, which inspired awe in me and led me to visualize Yue's person' (surong zhanbai, linran xiangjian qi weiren 肅容瞻拜,凜然想見其為人) (Cao 1985: 108). Likewise, Gao Xie says that he 'solemnly paid tribute to the tomb, which inspired such a noble sentiment in me that I visualized Yue's person' (surong zhanbai, kairan xiangjian qi weiren 肅容瞻拜,慨然想見其為人) (XYH: 23: 4).

Although Huang may highlight the tombs of modern revolutionary martyrs through his photographic focus, the public—including some revolutionary activists themselves—did not necessarily favor them over more traditional monuments. It is striking that all four visitors seem to have been affected more by the Yue Fei tomb than by the Qiu Jin tomb, even though the latter was closer to them in time and her death no less dramatic and emotionally stirring than that of Yue Fei. Gu Wujiu thought Qiu's tomb contributed substantially to the landscape. Gao Xie, the other Southern Society member, recounted the tortuous process through which Qiu's tomb was finally moved to the current site, perhaps to remind his contemporaries of the danger of Qiu Jin lapsing into obscurity. His account was surprisingly flat in its emotional register. The Shanghai woman felt that Qiu's death was 'extremely unjustifiable,' yet she had nothing else to note except that Qiu wore a kimono in her portrait and that the stone masonry of her tomb must have cost 'one or two thousand [tael] of cash.' In other words, some perceptual and cultural habits die hard: landscape is charged with historical memories and visitors to West Lake search for 'traces of the past' (guji). The inherent interest of a site is derived from the tension the site evokes between the distant past and its palpable physical presence. The more distant that past, the more dramatic the tension and the more interest the site holds.

There was, however, a change in perceptual mode. A traditional site such as the tomb of Su Xiaoxiao, which had long enjoyed pre-eminence, was losing its luster in the eyes of our visitors. Traditionally, educated tourists to West Lake routinely indulged in elegiac lamentations cued by such sites as the Su Xiaoxiao tomb; now they engaged in emotional exercises of a different sort or register. The change occurred at the level of moods. The taste for traditional effeminate delicacy now gave way to a newfound or revived fascination with a stalwart valiancy and a robust martial spirit. This mood swing resulted from the austere and uncompromising tenor of the political climate. By distilling their revolutionary spirit into landscape representations in various media, eminent educators such as Huang Yanpei helped invigorate the public perceptual mode.

Fig.25 Group Picture of Jiangxi Revolutionary Assembly. 1911. From PHRC: 128.

�

Sites and Stray Thoughts

The revival of West Lake in modern times in fact owes a great deal to late-Qing officials. The Taiping Rebellion in the nineteenth century had left the lakeshore in ruins. The condition began to improve only after the Qing military generals, who made their names during their pacifying campaigns against the peasant insurgents, set up their villas around the lake. These properties were in turn converted into memorial temples and shrines dedicated to them. Late Qing magnates and ranking officials followed suit by building villas and mansions alongside the lake. The local administration established the Engineering Bureau, which, equipped with steamboats, began to maintain the famous sites. The railroad between Shanghai and Hangzhou, built in 1909, further galvanized real estate development along the lakeshore (MST: 3; XXZ: 1: 2-3). With the overthrow of the Qing government, many of the buildings initially associated with Qing officials were

renamed to honor Ming loyalists who had anti-Qing reputations.

Huang's compositional scheme corroborates and reaffirms this revolutionary practice, as seen in his photographic representation of the Tuisheng Retreat 退省庵. The estate was initially the villa of Peng Yulin (1816-1890), a prominent Qing general. Upon his death, it was turned into a memorial temple dedicated to him (Zhao 1976-77: 87: 2606). After the 1911 Revolution it was converted into the Shrine of Former Worthies (Xianxian Ci 先賢祠), honoring three distinguished Chinese scholars of the Zhejiang region: two of them Ming loyalists who resisted the Qing invasion and one an eighteenth-century scholar who resigned from his official Qing government post to take up a hermit's life on West Lake.[29] The 1910 photograph album, focusing on the fantastic Nine Lion Rock in the pond outside the entrance to the temple, did not make the identity of the site too much of an issue [Fig.28]. Huang took two photographs of the site. Both compositions are expanded to include and highlight the gate of the shrine, with the overhead plaque identifying the site as Shrine of Former Worthies.[Fig.29]

Fig.26 Yo [Yue] Fei's tomb. Before 1910. From XHFJ: 31.

Fig.27 Huang Yanpei. Yoh Fei's [Yue Fei's] tomb; Entrance to Yoh Fei's [Yue Fei's] tomb. 1914. From ZMX 1:7,8.

�

Calling the estate Shrine of Former Martyrs, Gao Xie, the Southern Society member, strictly toed the line of political correctness, which we might expect for a Southern Society member. Chen Yilan, the Shanghai woman, who also visited the site on her tour, had a different view: she identified the estate as the former Tuisheng Retreat associated with the Qing general Peng Yulin 彭玉鱗. She acknowledged that the three Ming scholars, to whom the shrine was dedicated after the revolution, deserved the honor, for their wisdom, learning, and the unjust treatment they had received. Yet none of these political implications were on her mind when she loitered inside the estate. Instead, she experienced the site as what it was initially meant to be, a garden villa. She enjoyed the coolness and the elegance of this waterfront manor, an undisturbed world unto itself. She took time to savor the poetic couplets, most of them written by Peng himself. In particular, she liked the lines that best describe the place, such as:

Oak leaves, reed catkins, the autumn rustles in;

Idle clouds and deep pond, the sun glides by.

Or:

The floating life is like a dream, who does not inhabit it?

One finds home wherever one can settle in.

These lines made her think of Peng as a transcendental recluse. Apparently repulsed by the Republican attempt to erase Peng's association with this estate, she felt a 'fish bone in [her] throat [she] was dying to disgorge.' The Taiping peasant rebels, in her opinion, had wreaked havoc, and their leaders were 'blindly stupid' and 'meanly avaricious.' The Qing military generals who pacified the rebellion should be credited with sparing the country further catastrophes. For those generals with integrity like Peng, she says, there was no point in confiscating their property and estates. Moreover, she laments the fact that the new regime had poorly maintained the confiscated properties, some of which were falling into ruin. 'Just because it is a taboo subject,' Chen blurts out, 'does not mean that I should keep my mouth shut.' For this remark, she was teased by her uncle and called an 'arch-diehard' (XYH: 24: 4-5). Elsewhere on her tour, soon after her cursory visit to the Zhejiang Revolutionary Soldiers' memorial, Chen admired yet another couplet by Peng Yulin, which, she felt, had 'an unsurpassed profoundly poignant resonance' (XYH: 24: 15). Likewise, for Fang, the high school boy, political correctness was a moot issue. He roamed into a compound that was formerly the shrine of two prominent Qing generals, Jiang and Zhuo. Since the Revolution, the site had been converted for use by the Seal-Carving Society of West Coolness. The impressionable boy stumbled into a hall that still exhibited the portraits of the two Qing generals, where he found the image of one of them 'robust,' the other 'gallant,' both 'visibly spirited' (shenqi yiran 神氣奕然) (XYH: 25: 5).

Fig.28 The Nine-Lion Rock. Before 1910. From XHFJ: 13.

�

The revolutionary authorities and activists may have sought to map onto the landscape an opposition between a new Republican identity and an old Manchu imprint by adding new memorials and zealously changing names of sites. However, such a binary opposition did not sink in with our visitors, except the Suzhou scholar Gao Xie, who was the most politically conscious of the four. He was in tears on an earlier trip when he failed to find the Ming loyalist Zhang Cangshui's 張蒼水 tomb. Now with the tomb restored after the revolution (for obvious reasons of historical analogy), he was outraged to see that it still bore Qing imperial inscriptions (XYH: 23: 7). He was the only one of the four to visit the White Cloud Nunnery (Baiyun An 白雲庵),[30] the headquarters of the Zhejiang revolutionary party. There, a 'fierce-looking and wildly barking dog' greeted him and scared the daylights out of his friends, who immediately took flight (XYH: 23: 7).

Conclusion

Fig.29 Huang Yanpei. Temple of Great Men. From ZMX: 1:28.

�

The foregoing comparison between Huang's photographs and the four tourist travelogues of West Lake reveals areas of both agreement and disagreement. Out of this emerges a picture of the period perception of the 1910s that is more balanced and less biased than conventional representations. The physical landscape indeed had changed: new monuments were built and old temples of imperial connections were renamed and reappropriated for the Republican cause. This architectural change of identity on the lakeshore imbued the landscape with a moral overtone. Huang's photographs in many ways corroborate a n d affirm this change, thereby conveying the vision of a revolutionary activist. Such a change and its corresponding visual rhetoric as propagated by educators such as Huang through various media—not the least a mong them photography—apparently had their impact on the public perception of landscape, but in an abstract way. The revolution may have polarized the landscape somewhat along the line of binary oppositions (Qing vs. Republican, imperial vs. modern), but very few tourists would conscientiously follow, or care that much about, such a polarization. However, with the direction of public attention to new monuments and the revival of some traditional symbols with modern revolutionary resonances, a set of new values and perceptual categories hitherto largely unassociated with the West Lake landscape—such as 'sublime aura' and 'heroic spirit'—were being either absorbed, internalized, or reactivated in the public's perception of West Lake. At the same time, some of the old sites—such as the Su Xiaoxiao tomb—that were associated with values and moods at odds with the new, invigorating spirit seem to have lost their luster. The appearance of new architecture on the lakeshore was itself subject to further change. It was the changes in perceptual style that would have long-lasting effects and consequences.

Previous

Notes:

[14] From ZGMS: 3: 9. If we compare it with Huang's photograph of the same site, this photograph would appear to be the original one from the 1910 edition. Even though the new edition of the album changes the caption of the site to 'Public Park,' the photographic rhetoric remains hinged on its association with imperial eminence.

[15] The English caption omits the reference to the Qing temple, presumably because Zhuang Yu, the editor of vol. 3, did not consider it relevant to foreign visitors. It reads: 'The Memorial Hall of the Patriots (Soldiers Died in the First Revolution, 1910) and View in Front of the Public Garden.'

[16] For a sustained analogy of West Lake as a female beauty, see, for instance, a seventeenth-century example in You 1985: 149-150.

[17] Shen Fu (1763-1807?), a native of Suzhou, considers most of the scenes, in spite of their 'exquisite wonders', to exhibit nothing more than the 'overtones of rouge and powder' (zhifen qi 脂粉氣). See Shen 1993: 74.

[18] Yuan Daochong, an early twentieth-century scholar, observes that 'fans who praise West Lake always liken it to a female beauty; landscape architects consistently decorate it with flowers and trees, thus making West Lake into an effeminate landscape, woefully lacking in the sublime aura of masculine elan' (zhangfu angcang zhi

qixiang 丈夫昂藏之氣象) (1937: 69).

[19] Tao Qian, 'Drinking Wine V', translation by Stephen Owen (1996: 316).

[20] By the Qing period, the term was more frequently used in connection with architectural monuments in tower-climbing poems. The final definitive twist came from Wang Guowei, who praises Li Bo's description of the austere sight of Han ruins ('Memorial pillar-gates on Han mausoleums [buffeting] west wind [and bathed in] evening glow') as the ultimate embodiment of 'sublime aura' (1981: 6). For discussion of the term, see Lin 1983: 300-304; Owen 1992: 400-401.

[21] Both the Xihu zhi and Xihu xinzhi feature a section 'Graves and Tombs' (XXZ: 9: 1-1 0).

[22] The localization of the romance in the West Coolness Bridge may have resulted from a confusion between 'West Hill' (xiling 西陵) and 'West Coolness' (Xiling 西泠) (Lu 1981: 75-77).

[23] For Qiu Jin's statement made after she was arrested, see Peng 1941: 91-92.

[24] Tao Chenzang first suspected that the line might have, been fabricated by others. This is reiterated by Mary Rankin (1971: 187), who also suspects that the poem was actually made up by a sympathizer shortly after Qiu's death, even though she acknowledges that it 'hardly matters because its real importance was its propaganda effect.' More recent scholarship has yielded evidence that Qiu indeed composed the line. The evidence comes from the exchange of telegraphs between the Zhejiang governor and Qiu's persecutor, Gui Fu, who confirmed the existence of the seven characters of the line. See Zhou Feitang et al. 1981: 104; Zheng/Chen 1986: 181.

[25] See Yang/Wang 1995: 83. In the same year Qiu died, Gao Xie contributed to the inaugural issue of Shenzhou Women's Newspaper, which published a collection of works mourning Qiu's death. See Yang/Wang 1995: 93.

[26] There was a conscious use of the pun: 'mourning Qiu' (bei Qiu 悲秋) and 'mourning autumn' (bei qiu 悲秋). See Yang/Wang 1995: 102.

[27] In the early Qing, someone dug up a stone stela allegedly bearing the inscription: 'Tomb of Wu Song' thereby inspiring the rumors (XXZ: 9: 4b-Sa; Shen Tuqi 1982: 70-71).

[28] For Wu Luzhen's revolutionary career, see Hu Zushun 1949: 8-9; Zhang Guogan 1958: 197-202; Zhu Yanjia 1960: 6: 161-232; Wright 1968: 384-385, 426-427.

[29] They are Huang Zongxi (1610-1659), Lü Liuliang (1629-1683), Hang Shijun (1696-1773). See Cao 1985: 92, fn.7.

[30] Chen Yilan, the Shanghai woman, noted that her uncle and her brother did visit the White Cloud Nunnery, which apparently did not attract her. All she cared about was to get from her uncle a report on a poetic couplet displayed there (XVH: 24: 19).

Bibliography:

Baxandall, Michael. 1980. The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cao Wenqu 曹文趣, et al., eds. 1985. Xihu youji xuan 西湖遊記選 (Selected travelogues of West Lake). Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi.

Chen Xingzhen 陳杏珍. 1977. 'Leifengta de mingcheng ji qita' 雷峰塔的名稱及其他 (The name of the Thunder Peak Pagoda and other issues). Wenwu tiandi 6: 40-44.

Chesneaux, Jean, et al. 1979. China from the 1911 Revolution to Liberation. Tr. P. Auster and L. Davis. New York: Pantheon Books.

Dillon, E. J. 1911. 'The Most Momentous Event for 1000 Years.' Contemporary Review (December): 874.

Hu Zushun 胡祖舜. 1949. Wuchang kaiguo shilu 武昌開國史錄 (Record of the founding of the Republic at Wuchang). Wuchang: Jiuhua yinshuguan.

Huang Yanpei 黃炎培. 1914. 'Preface' of West Lake, Hangchow, vol. 1. In ZGMS.

———. 1934. Zhidong (Heading east). Shanghai: Shenghuo.

Jiang Weiqiao 蔣維喬. 1959. 'The Commericial Press and Zhonghua Press in their early phase'. In Zhang Jing l u 張靜廬, ed., Zhongguo xiandai chuban shiliao 中國現代出版史料 (Materials of history of modern Chinese publishing business). Shanghai: Zhonghua, ser. no. 4, 2: 396-399.

Li Tinghan 李廷翰. 1920. 'You Hang ji' 遊杭記 (Touring Hangzhou). In XYH 1920:11-12.

Lin, Shuen-fu. 1983. 'Chiang K'uei's Treatises on Poetry and Calligraphy'. In Susan Bush and Christian F. Murck, eds., Theories of the Arts in China. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lu Ciyun 陸次雲. 1999. Huru zaji 湖*雜記. In Xu Fengji 徐逢吉, Qingbo xiaozhi wai bazhong 清波小志外八種 (Notes on Clear Waves and eight other works) Eds. Shi Diandong 施奠東 et al. Shanghai: Shanghai guji.

Lu Jiansan 陸鑒三, ed. 1981 . Xihu bicong 西湖筆叢 (Writings on West Lake). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Lu Yi 陸詒. 1999. 'Shi Liangcai yu Shenbao' 史量才與申報 (Shi Liangcai and Shenbao). In Lu Jianxin 陸堅心 et al., eds., 20 shiji Shanghai wenshi ziliao wenku 20世紀上海文史資料文庫 (Collection of cultural historical materials of 20th century Shanghai). Shanghai: Shanghai, 6: 1-8.

Miyazaki Noriko. 1984. 'Saiko o meguru kaiga—Nan So kaigashi sho tanichi' (Paintings of West Lake: preliminary exploration of history of painting of Southern Song). In Umehara Kaoru, ed., Chugoku kinsei no toshi to bunka (Urban culture of early modern China). Kyoto: Kyoto daigaku bunjin kagaku kenkyujo, 209-237.

MST. Mingshan tu 名山圖. 1994. In Zhongguo gudai banhua congkan erbian 中國古代版畫叢刊二遍. Shanghai: Shanghai guji. vol. 8. First edition 1633.

Owen, Stephen. 1986. Remembrances: The Experience of the Past in Classical Chinese Literature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

——. 1992. Readings in Chinese Literary Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

——, ed./tr. 1996. Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York and London: vii. W. Norton.

Peng Ziyi 彭子儀 ed. 1941 . Qiu Jin 秋瑾. Shanghai: Yaxin.

A Pictorial History of the Republic of China—Its Founding and Development. 1981. 2 vols. Taipei: Modern China Press.

Price, Don C. 1990. 'Constitutional Alternatives and Democracy in the Revolution of 1911.' In Ideas Across Cultures: Essays on Chinese Thought in Honor of Benjamin I. Schwartz. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, Council on East Asian Studies. 223-260.

Qian Yueyou 潛説友. 1983-1986. Xianchun Linan zhi 咸淳臨安志 (Gazetteer of Lin'an compiled during the Xianchun period). In Yingyin Wenyuange siku quanshu 景印文淵閣四庫全書. 1500 vols. Taipei: Taiwan shangwu, vol. 490.

Rankin, Mary B. 1968. 'The Revolutionary Movement in Chekiang: A Study in t h e Tenacity of Tradition.' In Rankin, China in Revolution: The First Phase 1900-1913. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 354-355.

——. 1971. Early Chinese Revolutionaries: Radical Intellectuals in Shanghai and Chekiang, 1902-1911. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schrecker, John E. 1991. The Chinese Revolution in Historical Perspective. New York: Greenwood Press.

Shen Fu 沈復. 1993. Fusheng liuji 浮生六記 (Six chapters from a floating life). Beijing: Shumu wenxian.

Shen Tuqi 沈屠奇. 1982. Xihu gujin tan 西湖古今談 (Notes on West Lake, past and present). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Spence, Jonathan D. 1981. The Gate of Heavenly Peace: The Chinese and Their Revolution, 1895-1980. New York: Penguin Books.

Strassberg, Richard E., tr. 1994. Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Tian Rucheng 田汝成. 1980. Xihu youlanzhi 西湖遊覽志 (A travel guide to West Lake). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Wang, Eugene Y. 2003. 'Trope and Topos: the Leifeng Pagoda and the Discourse of the Demonic.' In Judith Zeitlin and Lydia Liu, eds., Materializing Writing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wang Guowei 王國維. 1981. Renjian cihua xinzhu 人間詞話新註 (New annotated lyric meter poetics from the human world). Jinan: Qilu shushe.

Wang Huabin 王華斌. 1992. Huang Yanpei zhuan 黃炎培傳 (Biography of Huang Yanpei). Jinan: Shandong wenyi.

Wang Lu 王露 et al., comp. 1934. Zhejiang tongzhi 浙江通志 (Gazetteer of Zhejiang). Shanghai: The Commercial Press. First edition 1736.

Wright, Mary C. 1968. China in Revolution: the First Phase, 1900-1913. New Haven: Yale University Press.

XHFJ. 1926. Xihu fengjing 西湖風景 (Views of West Lake). Shanghai: Commercial Press. First edition in 1910.

XHZ. 1735. Xihu zhi 西湖志 (Gazetteer o f West Lake). 48 juan. Comp. Wang Lu 王露. Hangzhou: Zhejiang shuju.

XXZ. 1921 . Xihu xin zhi 西湖新志 (New gazetteer of West Lake). Ed. Hu Xianghan. 胡祥翰. N .p.

XYH. 1920. Xin youji huikan 新遊記匯刊 (A collection of new travelogues). Shanghai: Zhonghua.

Xu Hansan 許漢三. 1985. Huang Yanpei nianpu 黃炎培年譜 (Huang Yanpei: a chronology). Beijing: Wens hiziliao.

Yang Tianshi 楊天石 and Wang Xuezhuang 王學莊, comps. 1995. Nanshe shi changbian 南社史長編 (Annals of South Society). Beijing: Zhongguo renmin.

Yang Yi 楊義, et al. 1997. Zhongguo xinwenxue tuzhi 中國新文學圖志 (Illustrated history of new Chinese literature). Beijing: Renmin wenxue.

Yao Wenzhan 姚文栴. 1921. 'Preface.' In XXZ: 4b.

Ye Guangting 葉光庭 and Lü Yichun 呂以春. 1982. Xihu manhua 西湖漫話 (Miscellaneous notes on West Lake). Tianjin: Tianjin renmin.

You Tong 尤侗. 1985. 'Liuqiao qiliu ji' 六橋泣柳記 (Mourning the lost willows on the Six-Bridge embankment). In Cao 1985: 149-151.

Young, Ernest P. 1977. The Presidency of Yuan Shih-k'ai: Liberalism and Dictatorship in Early Republican China. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Yuan Daochong 袁道沖. 1937. 'Hubin jiuying' 湖濱舊影 (Old reflections of lakeshore). Yuefeng Supplement 1. Rpt. in Cao 1985: 62-69.

Zhang Guogan 張國淦. 1958. Xinhai geming shiliao 辛亥革命史料 (Historical materials on the 1911 Revolution). Shanghai: Longmen lianhe.

Zhang Renmei 張任美. 1985. 'Xihu jiyou' 西湖記遊 (Note on touring West Lake). In Cao 1985: 37-42.

Zhao Erxun 趙爾巽, et. al., comps. 1976-1977. Qing shigao 清史稿 (Draft history of the Qing). Beijing: Zhonghua.

Zheng Yunshan 鄭雲山 and Chen Dehe 陳德禾. 1986. Qiu Jin pingzhuan 秋瑾評傳(Critical biography of Qiu Jin). Kaifeng: Henan jiaoyu.

Zhou Feitang 周芾棠, et al., eds. 1981. Qiu Jin shiliao 秋瑾史料 (Historical materials on Qiu Jin). Changsha: Hunan renmin.

Zhou Feng 周峰, ed. 1992. Minguo shiqi Hangzhou 民國時期杭州 (Hangzhou in the Republican period). Hangzhou: Zhejiang renmin.

Zhu Yanjia 朱炎佳. 1960. 'Wu Luzhen yu Xinhai geming' 吳祿貞與辛亥革命 (Wu Luzhen and the Chinese Revolution). In Wu Xiangxiang 吳相湘, ed., Zhongguo xiandaishi congkan 中國現代史叢刊 (Selected writings on modern Chinese history). Taipei: Zhengzhong.

ZGMS. Zhongguo mingsheng 4: Xihu 中國名勝西湖 (Scenic China series no. 4: West Lake, Hangchow) . Eds. Huang Yanpei 黃炎培, et al. 3 vols. Shanghai: The Commercial Press.

|